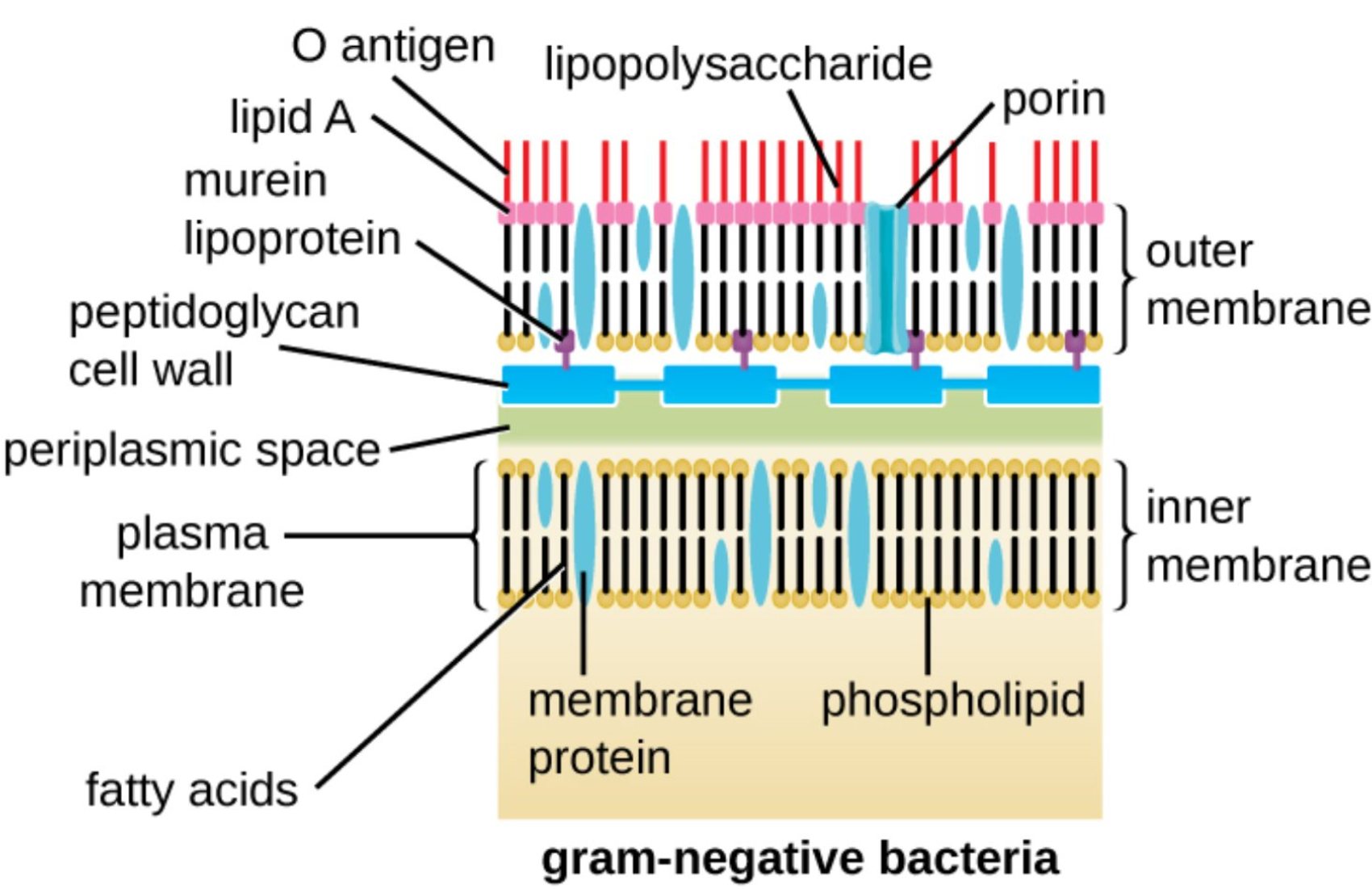

The Gram-negative bacterial cell wall is a sophisticated, multi-layered envelope that provides both structural integrity and a specialized chemical barrier against environmental stressors. Featuring a dual-membrane system with a thin intermediary peptidoglycan layer, this anatomical arrangement is a primary factor in the survival and virulence of numerous pathogenic species. Understanding these microscopic structures is essential for medical research, particularly in the development of treatments for drug-resistant infections.

O antigen: This is the outermost polysaccharide chain of the lipopolysaccharide molecule that extends into the surrounding medium. It serves as a major surface antigen used by the host’s immune system for identification and can vary significantly between different bacterial strains.

lipid A: This hydrophobic portion anchors the lipopolysaccharide to the outer membrane and is the primary source of endotoxin activity. When released during bacterial cell death, it can trigger intense immune responses in humans, potentially leading to fever, inflammation, and toxic shock.

murein lipoprotein: Also known as Braun’s lipoprotein, this molecule covalently links the thin peptidoglycan layer to the outer membrane. It provides essential structural cohesion, ensuring that the entire cell envelope remains a stable and unified protective barrier.

peptidoglycan cell wall: In Gram-negative bacteria, this layer is relatively thin but remains crucial for maintaining the cell’s mechanical strength. It acts as a scaffold that prevents the bacterium from bursting due to internal osmotic pressure generated by the high concentration of solutes in the cytoplasm.

periplasmic space: This is the gel-like compartment located between the inner and outer membranes of the cell. It houses a variety of proteins and enzymes involved in nutrient transport, cell wall synthesis, and the degradation of potentially toxic substances before they enter the cell.

plasma membrane: Also known as the inner membrane, this selectively permeable bilayer directly surrounds the bacterial cytoplasm. It is the site of vital metabolic functions, including the generation of the proton motive force required for the synthesis of ATP.

fatty acids: These hydrophobic hydrocarbon chains form the internal core of the phospholipid bilayers in both the inner and outer membranes. Their specific composition and length determine the fluidity and permeability characteristics of the bacterial boundaries.

lipopolysaccharide: Commonly referred to as LPS, this large molecule is a unique and defining component of the Gram-negative outer membrane. It consists of Lipid A, a core oligosaccharide, and the O antigen, contributing significantly to the cell’s defense against chemical attacks.

porin: These are channel-forming proteins embedded in the outer membrane that facilitate the passive diffusion of small hydrophilic molecules. They are critical for the uptake of essential nutrients but can also limit the entry of larger antibiotic molecules into the cell.

outer membrane: This second lipid bilayer is found only in Gram-negative bacteria and serves as an additional layer of physiological protection. It contains specialized lipids and proteins that distinguish it chemically and functionally from the inner cytoplasmic membrane.

inner membrane: This is the primary phospholipid bilayer that encloses the cell’s internal contents and maintains the electrochemical gradient. It regulates the movement of ions and molecules and contains various integral proteins necessary for cellular respiration.

membrane protein: These are diverse proteins located within or on the surface of the lipid bilayers throughout the cell envelope. They perform essential tasks such as signal transduction, active transport of solutes, and maintaining the overall structural integrity of the bacterial wall.

phospholipid: These are the fundamental lipid components that spontaneously form bilayers in aqueous environments to create cellular boundaries. Each molecule consists of a hydrophilic phosphate head and hydrophobic fatty acid tails, creating a barrier that is impermeable to most polar substances.

Functional Significance of the Gram-Negative Envelope

The Gram-negative bacterial cell wall is a marvel of biological engineering, presenting a much more complex arrangement than its Gram-positive counterparts. This structure is defined by its characteristic “sandwich” appearance, where a thin layer of peptidoglycan is situated between two distinct lipid bilayers. This dual-membrane system is not merely for structural support; it serves as a highly specialized filter that controls the passage of nutrients and toxic substances.

The outer membrane is perhaps the most significant feature from a medical perspective. It serves as a formidable shield that protects the underlying peptidoglycan and inner membrane from chemical threats, including detergents, bile salts, and many antibiotics. Within this outer leaflet lies lipopolysaccharide, a molecule that plays a dual role as both a protective layer for the bacterium and a potent trigger for the human immune response during an infection.

Key anatomical features of the Gram-negative envelope include:

- An asymmetric outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharides and porins.

- A periplasmic space that acts as a reaction chamber for metabolic enzymes.

- A thin, cross-linked peptidoglycan layer providing essential structural rigidity.

- A selectively permeable inner membrane that manages the cell’s electrochemical gradient.

This anatomical complexity has profound implications for pathogenicity and how we treat bacterial diseases. Because Gram-negative bacteria have an extra layer of defense, they are often naturally resistant to antibiotics that easily penetrate the thick, exposed peptidoglycan of Gram-positive organisms. Understanding the specific molecular gates, such as porins, is essential for developing the next generation of antimicrobial agents.

Physiological Defense and Molecular Gates

The physiological resilience of Gram-negative bacteria is rooted in the unique chemistry of their outer membrane. Unlike the inner membrane, which is a standard phospholipid bilayer, the outer membrane is asymmetric. The outer leaflet is composed primarily of lipopolysaccharides, which create a dense, hydrophilic barrier. This barrier is highly effective at excluding hydrophobic molecules, making these bacteria difficult to target with conventional lipophilic drugs.

To overcome the barrier imposed by the outer membrane, the bacteria utilize specialized channels known as porins. These proteins form aqueous pores that allow for the selective permeability of small hydrophilic molecules like glucose and amino acids. However, the size and charge of these pores can be a limiting factor. Many bacteria can alter their porin expression as a defensive mechanism to prevent the entry of antibiotics, leading to significant challenges in modern clinical medicine.

Beneath the outer membrane lies the periplasm, a dynamic environment that contains high concentrations of proteins and enzymes. It serves as a crucial area for defense; many Gram-negative bacteria secrete enzymes into the periplasm, such as beta-lactamases, which can degrade antibiotics before they ever reach their target. This localized defense mechanism is a major contributor to the global rise of antibiotic resistance.

In summary, the Gram-negative bacterial cell wall represents a sophisticated multi-layered defense system that is central to the survival and virulence of many pathogens. From the toxicological impact of Lipid A to the selective filtering provided by porins, every component plays a specific role in maintaining cellular homeostasis while interacting with the host environment. By unraveling the complexities of this anatomical structure, medical science can continue to find new ways to bypass these microbial defenses and treat even the most stubborn infections.