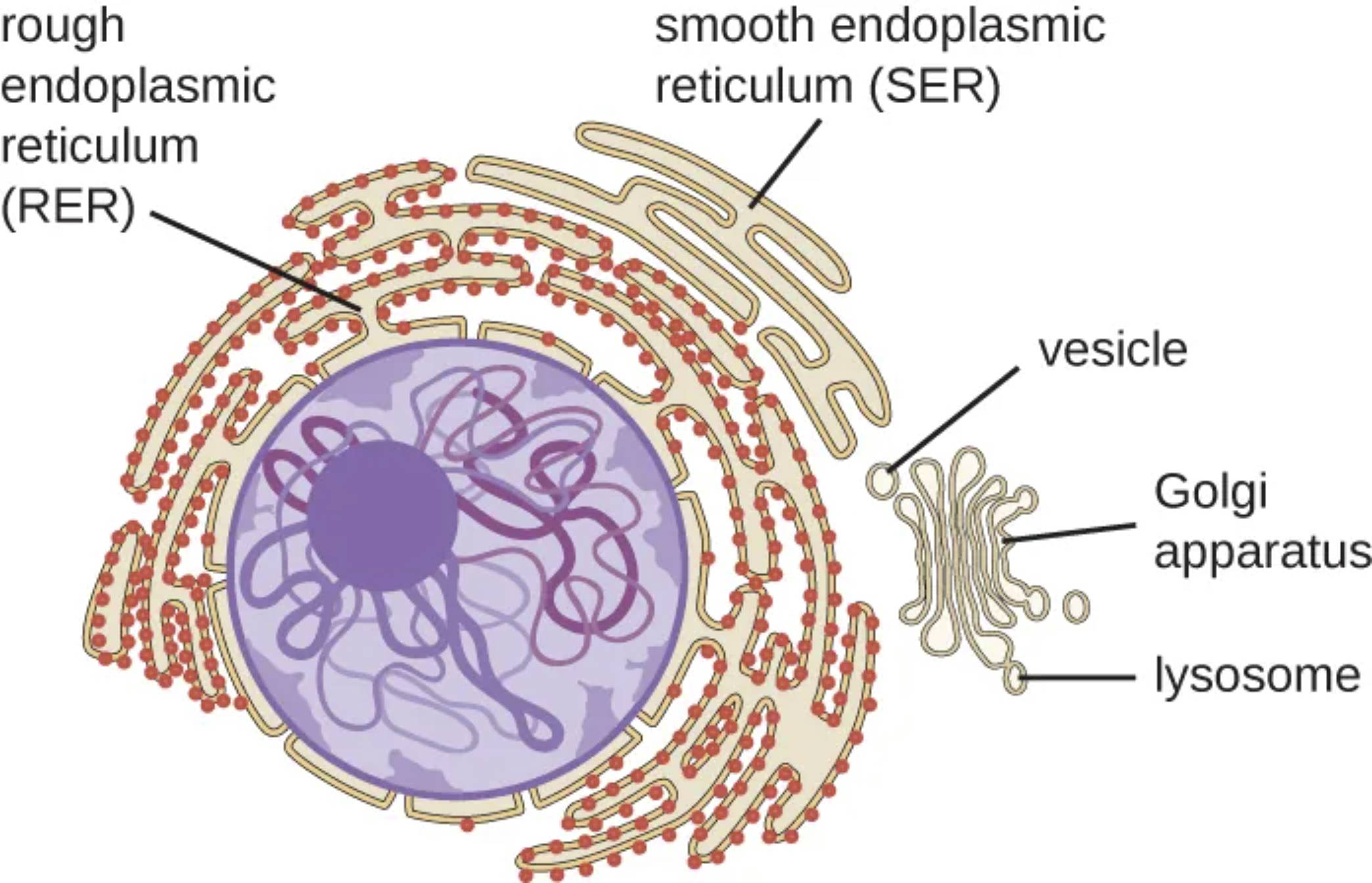

The endomembrane system is an intricate group of membranes and organelles in eukaryotic cells that work together to modify, package, and transport lipids and proteins. This system ensures that cellular products reach their intended destinations, whether inside the cell or secreted into the extracellular environment, maintaining physiological homeostasis.

rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER): This organelle is characterized by the presence of ribosomes on its surface, giving it a granular appearance under a microscope. It is primarily responsible for the synthesis of proteins that are destined for secretion or insertion into cellular membranes.

smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER): Unlike the RER, this structure lacks ribosomes and is involved in the synthesis of essential lipids, phospholipids, and steroids. It also plays a vital role in metabolizing carbohydrates and detoxifying various poisons or drugs within the cell.

vesicle: These are small, membrane-bound sacs that function as transport vehicles for moving materials between different components of the endomembrane system. They bud off from one organelle and fuse with another, ensuring that cargo is delivered safely and efficiently.

Golgi apparatus: Often described as the shipping and receiving center of the cell, this organelle consists of flattened membranous sacs called cisternae. It modifies products coming from the ER, such as glycoproteins, and sorts them before they are dispatched to their final locations via new vesicles.

lysosome: These specialized vesicles contain hydrolytic enzymes designed to break down macromolecules like proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. They are essential for intracellular digestion and for recycling damaged organelles through a process known as autophagy.

The Marvel of Cellular Engineering

The endomembrane system represents a masterclass in biological logistics, functioning as a coordinated network that spans from the nucleus to the cell membrane. It includes the nuclear envelope, the endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and various types of vesicles. Together, these structures create a specialized internal environment that allows the cell to compartmentalize biochemical reactions, ensuring that destructive enzymes are contained while essential proteins are synthesized and shipped.

One of the most critical aspects of this system is its dynamic nature. Membranes are constantly flowing and transforming as vesicles bud off from the ER and fuse with the Golgi apparatus. This “membrane flow” allows the cell to rapidly adjust its output based on physiological needs, such as when a pancreatic cell must suddenly increase insulin production in response to blood sugar spikes.

Components of the endomembrane system include:

- The nuclear envelope, which protects the genetic material and is continuous with the ER.

- The Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), which serves as the primary manufacturing site for proteins and lipids.

- The Golgi Apparatus, acting as the central distribution hub for sorting cargo.

- Lysosomes and Peroxisomes, which manage waste processing and cellular detoxification.

- The Plasma Membrane, which regulates the final exit of materials into the body.

The continuity of these membranes, either through physical connections or vesicle transport, is what defines the system. By segregating different metabolic processes, the cell avoids biochemical interference and can maintain the high level of organization necessary for complex life.

Intracellular Transport and Manufacturing

The intracellular transport within the endomembrane system follows a highly regulated pathway that begins in the RER. Here, newly synthesized polypeptides are folded into their three-dimensional shapes. Often, these proteins undergo glycosylation, where carbohydrate chains are added, preparing them for their eventual roles as receptors or signaling molecules on the cell surface.

Once the cargo is ready, the ER packages it into transport vesicles that travel to the “cis” face of the Golgi apparatus. Within the Golgi cisternae, more complex modifications occur, such as the addition of phosphate groups or the remodeling of sugar chains. These modifications serve as molecular “zip codes,” telling the cell exactly where the product belongs—whether it is a lysosomal enzyme meant to stay inside or a hormone meant to be released via exocytosis.

The physiological role of the SER is equally impressive, particularly in organs like the liver. In these tissues, the SER is loaded with enzymes that can modify toxic substances, making them more water-soluble so they can be easily excreted from the body. Furthermore, the SER is the primary site for the storage of calcium ions, which are crucial signaling molecules in muscle contraction and nervous system communication.

Cellular Health and Waste Management

Finally, the system ensures cellular health through the action of lysosomes. These organelles maintain an acidic internal pH that is optimal for their digestive enzymes. By breaking down foreign substances, such as bacteria engulfed by white blood cells, or worn-out cellular parts, the endomembrane system acts as a sophisticated recycling plant. This ensures that the cell’s raw materials are conserved and that potential pathogens are neutralized before they can cause damage.

The endomembrane system is a fundamental pillar of eukaryotic life, providing the structural and functional framework necessary for cellular complexity. By integrating synthesis, modification, and transport, it allows cells to communicate with their environment and maintain internal order. Understanding this system is crucial for appreciating the microscopic mechanisms that sustain human health and vitality every day.