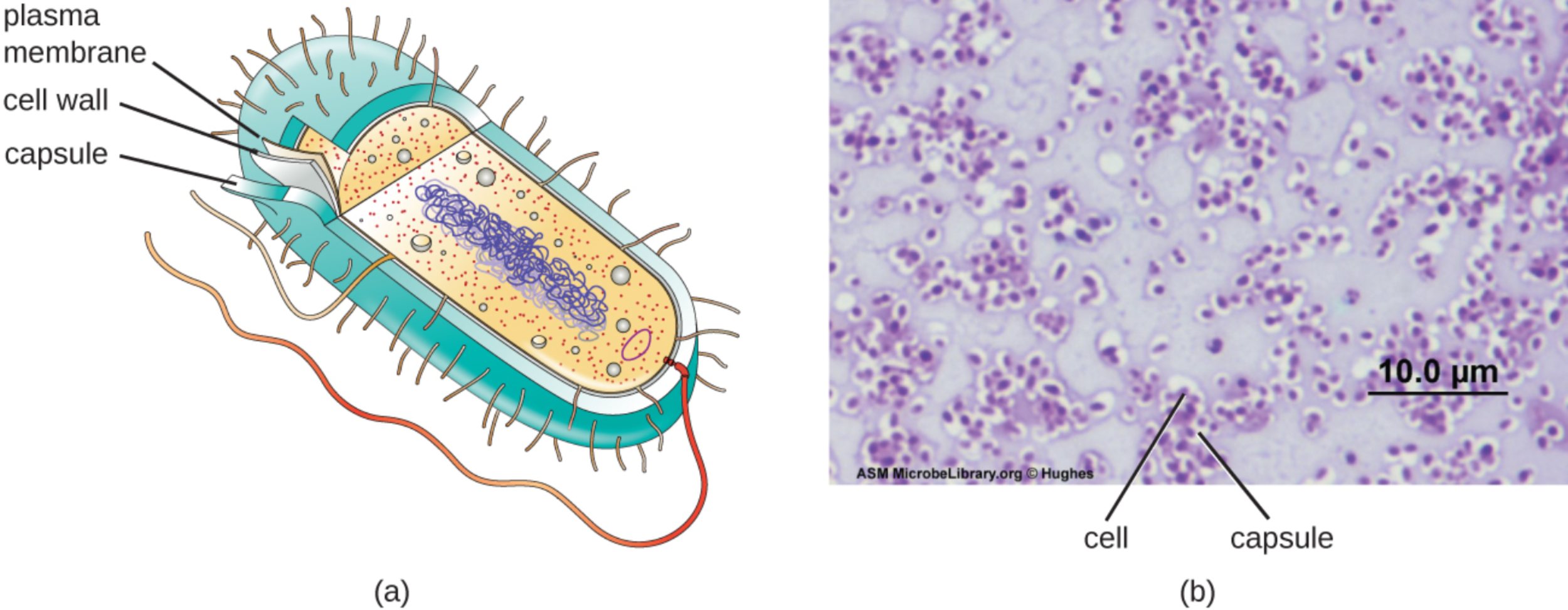

Bacterial capsules are highly organized polysaccharide layers that serve as essential protective barriers for many pathogenic microorganisms. By shielding the cell from environmental stress and host immune responses, capsules enable bacteria like Pseudomonas aeruginosa to establish persistent and often drug-resistant infections. Understanding the anatomical complexity of the bacterial envelope is fundamental to developing effective antimicrobial strategies and improving patient outcomes in clinical settings.

plasma membrane: This is the innermost layer of the bacterial envelope, consisting of a selectively permeable phospholipid bilayer that separates the cytoplasm from the external environment. It is the site for essential metabolic processes, such as ATP production through the electron transport chain and the regulation of molecular transport.

cell wall: Located between the plasma membrane and the capsule, this layer is primarily composed of peptidoglycan to provide necessary structural integrity for the organism. It prevents the bacterium from bursting due to high internal osmotic pressure and maintains the specific shape of the cell, whether it is a coccus or a bacillus.

capsule: This is the outermost coating of the glycocalyx, characterized by a thick and highly organized arrangement of polysaccharides. It serves as a primary defense mechanism, protecting the bacterium from dehydration and, most importantly, preventing phagocytosis by host immune cells like macrophages and neutrophils.

cell: In the context of a specialized capsule stain, this refers to the internal metabolic body of the bacterium where the genetic material and ribosomes are housed. Because capsules do not readily take up most standard dyes, the cell appears as a darkly stained center surrounded by a clear halo-like region.

The Functional Significance of the Bacterial Glycocalyx

The glycocalyx is a sugar-rich coating secreted by many bacteria onto their surface. When this layer is disorganized and loosely attached, it is referred to as a slime layer; however, when it is highly structured and firmly attached to the cell wall, it is classified as a capsule. These structures are more than just physical barriers; they are dynamic interfaces that facilitate bacterial survival in diverse and often hostile environments.

Clinically, the presence of a capsule is one of the most significant virulence factors a bacterium can possess. It essentially masks the surface antigens of the cell, making it “invisible” to the host’s immune system. This allows the pathogen to circulate in the bloodstream or colonize tissues without being immediately targeted for destruction. Furthermore, capsules are integral to the formation of biofilms, which are communities of bacteria embedded in a self-produced matrix.

The primary functions of bacterial capsules include:

- Protection against desiccation (drying out) in the external environment.

- Resistance to host immune defenses, specifically the prevention of opsonization and phagocytosis.

- Assistance in bacterial attachment to surfaces, such as medical implants or host mucosal tissues.

- Acting as a nutrient reserve during periods of starvation.

Because capsules are non-ionic and do not bind to basic dyes, microbiologists use “negative staining” techniques to visualize them. In these procedures, the background and the internal cell are stained, leaving the capsule as a transparent white halo. This diagnostic tool is critical for identifying encapsulated pathogens in clinical samples, such as blood, urine, or sputum.

Pathogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Mucoid Strains

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most formidable opportunistic pathogens encountered in modern healthcare. This Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium is a leading cause of nosocomial infections, particularly among patients who are immunocompromised or those with underlying chronic conditions. Its ability to produce a specialized capsule made of the polysaccharide alginate is a key factor in its clinical success.

In patients with cystic fibrosis (CF), P. aeruginosa often undergoes a phenotypic shift to a “mucoid” state. This transition is characterized by the overproduction of its alginate capsule, which creates a thick, protective extracellular matrix. This mucoid layer protects the bacteria from the high-stress environment of the CF lung, where it faces constant assault from the immune system and high doses of antibiotics. The capsule significantly limits the diffusion of antimicrobial agents, making these chronic lung infections nearly impossible to eradicate.

Beyond respiratory infections, P. aeruginosa is a major threat in burn units. It can colonize damaged skin tissue, utilizing its capsule and pili to adhere and form resilient biofilms that lead to sepsis. It is also frequently associated with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs). The pathogen’s inherent antibiotic resistance, combined with the physical protection of its capsule, creates a therapeutic challenge that requires the use of combination therapies and advanced infection control measures.

Physiological Resilience and Clinical Challenges

The resilience of encapsulated bacteria like Pseudomonas stems from their ability to regulate their envelope in response to the host environment. The capsule acts as a molecular sieve, allowing small nutrients to pass through while blocking larger, harmful molecules like antimicrobial peptides. This physiological advantage ensures that the bacterium remains viable even when the host’s immune system is highly active.

In conclusion, the bacterial capsule is a sophisticated adaptation that bridges the gap between simple cellular structure and complex pathogenesis. Whether protecting a pathogen from the dry surface of a hospital railing or shielding a colony within the lungs of a patient, the capsule remains a primary target for medical research. By continuing to study the biochemical synthesis of these polysaccharide layers, scientists hope to develop new vaccines and treatments that can strip bacteria of their protective armor and restore the efficacy of our current antibiotic arsenal.