Bacterial cell walls are critical structures that define the identity and survival strategies of microorganisms. By distinguishing between Gram-positive and Gram-negative architectures, medical professionals can better understand antibiotic resistance, host-pathogen interactions, and the fundamental physiological differences that drive bacterial behavior. This knowledge is essential for the effective diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases in clinical settings.

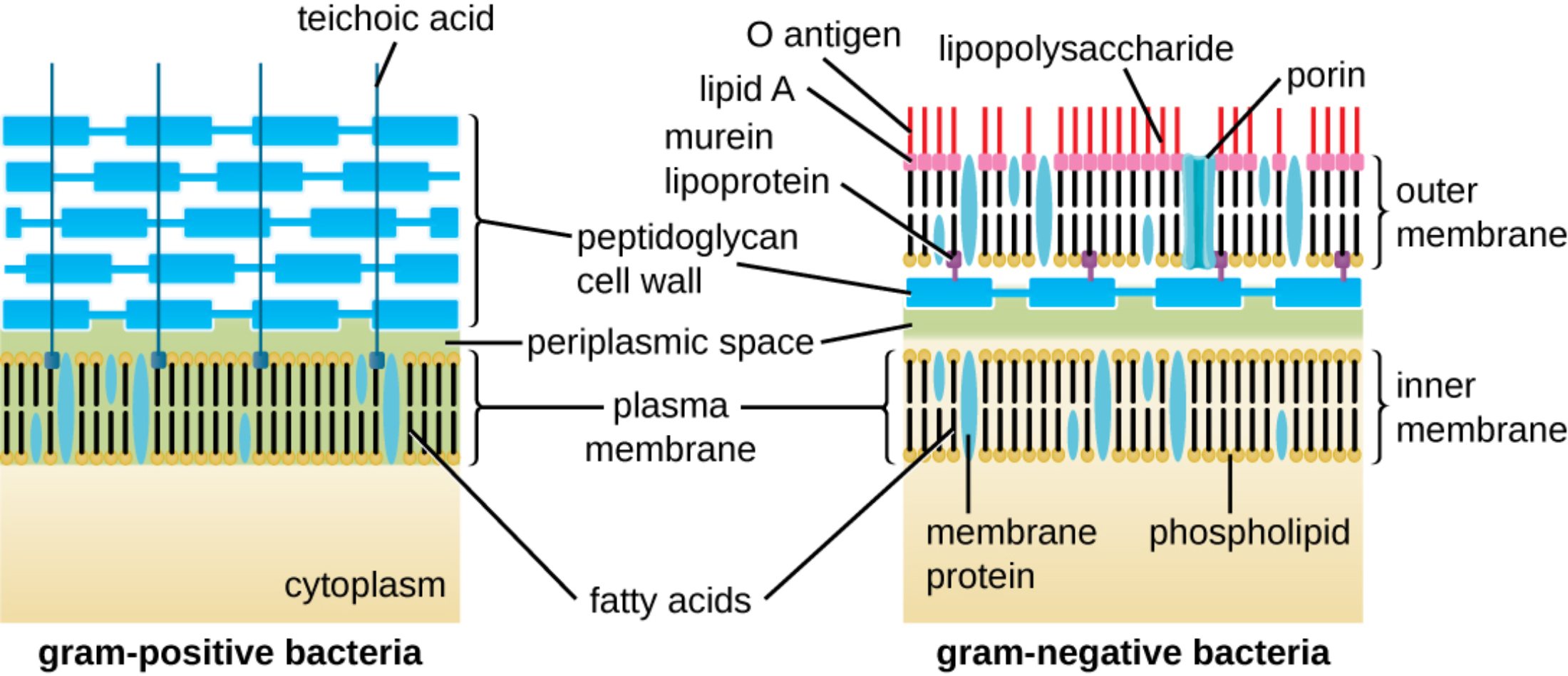

teichoic acid: These are acidic polysaccharides found embedded in the thick peptidoglycan layer of Gram-positive bacteria. They play essential roles in regulating cell division, maintaining cell wall rigidity, and aiding in the attachment to host tissues.

peptidoglycan cell wall: Also known as murein, this is a polymer consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like layer outside the plasma membrane. It provides structural strength to the cell and protects the bacterium from osmotic lysis by maintaining high internal pressure.

periplasmic space: This is the concentrated, gel-like matrix located between the inner cytoplasmic membrane and the bacterial cell wall or outer membrane. It contains a variety of enzymes and proteins responsible for nutrient acquisition, chemical processing, and the degradation of harmful substances.

plasma membrane: This selectively permeable phospholipid bilayer surrounds the cytoplasm and regulates the transport of molecules into and out of the cell. It serves as the primary site for essential metabolic processes, such as ATP production through the electron transport chain.

cytoplasm: The interior gel-like substance where the genetic material and various organelles or inclusions of the bacterium reside. It is the location where most metabolic activities, including protein synthesis and glycolysis, occur in a controlled environment.

fatty acids: These are the hydrophobic components of phospholipids that form the internal core of both the inner and outer membranes. Their chemical composition and saturation levels influence the fluidity and permeability of the bacterial envelope.

O antigen: This is the outermost part of the lipopolysaccharide molecule found in Gram-negative bacteria, extending into the extracellular environment. It is highly variable between species and serves as a primary target for the host’s immune system recognition.

lipid A: This hydrophobic component anchors the lipopolysaccharide into the outer membrane and acts as a potent endotoxin. When released into the host’s bloodstream, it can trigger severe inflammatory responses, leading to conditions such as septic shock.

lipopolysaccharide: Also known as LPS, this complex molecule is a major component of the Gram-negative outer membrane. It consists of lipid A, a core polysaccharide, and an O antigen, providing structural integrity and chemical protection for the cell.

murein lipoprotein: This small protein covalently links the thin peptidoglycan layer to the outer membrane in Gram-negative bacteria. It is one of the most abundant proteins in these organisms, ensuring the stability and cohesion of the entire cell envelope.

porin: These are channel-forming proteins located in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria that allow for the passive diffusion of hydrophilic molecules. They are critical for the uptake of nutrients but can also be modified by the cell to resist certain antibiotics.

outer membrane: This unique lipid bilayer is found only in Gram-negative bacteria and serves as an additional barrier against toxic substances, including many detergents and antibiotics. It contains lipopolysaccharides and porins, which are not present in the Gram-positive cell wall.

inner membrane: Often referred to as the cytoplasmic membrane, this bilayer directly surrounds the cytoplasm and maintains the electrochemical gradient. It is the functional equivalent of the plasma membrane and is found in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative species.

membrane protein: These are diverse proteins embedded within the lipid bilayers that perform functions such as molecular transport, signal transduction, and enzymatic activity. They can be peripheral, loosely attached to the surface, or integral, spanning the entire membrane thickness.

phospholipid: These are the fundamental building blocks of bacterial membranes, consisting of a hydrophilic head and two hydrophobic tails. They spontaneously arrange themselves into bilayers, providing the basic framework for all cellular boundaries.

The Significance of Bacterial Envelopes in Medicine

The classification of bacteria into Gram-positive and Gram-negative categories is one of the most fundamental concepts in microbiology and clinical medicine. This distinction is based on the Gram stain procedure, which identifies the physical and chemical properties of the bacterial cell wall. Gram-positive bacteria are characterized by a thick, multi-layered peptidoglycan meshwork that captures the primary stain, while Gram-negative bacteria possess a much thinner peptidoglycan layer protected by an elaborate outer membrane.

Understanding these structural differences is not merely an academic exercise; it dictates how clinicians approach patient care. The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, for instance, acts as a formidable chemical shield. It prevents many large or hydrophilic molecules from entering the cell, which naturally grants these bacteria resistance to several common antibiotics that would otherwise easily penetrate a Gram-positive wall.

Key structural differences include:

- Peptidoglycan thickness: Thick (20–80 nm) in Gram-positive vs. thin (2–7 nm) in Gram-negative.

- Outer Membrane: Absent in Gram-positive; present in Gram-negative.

- Lipopolysaccharides (LPS): Exclusive to the Gram-negative outer membrane.

- Teichoic Acids: Found only in Gram-positive cell walls.

- Periplasmic Space: Much more prominent and defined in Gram-negative organisms.

The physiological roles of these walls extend to the management of osmotic pressure. Because the interior of a bacterium is often hypertonic compared to its surroundings, the cell wall must provide enough tensile strength to prevent the cell from bursting. This mechanical stability is what allows bacteria to thrive in diverse environments, ranging from human mucosal surfaces to freshwater lakes.

Physiological Defense and Endotoxicity

The Gram-negative outer membrane is particularly noteworthy for its role in pathogenicity. The molecule known as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a hallmark of these bacteria. While LPS provides structural integrity, its lipid A component is medically significant as an endotoxin. When Gram-negative bacteria die or multiply, lipid A is released, which can overstimulate the host’s immune system. This leads to a massive release of cytokines, potentially resulting in fever, vasodilation, and life-threatening hypotension—a clinical state known as sepsis.

Furthermore, the selective permeability of the membranes is managed by specific proteins. In Gram-negative bacteria, porins act as gates, controlling the entry of nutrients while excluding harmful agents. Variations in porin structure or quantity are a common mechanism by which bacteria develop multi-drug resistance. By reducing the number of porins or altering their pore size, a bacterium can effectively “lock the door” against incoming pharmaceutical threats.

Peptidoglycan as a Pharmacological Target

The peptidoglycan layer itself is a prime target for therapy. Human cells do not produce peptidoglycan, making it an ideal site for selective toxicity. For example, beta-lactam antibiotics like penicillin and cephalosporins work by inhibiting the enzymes that cross-link the peptidoglycan strands. Without these links, the wall loses its structural integrity, and the bacterium eventually undergoes lysis due to internal pressure.

However, the efficacy of these drugs depends heavily on their ability to reach the peptidoglycan. In Gram-positive bacteria, the thick layer is directly accessible. In Gram-negative bacteria, the drug must first navigate the outer membrane, which often requires a specific chemical profile or the use of porin channels. This structural nuance is why some antibiotics are labeled as narrow-spectrum (effective against only one group) while others are broad-spectrum.

In conclusion, the bacterial cell wall is a complex and dynamic interface that determines an organism’s survival, its interaction with the host immune system, and its susceptibility to medical treatment. Whether it is the robust, teichoic acid-reinforced wall of a Gram-positive bacterium or the double-membraned, LPS-shielded envelope of a Gram-negative bacterium, these structures are at the heart of microbial physiology. Continued research into these molecular boundaries is essential for the development of the next generation of antimicrobial therapies.