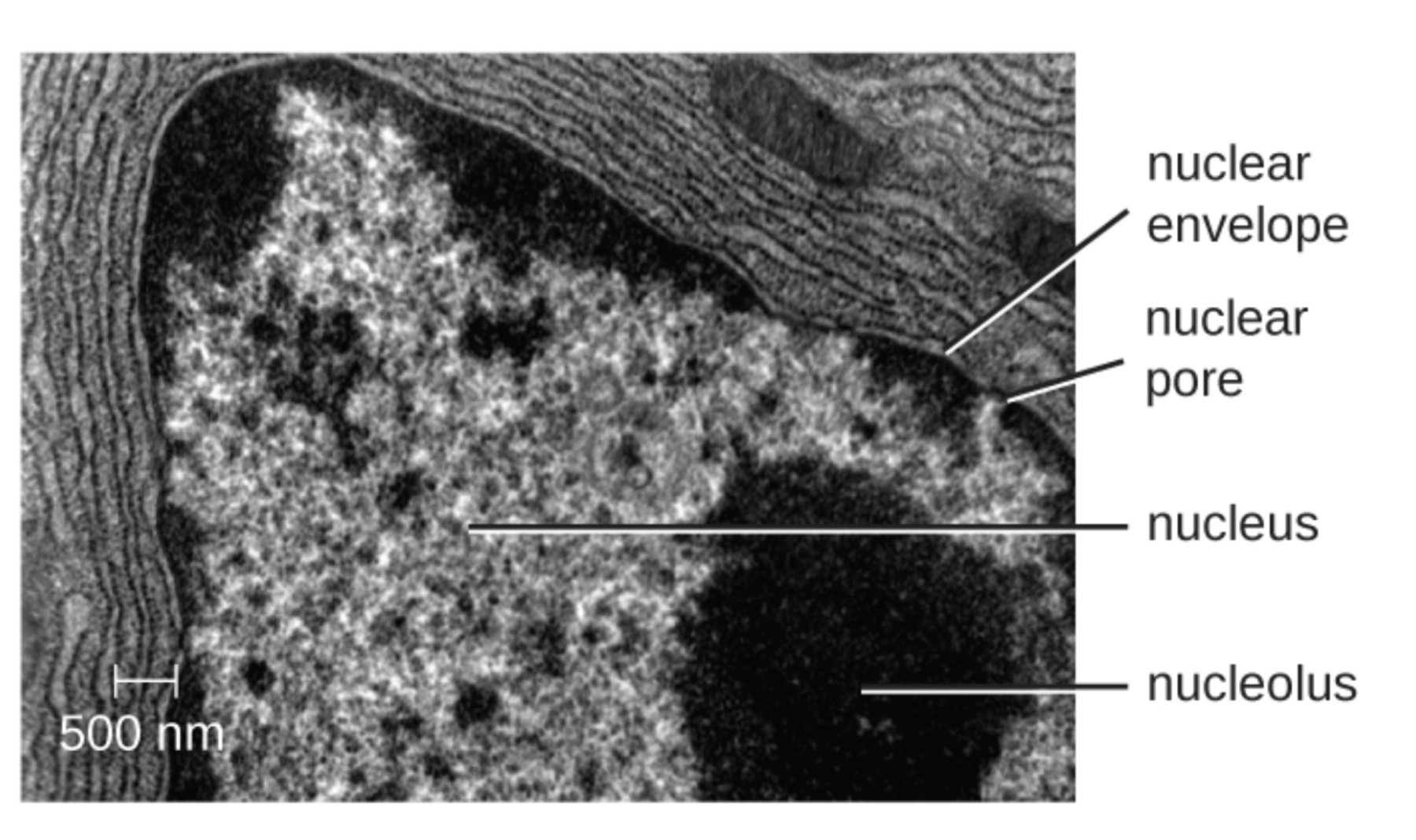

This transmission electron micrograph (TEM) offers a high-resolution view of the eukaryotic cell nucleus, revealing the intricate structures responsible for genetic storage and protein synthesis. Understanding the relationship between the nucleolus, nuclear envelope, and pores is essential for grasping how cellular communication and metabolic regulation occur at the microscopic level.

nuclear envelope: This double-membrane structure serves as the primary barrier between the genetic material and the cytoplasm. It provides structural integrity to the nucleus and protects DNA from metabolic reactions occurring in the rest of the cell.

nuclear pore: These are specialized protein channels that span the double membrane, allowing for the selective transport of macromolecules. They are critical for the export of messenger RNA and the import of nuclear proteins, maintaining the cell’s homeostatic balance.

nucleus: This organelle functions as the control center of the cell, housing the majority of the organism’s genetic information in the form of chromatin. It coordinates essential biological processes such as growth, metabolism, and reproduction through the regulation of gene expression.

nucleolus: Appearing as a prominent, electron-dense region within the nucleus, this structure is the site of ribosomal RNA synthesis. It orchestrates the assembly of ribosomal subunits, which are later transported to the cytoplasm to begin protein translation.

The Microscopic Architecture of the Genetic Hub

Transmission electron microscopy provides unprecedented detail into the ultrastructure of cellular organelles, allowing researchers to visualize components that are invisible under traditional light microscopy. In this particular image, with a scale bar of 500 nm, we can observe the nucleus as a dense, complex territory packed with genetic material. The dark, grainy regions throughout the nucleus represent chromatin in various stages of condensation, reflecting the cell’s current transcriptional activity.

The nucleolus stands out as the most prominent feature within the nuclear interior. Unlike many other organelles, it is not bound by a membrane, allowing it to act as a dynamic biochemical hub. It is often referred to as a “ribosome factory” because its primary physiological role is to produce the components necessary for protein synthesis. This activity is so intense that it creates the dense, dark appearance seen in the electron micrograph, as it is saturated with RNA and associated proteins.

The nuclear complex performs several vital functions to maintain cellular homeostasis:

- The regulation of gene expression by controlling which sections of DNA are accessible for transcription.

- The synthesis and processing of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) within the nucleolar regions.

- The selective transport of proteins and nucleic acids through specialized pore complexes.

- The physical separation of the sensitive transcription process from the translation machinery in the cytoplasm.

Physiological Processes of the Nucleolus and Nuclear Envelope

From a physiological standpoint, the nucleolus is organized around specific chromosomal regions known as nucleolar organizer regions (NORs). These regions contain the genes for rRNA, which are transcribed at incredibly high rates. Once the rRNA is synthesized, it undergoes complex folding and is joined by ribosomal proteins that have been imported from the cytoplasm. This assembly results in the formation of the 40S and 60S subunits, which must then be exported back through the nuclear pores to form functional ribosomes.

The nuclear envelope, clearly visible as the dark border surrounding the nucleus, is not a simple wall but a sophisticated gatekeeper. It consists of two lipid bilayer membranes—the inner and outer nuclear membranes—separated by a thin space. The outer membrane is continuous with the rough endoplasmic reticulum, which can be seen in the surrounding cytoplasm as layered, ribosome-studded sheets. This connection ensures that the instructions for protein synthesis can be efficiently communicated from the nucleus to the cell’s manufacturing centers.

The nuclear pore complexes are perhaps the most complex protein structures in the cell. Each pore is composed of approximately 30 different proteins called nucleoporins. These pores are capable of moving thousands of molecules per second, yet they remain highly selective. Small molecules can diffuse freely, but larger proteins and RNA strands require specific transport receptors to pass through. This gating mechanism prevents genomic instability by ensuring that only the correct enzymes and signals reach the DNA.

The study of nuclear ultrastructure is fundamental to modern medicine, as disruptions in these components are linked to numerous conditions, including certain types of cancer and progeria (premature aging). By visualizing these structures through electron microscopy, scientists can better understand how cells maintain their health and how therapeutic interventions might target cellular malfunctions at the most basic level.