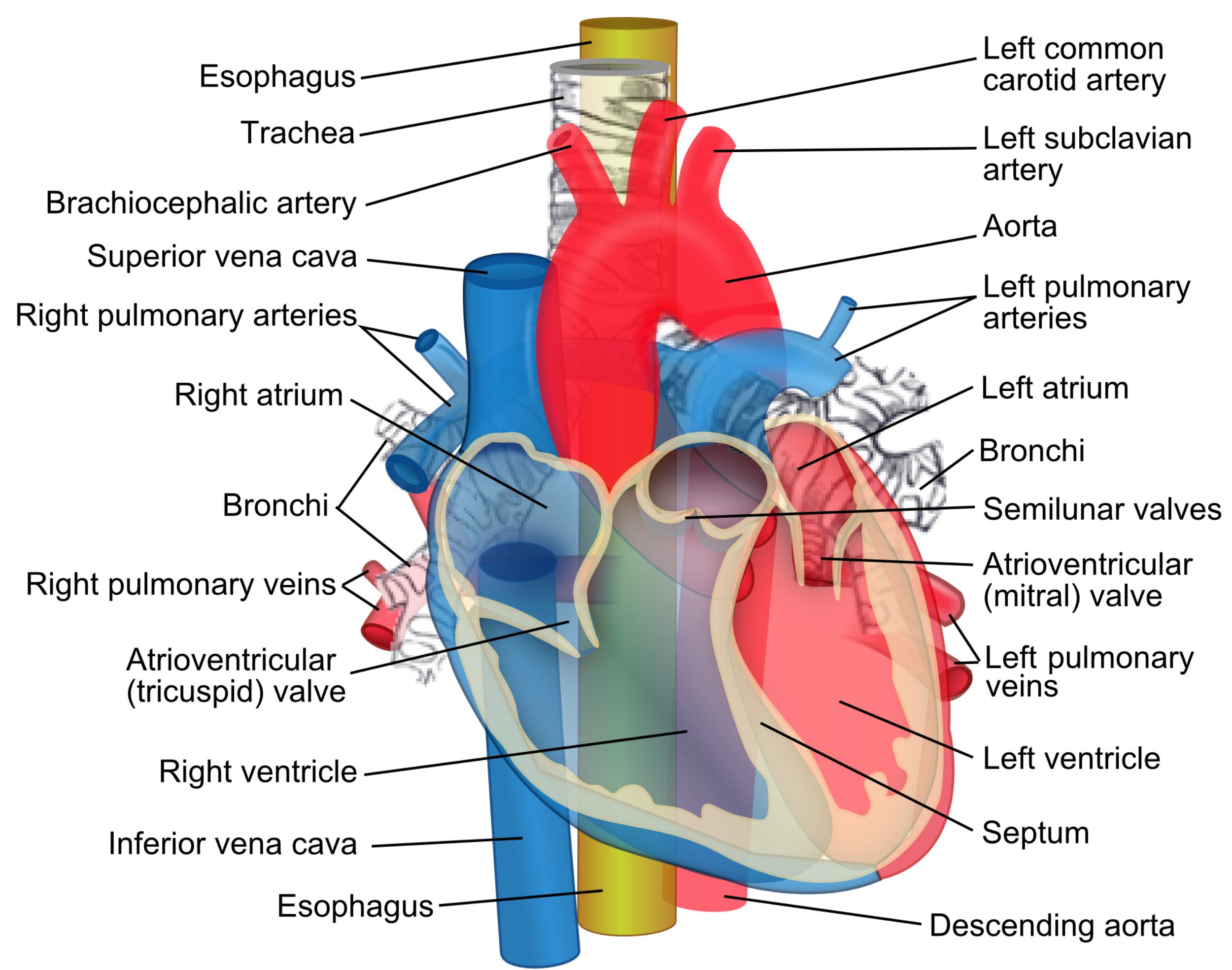

The ascending aorta represents the vital beginning of the systemic arterial system, emerging from the heart’s left ventricle to carry oxygenated blood to the entire body. This complex region of the mediastinum involves intricate relationships between the heart, major vessels, and the respiratory structures of the chest. Understanding the anterior view of these components is essential for diagnosing cardiovascular conditions and planning thoracic surgical interventions.

Esophagus: The esophagus is a muscular tube that facilitates the transport of food and liquids from the pharynx to the stomach. It is positioned posteriorly to the trachea and the heart, running through the length of the thoracic cavity.

Trachea: The trachea serves as the primary airway for the respiratory system, leading from the larynx toward the lungs. It is structurally reinforced by C-shaped cartilaginous rings that prevent it from collapsing during pressure changes.

Brachiocephalic artery: Also referred to as the innominate artery, this is the first and largest branch arising from the aortic arch. It eventually bifurcates into the right common carotid and right subclavian arteries.

Superior vena cava: This large, thin-walled vein is responsible for returning deoxygenated blood from the upper body to the right atrium. It sits to the right of the ascending aorta and is formed by the confluence of the brachiocephalic veins.

Right pulmonary arteries: These vessels branch off the pulmonary trunk to carry deoxygenated blood into the right lung for gas exchange. They pass behind the ascending aorta and the superior vena cava to reach the pulmonary hilum.

Right atrium: The right atrium is the receiving chamber for deoxygenated blood returning from the systemic circulation via the venae cavae. It contracts to move blood through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle.

Bronchi: The bronchi are the main respiratory passages that branch from the trachea to enter each lung. They continue to divide into smaller bronchioles, providing a path for air to reach the alveoli.

Right pulmonary veins: These veins are unique because they carry oxygen-rich blood from the right lung back to the left atrium. Typically, there are two right pulmonary veins that enter the posterior aspect of the heart.

Atrioventricular (tricuspid) valve: This valve is located between the right atrium and the right ventricle, consisting of three distinct leaflets. Its primary role is to prevent the backflow of blood into the atrium during right ventricular contraction.

Right ventricle: The right ventricle is a muscular chamber that pumps deoxygenated blood into the pulmonary circulation via the pulmonary valve. Its walls are significantly thinner than the left ventricle’s because it pumps against lower resistance.

Inferior vena cava: As the largest vein in the human body, the inferior vena cava returns deoxygenated blood from the lower extremities and abdomen. It enters the heart at the lower part of the right atrium.

Left common carotid artery: This vessel is the second major branch of the aortic arch, supplying oxygenated blood to the left side of the head and neck. It is a critical component for maintaining stable cerebral blood flow.

Left subclavian artery: Originating as the third branch of the aortic arch, this artery provides the main blood supply to the left upper limb. It also gives off branches that supply the vertebral column and thoracic wall.

Aorta: The aorta is the primary and largest artery in the body, originating directly from the left ventricle. It follows a curved path, initially ascending before arching over the heart to become the descending aorta.

Left pulmonary arteries: These arteries transport deoxygenated blood from the heart to the left lung. They are located inferiorly to the aortic arch and anteriorly to the left primary bronchus.

Left atrium: The left atrium receives oxygenated blood from all four pulmonary veins. During atrial contraction, it pushes blood through the mitral valve into the left ventricle.

Semilunar valves: This term refers to the aortic and pulmonary valves, which are located at the base of the great arteries. They prevent blood from leaking back into the heart chambers after it has been ejected.

Atrioventricular (mitral) valve: Also known as the bicuspid valve, it is situated between the left atrium and left ventricle. It ensures that blood flows in a single direction from the receiving chamber to the main pumping chamber.

Left pulmonary veins: These vessels bring freshly oxygenated blood from the left lung to the left atrium. Efficient flow through these veins is essential for maintaining cardiac output.

Left ventricle: The left ventricle is the most muscular chamber of the heart, responsible for pumping blood through the entire systemic circuit. It generates high pressure during ventricular systole to propel blood into the aorta.

Septum: The interventricular septum is the thick wall of muscle that separates the right and left ventricles. It prevents the mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood within the heart.

Descending aorta: This is the continuation of the aorta after it passes the arch, traveling downward through the thorax and abdomen. It provides blood to the lower half of the body through various smaller arterial branches.

The thoracic cavity houses the body’s most critical life-support systems, organized in a way that maximizes efficiency and protection. At the center of this organization is the heart, which serves as a dual-pump system for both pulmonary and systemic circulation. The ascending aorta acts as the gateway for oxygenated blood, while the venae cavae serve as the return conduits for deoxygenated blood.

Surrounding the cardiovascular structures are the trachea and esophagus, which provide the essential pathways for air and nutrients. The relationship between these organs is highly compact, with the aorta arching over the left primary bronchus and the esophagus running directly behind the heart. This proximity is why certain cardiovascular conditions, such as an aortic aneurysm, can sometimes manifest as respiratory or swallowing difficulties.

Key anatomical and physiological landmarks include:

- The aortic root, which contains the aortic valve and the origins of the coronary arteries.

- The superior mediastinum, where the great vessels branch off to supply the head and arms.

- The bifurcation of the trachea (carina), which occurs near the level of the aortic arch.

- The pulmonary trunk, which sits anteriorly to the aorta at its origin.

The Hemodynamics of the Aorta and Heart Valves

The heart operates through a series of coordinated pressure changes that ensure blood moves forward. During diastole, the atrioventricular valves open to allow the ventricles to fill, while the semilunar valves remain tightly closed. As the heart enters systole, the pressure within the ventricles rises sharply, forcing the mitral and tricuspid valves shut and the aortic and pulmonary valves open. This cycle is the foundation of human hemodynamics, allowing the aorta to receive a surge of blood with every beat.

The elastic nature of the ascending aorta is particularly important for this process. It expands to accommodate the stroke volume of the left ventricle and then recoils, helping to maintain blood pressure and continuous flow during the resting phase of the heart. If the aorta becomes stiff or diseased, this buffering capacity is lost, often leading to hypertension and increased strain on the heart muscle.

Integration of the Pulmonary and Systemic Circuits

The diagram illustrates how the heart bridges the two primary circulatory paths. The right side of the heart handles the pulmonary circulation, sending blood to the lungs to pick up oxygen and release carbon dioxide. Once oxygenated, the blood returns to the left side of the heart, where it is pressurized and sent into the systemic circulation via the aorta. This separation is maintained by the septum, which is critical for ensuring that the blood delivered to the tissues has the highest possible oxygen saturation.

Clinically, the anterior view of these structures is the perspective most commonly used in imaging studies like chest X-rays and CT scans. Medical professionals use these visual landmarks to assess heart size, check for fluid in the lungs, or identify blockages in the major arteries. By understanding the normal course of the ascending aorta and its surrounding structures, clinicians can more accurately identify life-threatening anomalies and provide timely treatment.

The intricate design of the thoracic organs demonstrates the remarkable synergy between the cardiovascular and respiratory systems. From the robust walls of the left ventricle to the flexible rings of the trachea, every component is specialized to facilitate life. A thorough knowledge of this anatomy remains the cornerstone of modern medicine, providing the clarity needed to navigate the complexities of human health and disease.