Bacterial locomotion is a sophisticated biological process governed by the rotation of hair-like appendages called flagella. By alternating between coordinated forward movement and sudden changes in direction, microorganisms navigate their environment toward nutrients or away from toxins through a process known as chemotaxis. Understanding these movement patterns provides critical insight into how pathogens colonize host tissues and survive in diverse ecological niches.

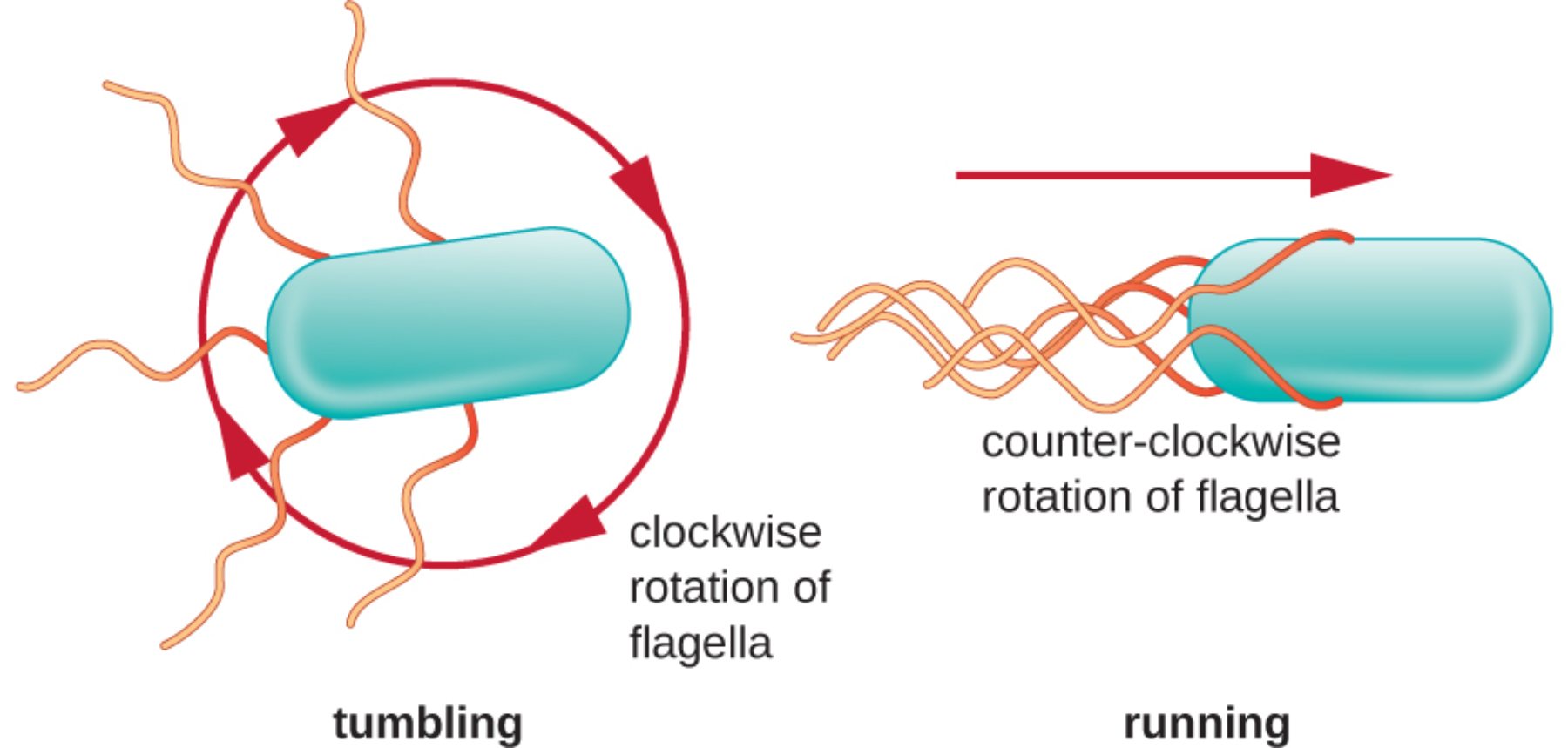

tumbling: This state occurs when the bacterial flagella lose their organized structure and spread out in multiple directions. The resulting motion causes the bacterium to rotate randomly in place, effectively “resetting” its orientation so it can choose a new direction for its next movement.

running: During this phase, the bacterium moves in a smooth, straight line for a sustained period. This is achieved when all flagella bundle together at one end of the cell, acting as a single, powerful propeller that drives the organism forward.

clockwise rotation of flagella: When the flagellar motors rotate in this direction, the physical torque causes the bundle of flagella to fly apart. This mechanical disruption is what triggers the tumbling phase, allowing the cell to cease forward progress and reorient itself in the aqueous medium.

counter-clockwise rotation of flagella: This specific rotational direction is the default state for productive movement in many species. It allows the individual flagellar filaments to wrap around each other to form a cohesive tail, providing the necessary thrust for a linear “run.”

The Physiology of Bacterial Locomotion

Bacteria do not swim aimlessly; rather, their movement is a highly regulated response to external stimuli. The structure of a flagellum is one of nature’s most complex molecular machines, consisting of a basal body that acts as a motor, a hook that functions as a universal joint, and a long filament. In peritrichous bacteria, these flagella are distributed over the entire surface of the cell, requiring precise coordination to facilitate movement.

The decision to run or tumble is managed by a complex internal signaling network. Bacteria use membrane-bound receptors to “taste” their environment, measuring changes in the concentration of attractants or repellents over time. If a bacterium senses it is moving toward a favorable environment, it will suppress tumbling to extend its run.

Several factors influence how and where a bacterium chooses to move:

- Chemical gradients (chemotaxis), such as sugars or amino acids.

- Oxygen levels (aerotaxis), which are vital for aerobic or anaerobic respiration.

- Light intensity (phototaxis), particularly in photosynthetic species.

- Magnetic fields (magnetotaxis), used by some aquatic bacteria to find optimal depths.

The energy required to turn the flagellar motor does not come from ATP hydrolysis directly, but rather from the proton motive force. This is an electrochemical gradient of hydrogen ions across the bacterial cell membrane. As protons flow back into the cell through the motor proteins, the energy is converted into mechanical torque, spinning the flagellum at speeds of up to several hundred revolutions per second.

This alternating pattern of running and tumbling creates what is known as a “biased random walk.” While each tumble chooses a direction at random, the runs are longer when the cell is moving toward a stimulant. Over time, this results in a net migration of the bacterial population toward a more favorable habitat. This signal transduction pathway is essential for the survival of many clinical pathogens, as it allows them to locate and attach to specific host cells during the early stages of an infection.

The ability of bacteria to switch between these two modes of movement is almost instantaneous. A single biochemical switch at the base of the flagellum determines the direction of rotation. When a specific protein, often phosphorylated CheY, binds to the motor, it induces a conformational change that flips the rotation from counter-clockwise to clockwise, immediately transitioning the cell from a run to a tumble. This microscopic engineering ensures that even the simplest organisms can exhibit complex, purposeful behavior in a constantly changing world.

Bacterial motility is a cornerstone of microbial ecology and infectious disease pathology. By mastering the mechanics of the flagellar motor, bacteria can efficiently exploit resources and escape hostile conditions. For medical professionals and researchers, studying these movement patterns is vital for developing new strategies to inhibit bacterial colonization and treat persistent infections effectively.