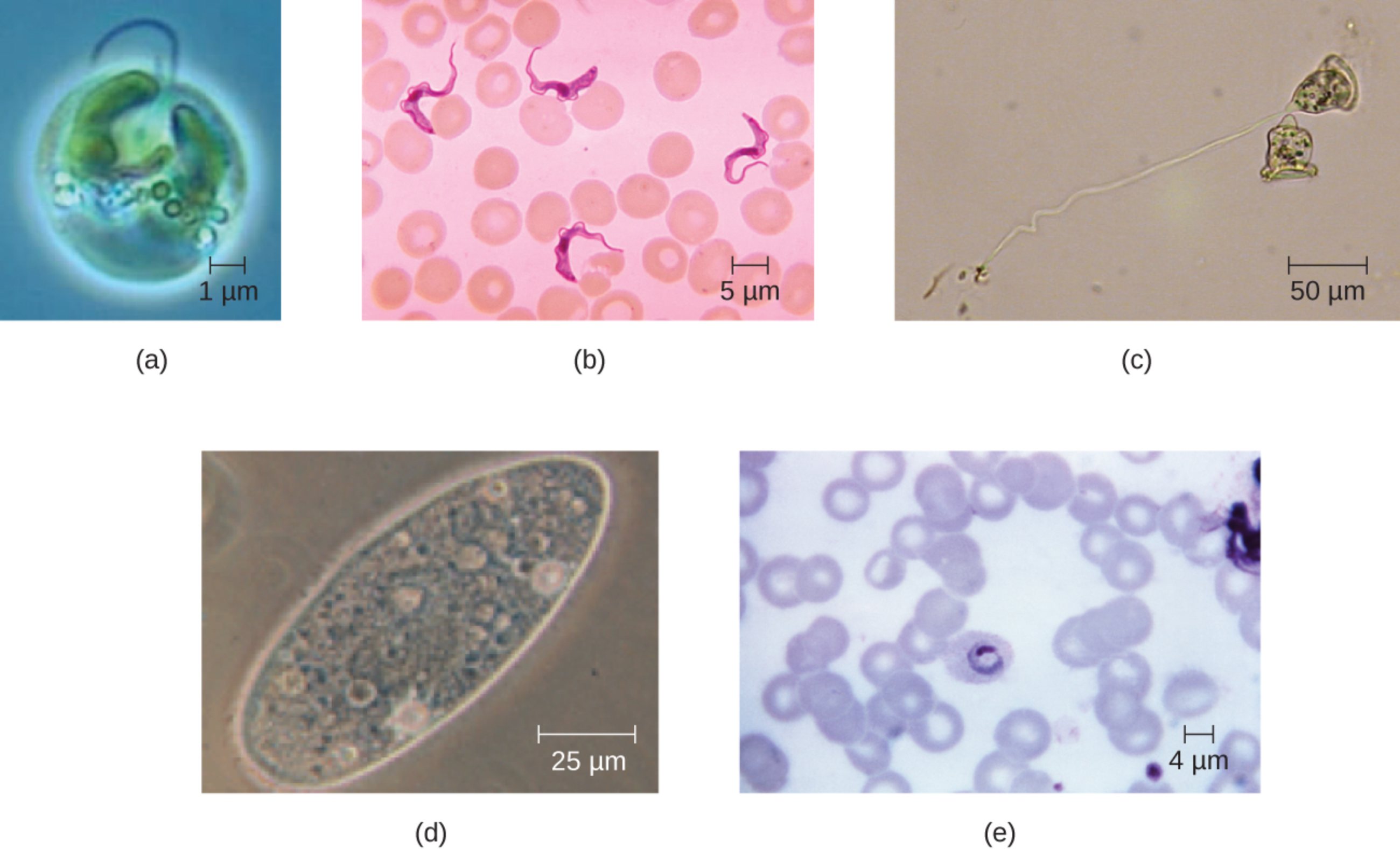

Eukaryotic cells exhibit a remarkable diversity of shapes, a characteristic known as pleomorphism, which is intimately tied to their specific ecological niches and pathogenic mechanisms. From the spheroid algae to the ring-shaped parasites found in human blood, understanding these morphologies is essential for microbiology, pathology, and the diagnosis of infectious diseases.

(a) Spheroid Chromulina alga: This microscopic organism belongs to the golden-brown algae group and is characterized by its nearly perfect spherical shape. This morphology minimizes the surface area to volume ratio, which can be advantageous for maintaining structural integrity and protecting internal organelles in varying aquatic environments.

(b) Fusiform shaped Trypanosoma: These parasites exhibit a spindle-like or fusiform shape, tapering at both ends, which allows them to move efficiently through viscous fluids like human blood. This specific morphology is a hallmark identifying feature used in clinical diagnostics for conditions such as Chagas disease and sleeping sickness.

(c) Bell-shaped Vorticella: Vorticella are predatory ciliates that possess a distinct bell-shaped body usually attached to a contractile stalk. This shape facilitates filter feeding by creating water currents that draw in food particles, demonstrating a clear link between biological form and mechanical function.

(d) Ovoid Paramecium: This well-known protist has an ovoid, elongated shape often described as being resembling a slipper. The streamlined shape, covered in thousands of tiny cilia, allows for rapid swimming and precise maneuvering in complex freshwater habitats.

(e) Ring-shaped Plasmodium ovale: During its early developmental stage inside red blood cells, this parasite appears as a delicate ring-like structure known as a trophozoite. Identifying this specific “ring stage” is a critical step for laboratory technicians performing a peripheral blood smear to diagnose malaria infections.

The vast world of eukaryotic life is not limited to complex multicellular organisms; it includes an incredible array of single-celled entities with diverse morphologies. Eukaryotic cell shape is rarely random. Instead, it is a specialized evolutionary adaptation that supports the cell’s survival, whether through efficient locomotion, nutrient absorption, or evasion of a host’s immune system.

In clinical settings, recognizing these shapes is fundamental to hematology and infectious disease monitoring. For example, the presence of specific parasitic shapes in a patient’s blood sample can immediately signal the presence of a serious infection. These “signatures” of life allow medical professionals to identify pathogens that might otherwise go unnoticed, leading to timely and life-saving medical interventions.

Cellular shapes are influenced by several factors:

- The organization and density of the internal protein framework.

- The presence or absence of a rigid cell wall or pellicle.

- The specific environmental pressures of the organism’s habitat.

- The primary method of movement, such as flagella or cilia.

This structural diversity is particularly evident when comparing free-living organisms to obligate parasites. While a free-living protist relies on its shape for hunting in ponds, a parasite like Plasmodium has adapted a ring-like form to thrive within the confined, nutrient-rich environment of a host’s erythrocyte.

Clinical Significance: Trypanosomiasis and Malaria

The image highlights two of the most significant eukaryotic parasites in human medicine: Trypanosoma and Plasmodium. These organisms are responsible for devastating diseases that affect millions of people globally, and their distinctive shapes are central to how they navigate and colonize the human body.

Trypanosoma species are the causative agents of African Trypanosomiasis. The fusiform shape of these parasites, combined with a powerful flagellum, allows them to navigate the bloodstream and eventually cross the blood-brain barrier. Once they enter the central nervous system, they cause severe neurological symptoms, including disrupted sleep patterns and cognitive decline. Diagnosis often relies on finding these spindle-shaped organisms on a Giemsa-stained blood film.

Plasmodium ovale is one of the species known to cause human malarial disease. The “ring-shaped” appearance shown in the image represents the early trophozoite stage. This parasite invades erythrocytes, where it matures and eventually ruptures the cell, leading to the cyclic fevers and chills characteristic of the infection. Unlike some other species, P. ovale can form dormant stages in the liver, known as hypnozoites, which can cause relapses months later.

The Role of Morphology in Cellular Function

Beyond the realm of pathology, the shapes of free-living eukaryotes like Vorticella and Chromulina illustrate the principles of biophysics. The bell-shape of Vorticella is not just for show; it is an efficient mechanism for creating a vortex in the water. This vortex pulls in bacteria and small particles, which are then processed by the cell’s internal organelles. This demonstrates that even at the microscopic level, “form follows function” is a governing law of nature.

Similarly, the cytoskeleton plays a pivotal role in maintaining these diverse shapes. Microtubules and microfilaments provide a structural scaffold that can be remodeled to allow for movement or changes in volume. In spheroid algae like Chromulina, the cytoskeleton maintains a rigid, protective sphere that can withstand changes in osmotic pressure, ensuring the organism’s survival across different water qualities.

The incredible variety of eukaryotic cell shapes serves as a testament to the adaptability of life on a microscopic scale. Whether an organism is a harmless alga or a dangerous blood parasite, its morphology is a finely tuned tool for survival. By studying these forms, we gain deeper insights into the biological world and the medical challenges we face in treating infectious diseases.