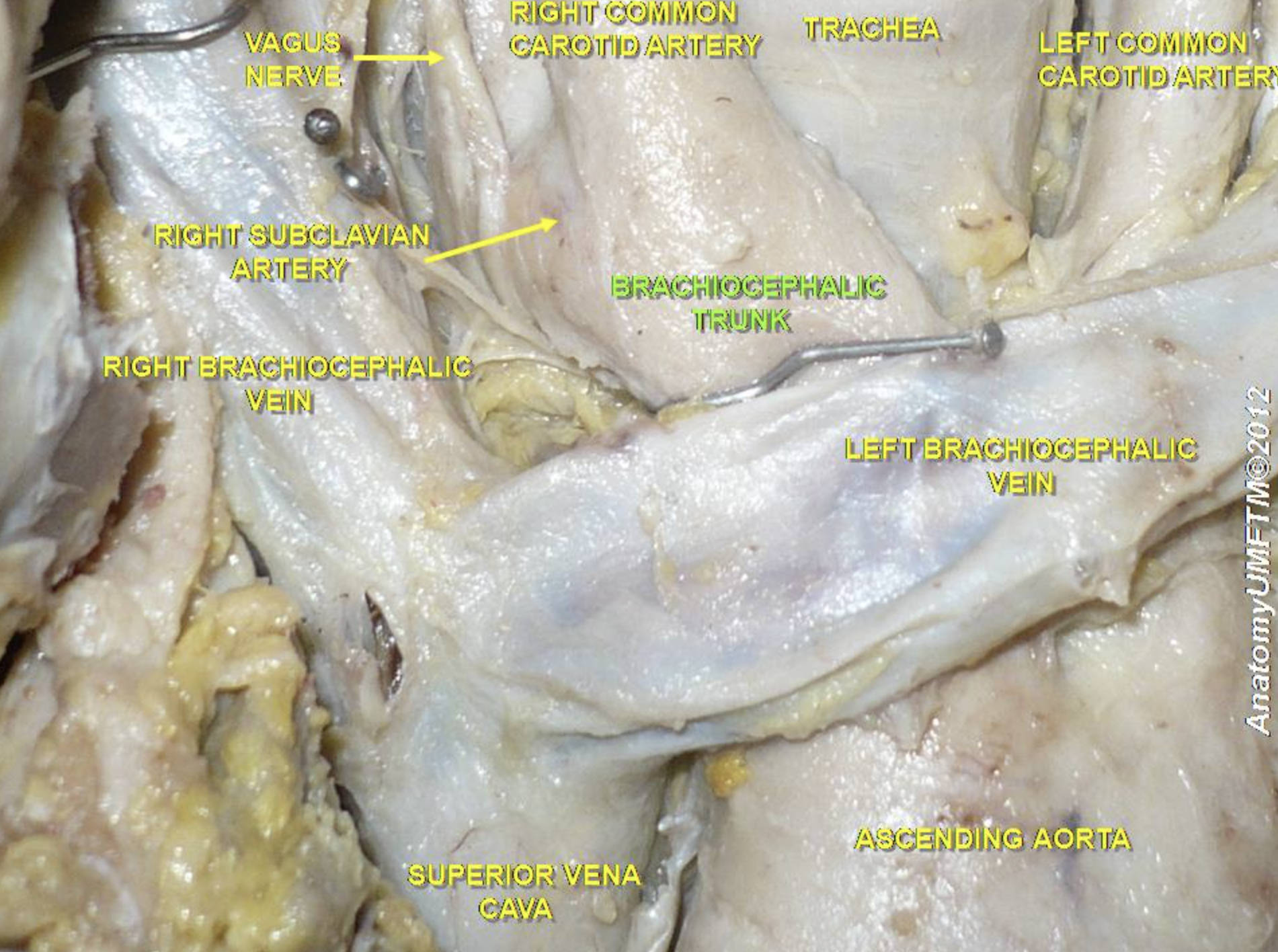

This detailed cadaveric dissection highlights the complex vascular architecture of the superior mediastinum, specifically focusing on the brachiocephalic trunk and the surrounding great vessels. The image provides a clear, anterior view of the major arterial and venous pathways responsible for transporting blood between the heart, the head, the neck, and the upper limbs, serving as an essential reference for understanding thoracic anatomy and surgical planning.

Vagus Nerve: This is the tenth cranial nerve (CN X), visible here descending through the neck into the thorax. It plays a critical role in the autonomic nervous system, providing parasympathetic innervation to the heart, lungs, and digestive tract to regulate heart rate and peristalsis.

Right Subclavian Artery: This major artery branches off the brachiocephalic trunk and arches outward toward the right arm. It is responsible for supplying oxygenated blood to the right upper limb, as well as parts of the neck and brain via its branches, such as the vertebral artery.

Right Brachiocephalic Vein: This vein is formed by the union of the right internal jugular vein and the right subclavian vein. It descends vertically to join the left brachiocephalic vein, contributing to the formation of the superior vena cava.

Right Common Carotid Artery: Arising from the bifurcation of the brachiocephalic trunk, this vessel ascends into the neck. It is the primary supplier of oxygenated blood to the right side of the head and brain, eventually splitting into internal and external carotid arteries.

Brachiocephalic Trunk: Also known as the innominate artery, this is the first and largest branch of the aortic arch. It is a unique structure found only on the right side of the body, where it ascends briefly before dividing into the right common carotid and right subclavian arteries.

Vagus Nerve (arrow pointing right): The label indicates the continued path of the vagus nerve as it travels near the carotid sheath. Its close proximity to the major arteries makes it a vital structure to identify and protect during surgeries involving the mediastinum or neck.

Trachea: Commonly known as the windpipe, the trachea is a cartilaginous tube located centrally in the image. It serves as the main airway, conducting air from the larynx down to the bronchi and lungs, and is structurally supported by C-shaped cartilage rings.

Left Common Carotid Artery: Unlike its counterpart on the right, this artery typically arises directly from the aortic arch. It ascends along the left side of the trachea to supply blood to the left side of the head and brain.

Left Brachiocephalic Vein: This vein is significantly longer than the right brachiocephalic vein because it must cross from the left side of the body to the right to reach the superior vena cava. It drains blood from the left upper limb and left side of the head and neck.

Ascending Aorta: This large vessel emerges from the left ventricle of the heart and carries high-pressure oxygenated blood. It curves to form the aortic arch, from which the brachiocephalic trunk, left common carotid, and left subclavian arteries originate.

Superior Vena Cava: This large diameter vein is formed by the confluence of the right and left brachiocephalic veins. It returns deoxygenated blood from the upper half of the body directly to the right atrium of the heart.

The Architecture of the Superior Mediastinum

The anatomical region depicted in this dissection is the superior mediastinum, a crowded and clinically vital compartment located within the thoracic cavity between the lungs. This area serves as a “grand central station” for the body’s vascular and respiratory systems. It houses the Great Vessels, which are the large arteries and veins that carry blood to and from the heart. The spatial arrangement here is critical; the rigid trachea sits centrally, flanked by high-pressure arteries and low-pressure veins, all packed tightly behind the manubrium of the sternum.

A key feature of human anatomy shown here is the asymmetry of the arterial supply. On the right side, the aorta does not branch directly into the carotid and subclavian arteries. Instead, it produces the brachiocephalic trunk (innominate artery). This single trunk acts as a shared stem that eventually splits. Conversely, on the left side, the common carotid and subclavian arteries usually branch directly and independently from the aortic arch. This asymmetry is a fundamental concept for students and surgeons, as variations in this pattern can have significant clinical implications.

The venous system in this region also displays distinct characteristics designed to accommodate the body’s shape. While the arteries pump blood away from the heart under high pressure, the veins return blood passively. The left brachiocephalic vein is notably longer and more oblique than the right because the superior vena cava sits on the right side of the midline. Therefore, blood from the left side of the head and arm must travel across the chest to reach the heart.

Key anatomical relationships in this region include:

- Anterior-Posterior Arrangement: The veins (brachiocephalic and superior vena cava) generally lie anterior to the arteries (aortic arch branches), which in turn lie anterior to the trachea.

- Neurovascular Proximity: Nerves such as the vagus and phrenic nerves run parallel to these large vessels.

- Lymphatic Drainage: The thoracic duct, the body’s main lymphatic vessel, also traverses this area, usually draining near the junction of the left internal jugular and subclavian veins.

Physiology of Mediastinal Hemodynamics

The structures visible in this cadaveric specimen are responsible for systemic circulation to the upper body. The ascending aorta receives the full force of the left ventricular contraction. The elasticity of the aortic wall allows it to expand during systole (heart contraction) and recoil during diastole (heart relaxation), a mechanism known as the Windkessel effect. This ensures that blood flow through the branches, such as the brachiocephalic trunk, remains relatively smooth and continuous rather than stopping completely between heartbeats.

The venous return system, anchored by the Superior Vena Cava, operates under much lower pressure. Because there is no pump pushing blood back to the heart from the veins, this system relies on pressure gradients and the respiratory pump. When a person inhales, the pressure in the thoracic cavity decreases, helping to draw blood from the head and arms through the brachiocephalic veins and into the right atrium. Any obstruction in this area, such as a tumor compressing the superior vena cava, can lead to a condition called Superior Vena Cava Syndrome, causing swelling and fluid retention in the upper body.

Clinical Relevance of the Great Vessels

Understanding the precise layout of these vessels is paramount for various medical procedures. For instance, central venous catheters are often inserted into the internal jugular or subclavian veins. Clinicians must navigate these catheters into the superior vena cava without puncturing the adjacent arteries or damaging the nearby lung apex. The image clearly demonstrates why the right side is often preferred for certain procedures; the vertical path of the right internal jugular vein into the right brachiocephalic vein and straight down to the heart is a more direct route than the tortuous path from the left.

Furthermore, the proximity of the vagus nerve to the carotid and subclavian arteries highlights the risks associated with neck and thoracic surgeries. Damage to the vagus nerve can result in vocal cord paralysis (via its recurrent laryngeal branch) or issues with autonomic regulation. This dissection serves as a reminder of the intricate and delicate nature of the Superior Mediastinum, where millimeter differences in position separate vital life-support structures.

In conclusion, this image offers a foundational view of the upper thoracic anatomy. By identifying the brachiocephalic trunk, its branches, and the venous tributaries, medical professionals gain the spatial awareness necessary for diagnosis and intervention. The interplay between the respiratory tract, the arterial supply, and the venous drainage in this confined space is a testament to the efficiency of human biological design.