Differential staining is a cornerstone technique in clinical microbiology, allowing laboratory professionals to distinguish between various types of bacteria based on their chemical and structural properties. By utilizing specific dyes and protocols, these methods provide critical information regarding cell wall composition, virulence factors, and morphological structures, which is essential for accurate disease diagnosis and treatment planning.

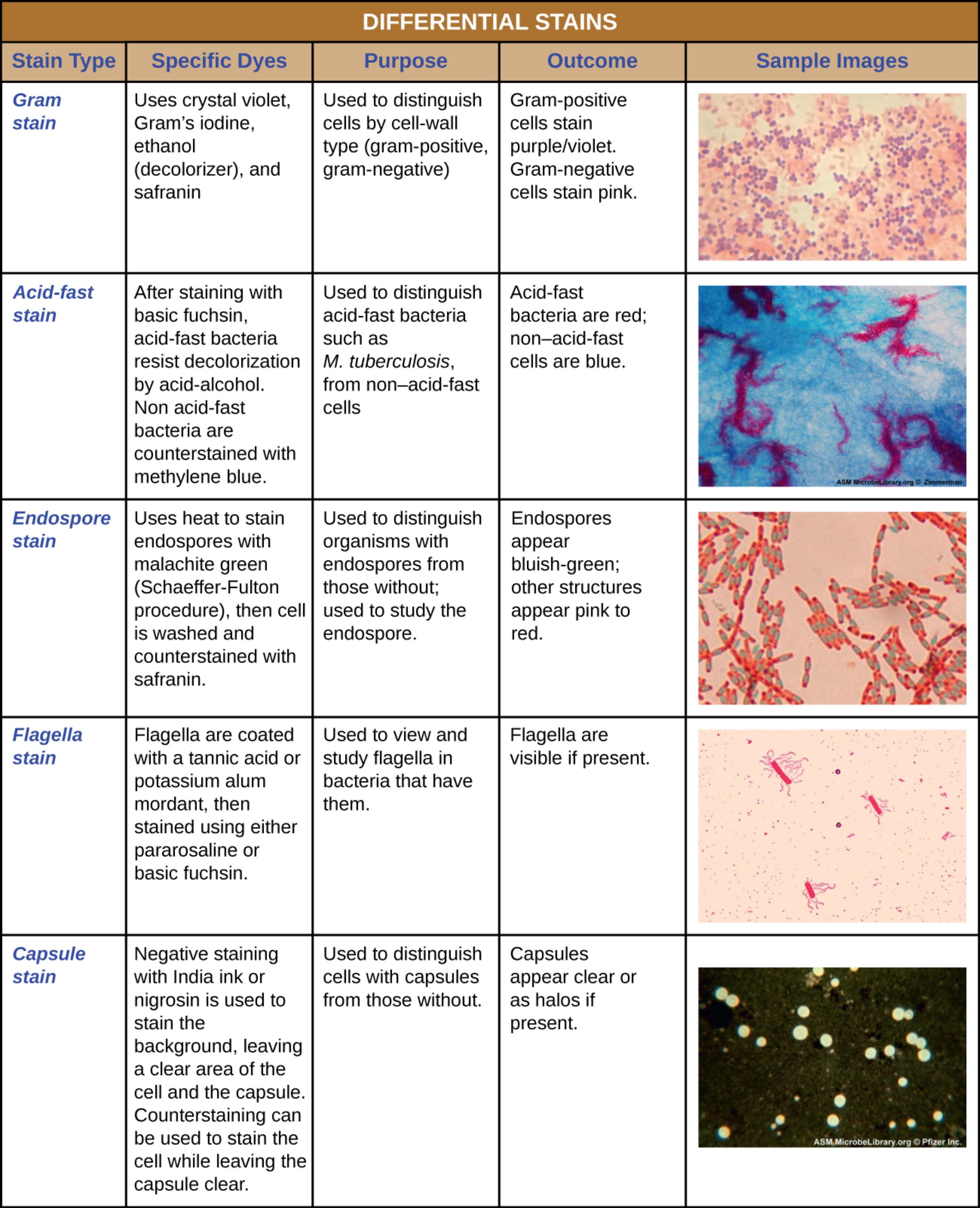

Gram stain: This fundamental technique uses crystal violet, Gram’s iodine, ethanol, and safranin to categorize bacteria based on the thickness of their peptidoglycan cell wall. The outcome distinguishes Gram-positive cells, which appear purple or violet, from Gram-negative cells, which appear pink.

Acid-fast stain: This method involves staining with basic fuchsin followed by an acid-alcohol wash to identify bacteria with high mycolic acid content in their cell walls. In this process, acid-fast bacteria retain the red dye, while non-acid-fast cells are decolorized and counterstained blue with methylene blue.

Endospore stain: This technique utilizes heat to force malachite green dye into resistant, dormant structures known as endospores. The result is a distinct contrast where the endospores appear bluish-green, and the surrounding vegetative bacterial cells are counterstained pink to red.

Flagella stain: Because bacterial flagella are too thin to be seen with standard optics, this stain coats them with a mordant like tannic acid or potassium alum to increase their diameter. Once coated and stained with pararosaniline or basic fuchsin, the flagella become visible, aiding in the identification of motile bacteria.

Capsule stain: This differential method employs a negative staining technique using India ink or nigrosin to darken the background rather than the cell itself. The outcome highlights the bacterial capsule as a clear halo surrounding the cell, which distinguishes encapsulated pathogens from those without this virulence factor.

The Role of Differential Staining in Disease Diagnosis

Differential stains are far more complex and informative than simple stains, which merely reveal cell shape and arrangement. These techniques rely on the chemical and physical differences between bacterial species to produce varying visual results. In a clinical setting, the ability to rapidly categorize bacteria is vital for initiating appropriate patient care. For example, knowing whether an organism is Gram-positive or Gram-negative helps physicians choose the correct empirical antibiotic, as these two groups differ significantly in their susceptibility to various drugs.

These staining procedures also reveal structural adaptations that contribute to bacterial virulence—the ability of an organism to cause disease. Structures such as capsules protect bacteria from being engulfed by the host’s immune system, while flagella allow pathogens to swim toward nutrients or invade tissues. Endospores represent a survival mechanism that allows certain bacteria to withstand extreme environmental stress, making them difficult to eradicate from hospitals.

Key clinical applications of differential staining include:

- Rapid Identification: Providing immediate clues about the causative agent of an infection before culture results are available.

- Virulence Assessment: Detecting protective structures like capsules or spores that indicate a more resilient pathogen.

- Treatment Guidance: narrowing down antibiotic choices based on cell wall properties (e.g., Gram stain results).

- Quality Control: verifying the purity of laboratory cultures.

One of the most critical applications of differential staining is the diagnosis of Tuberculosis (TB). As noted in the image, the acid-fast stain is specifically designed to identify organisms like Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This bacterium possesses a unique cell wall rich in mycolic acid, a waxy substance that repels most standard dyes, including the Gram stain. TB is a contagious airborne disease that primarily attacks the lungs, though it can affect other parts of the body. Symptoms often include a persistent cough, chest pain, unintended weight loss, and night sweats. Because the waxy barrier of the bacterium makes it resistant to drying and disinfectants, early detection via acid-fast staining is crucial for public health to prevent transmission and begin the lengthy course of antibiotics required for a cure.

Conclusion

Mastering differential staining techniques is essential for any medical laboratory professional. These methods provide the initial roadmap for identifying pathogens, revealing not just who the bacteria are, but also what protective or locomotive tools they possess. From the ubiquity of the Gram stain to the specialized application of the acid-fast stain for detecting tuberculosis, these visual diagnostic tools remain a primary line of defense in the fight against infectious diseases.