The processes of mitosis and meiosis represent two fundamental mechanisms of eukaryotic cell division, each serving distinct biological purposes. While mitosis is responsible for somatic cell growth and tissue repair by producing identical diploid daughter cells, meiosis facilitates sexual reproduction through the creation of genetically unique haploid gametes. Understanding these pathways is essential for grasping the complexities of human development, hereditary genetics, and reproductive medicine.

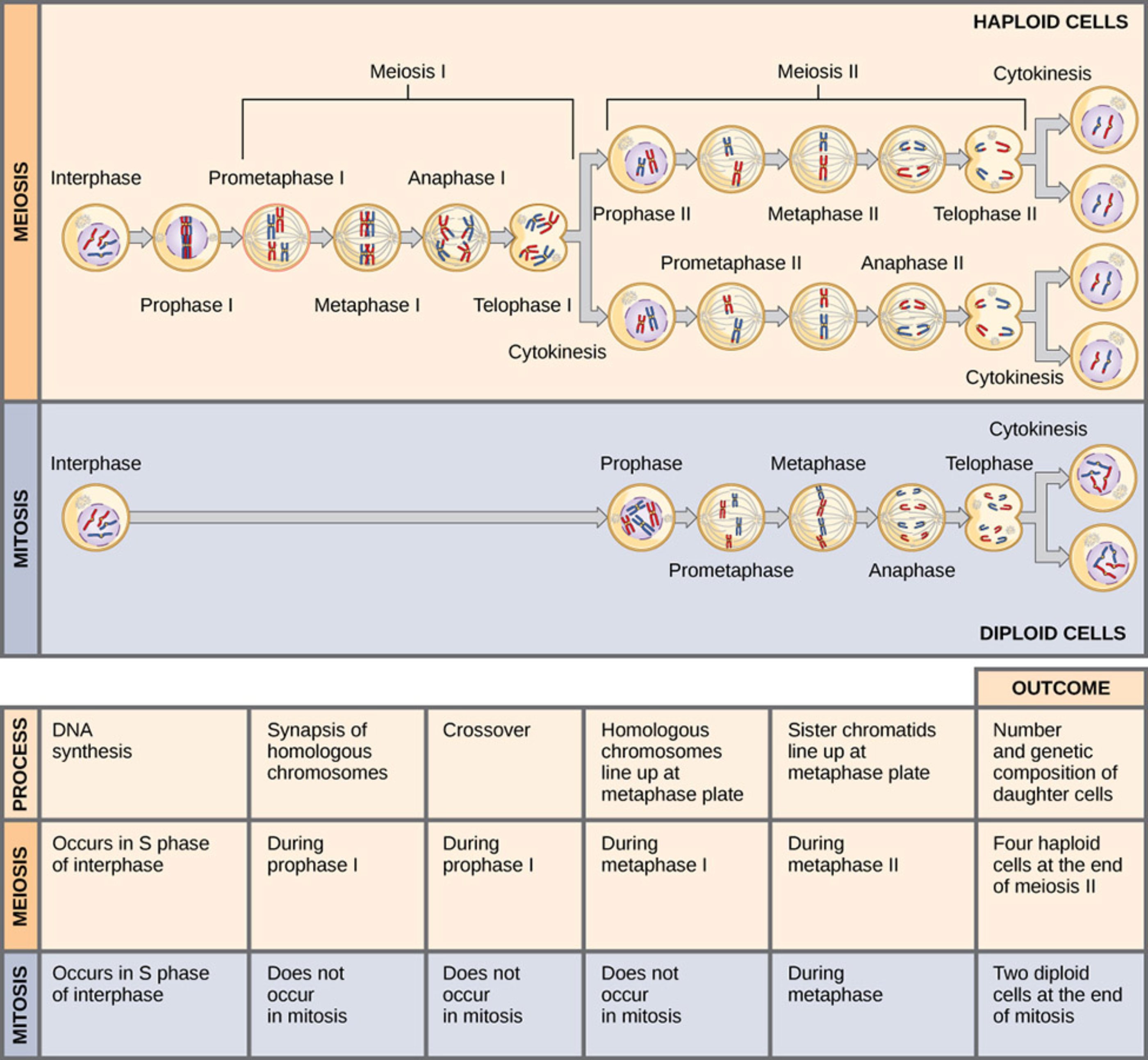

Interphase: This is the preparatory phase preceding both mitosis and meiosis where DNA synthesis occurs during the S phase. It ensures that the cell has a complete copy of its genome before starting the process of nuclear division.

Meiosis I: This first of two divisions in meiosis involves the separation of homologous chromosomes, effectively reducing the chromosome count by half. It includes critical events such as synapsis and crossing over, which contribute to genetic diversity.

Meiosis II: Often resembling a mitotic division, this second stage of meiosis involves the separation of sister chromatids within the haploid cells created in the previous step. The end result is four genetically distinct haploid daughter cells.

Mitosis: This process involves a single nuclear division that results in two daughter cells that are genetically identical to the parent cell. It is the primary method for growth, development, and tissue replacement in multicellular organisms.

Cytokinesis: This is the final physical division of the cytoplasm that occurs after nuclear division is complete. It results in the separation of the parent cell into two or four individual daughter cells, depending on whether mitosis or meiosis occurred.

Prophase I: A complex stage in meiosis where homologous chromosomes pair up and exchange genetic material. This process, known as crossing over, is a major source of genetic variation in offspring.

Haploid Cells: These are the final products of meiosis, containing only one set of chromosomes. In humans, these cells function as gametes (sperm and eggs) for sexual reproduction.

Diploid Cells: These cells contain two complete sets of chromosomes, one from each parent, and are the typical result of mitotic division. They make up the vast majority of somatic tissues in the human body.

Synapsis of homologous chromosomes: This unique event occurs only during prophase I of meiosis, where matching chromosomes from each parent pair up closely. This alignment is necessary for the subsequent exchange of genetic segments.

Crossover: Also occurring during prophase I, this process involves the physical exchange of DNA between non-sister chromatids of homologous pairs. It ensures that every gamete produced contains a unique combination of maternal and paternal genes.

Metaphase Plate: This is the imaginary plane at the center of the cell where chromosomes align before being separated. The way chromosomes align—either individually or in homologous pairs—determines the genetic outcome of the division.

The Architecture of Cellular Growth and Reproduction

The survival and reproduction of complex life forms depend on the precise execution of cellular division. Mitosis and meiosis are the two primary pathways through which cells replicate their genetic blueprints and partition them into new cellular units. While both processes share similar stages, their physiological outcomes are vastly different, dictated by the specific needs of the organism. Mitosis maintains the ploidy level of somatic cells, ensuring that tissues like the skin or liver remain functional through constant renewal.

In contrast, meiosis is a specialized form of division restricted to the germline. It involves two successive rounds of nuclear division following a single round of DNA replication. This “reduction division” is crucial for sexual reproduction, as it produces haploid gametes that combine during fertilization to restore the diploid state. Without the genetic shuffling that occurs during meiosis, biological diversity would be severely limited, and species would be less resilient to environmental changes.

The regulation of these cycles is a masterpiece of cellular engineering. Checkpoints throughout the process monitor the integrity of DNA and the alignment of chromosomes to prevent errors that could lead to developmental disorders or cellular malfunctions. By understanding the mechanical differences between these two paths, we can better comprehend the foundations of heredity and the biological basis for human life.

Notable distinctions between these cellular pathways include:

- The number of daughter cells produced (two vs. four).

- The genetic composition of the progeny (identical vs. unique).

- The occurrence of genetic recombination (absent in mitosis, present in meiosis).

- The specific tissue types where each process occurs (somatic vs. germline).

Anatomical and Physiological Contrasts

The anatomical differences between mitosis and meiosis are most apparent during the first stage of division. In mitosis, chromosomes line up individually at the metaphase plate, ensuring that each daughter cell receives an identical set of chromatids. This high-fidelity replication is the bedrock of anatomical stability, allowing the body to heal wounds and grow from an embryo into an adult while maintaining a consistent genetic identity across billions of cells.

Physiologically, meiosis introduces complexity through the pairing of homologous chromosomes. During prophase I, the synaptonemal complex facilitates the physical link between maternal and paternal chromosomes, allowing for the exchange of genetic material. This recombination is what makes every individual (except identical twins) genetically unique. This process is not just a biological curiosity; it is a vital evolutionary strategy that provides a pool of genetic variation for natural selection to act upon.

Furthermore, the outcome of these processes has significant implications for reproductive health. If meiosis fails to properly segregate chromosomes—a phenomenon known as nondisjunction—the resulting gametes may have an abnormal chromosome count. This can lead to chromosomal disorders such as Down syndrome or Turner syndrome. Conversely, malfunctions in mitotic regulation are a hallmark of oncogenesis, where cells bypass natural growth limits to form tumors. Thus, the study of these division cycles is a cornerstone of modern oncology and medical genetics.

The delicate balance between mitosis and meiosis defines the lifecycle of all eukaryotic organisms. While one provides the stability needed for an individual to thrive and repair itself, the other provides the variation needed for the species to evolve. As medical technology advances, our ability to monitor and influence these processes at the molecular level continues to grow, offering new pathways for treating genetic diseases and improving reproductive outcomes. Mastering the nuances of these cellular divisions remains one of the most important objectives in the field of biological and medical sciences.