A lumbar puncture, commonly known as a spinal tap, is a critical diagnostic procedure used to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the spinal canal. By accessing the subarachnoid space in the lower back, medical professionals can analyze the fluid for signs of infection, hemorrhage, or neurological disorders. This article explores the anatomical landmarks required for a safe procedure, the optimal patient positioning, and the clinical interpretation of CSF appearance.

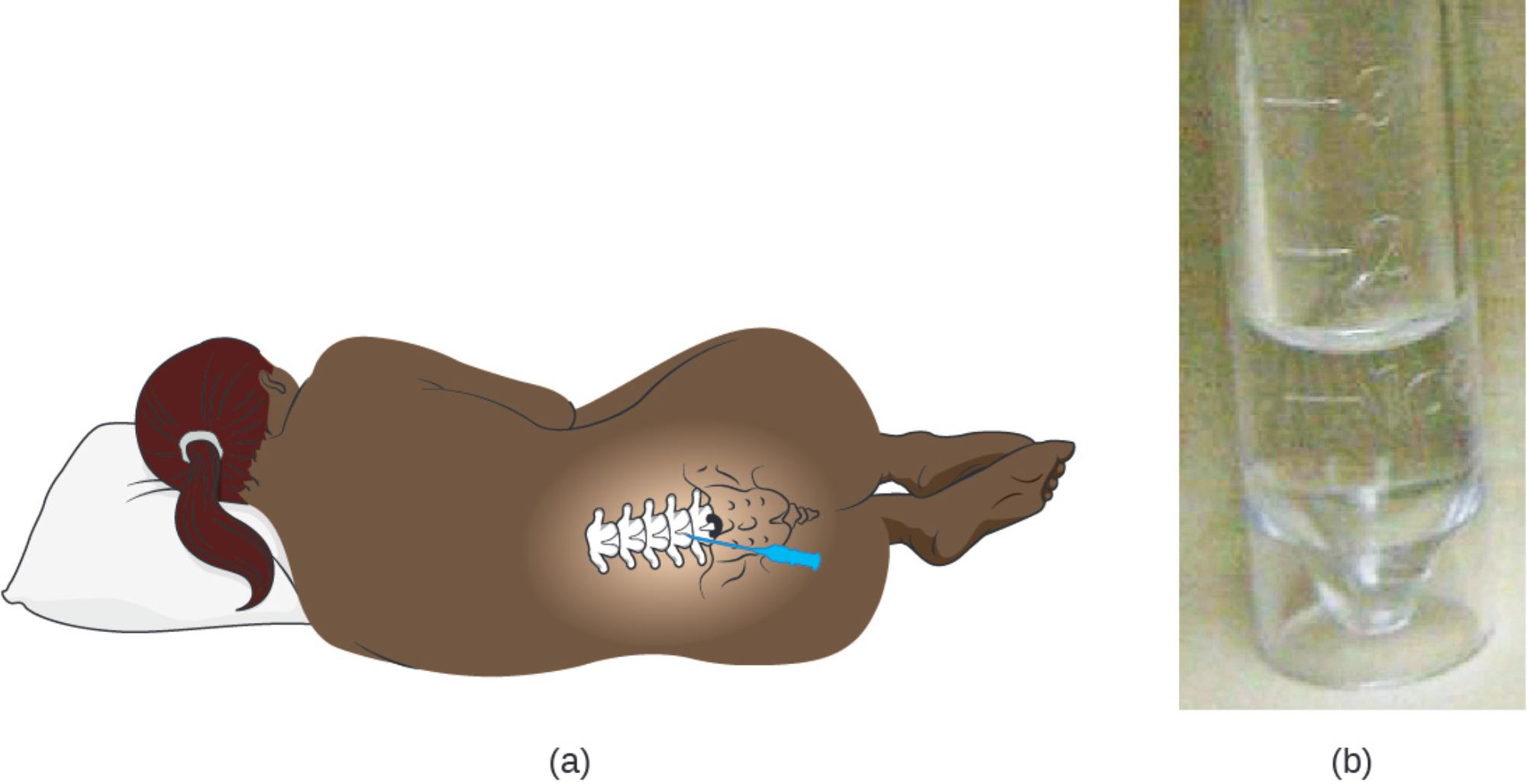

(a): This illustration depicts the lateral recumbent position, which is the standard patient posture for an adult lumbar puncture. The patient lies on their side with the knees drawn up toward the chest and the chin tucked, a position that maximizes the flexion of the spine to widen the intervertebral spaces for easier needle insertion.

(b): This photograph shows a sample of normal cerebrospinal fluid collected in a sterile tube. Healthy CSF should appear visibly indistinguishable from distilled water—colorless and transparent—whereas turbidity or cloudiness suggests the presence of cells, bacteria, or protein associated with pathology.

The Anatomy and Purpose of the Spinal Tap

The lumbar puncture is a definitive diagnostic tool in neurology and emergency medicine. It involves the insertion of a hollow needle into the subarachnoid space of the spinal column to withdraw cerebrospinal fluid for analysis or to measure the opening pressure within the central nervous system. The procedure relies heavily on surface anatomy; clinicians typically identify the L3-L4 or L4-L5 intervertebral spaces by palpating the superior iliac crests of the pelvis, which align with the L4 vertebra. This location is chosen specifically to minimize the risk of neurological injury.

Anatomically, the spinal cord in adults typically terminates at the level of the first or second lumbar vertebra (L1-L2). Below this point, the nerve roots continue as a bundle known as the cauda equina, which floats freely in the CSF. By inserting the needle below the level of the spinal cord termination, the practitioner ensures that the needle enters a space occupied by fluid and mobile nerve roots rather than the solid spinal cord, significantly reducing the risk of direct trauma to the central nervous system tissues.

Once the cerebrospinal fluid is obtained, it serves as a “liquid biopsy” of the brain and spine. The fluid acts as a cushion for the brain, a transport medium for nutrients, and a removal system for metabolic waste. Because the CSF is in direct contact with the brain and spinal cord, changes in its composition—such as cell count, glucose levels, and protein concentration—provide immediate and accurate insights into neurological health.

Common indications for performing a lumbar puncture include:

- Suspected meningitis (bacterial, viral, or fungal).

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage (bleeding around the brain).

- Autoimmune conditions like Multiple Sclerosis or Guillain-Barré syndrome.

- Measurement of intracranial pressure (in cases of idiopathic intracranial hypertension).

- Administration of intrathecal chemotherapy or anesthesia.

Physiological Analysis of Cerebrospinal Fluid

Under normal physiological conditions, CSF is produced by the choroid plexus in the brain’s ventricles. It circulates through the subarachnoid space and is eventually reabsorbed into the venous blood. Normal fluid is acellular or contains very few white blood cells, has a specific glucose level (usually about 60% of blood glucose), and low protein levels. As shown in part (b) of the image, it must be crystal clear.

When a sample appears cloudy or turbid, it is a clinical red flag indicating pleocytosis—an increased number of cells in the fluid. In the context of acute illness, a cloudy sample is highly suggestive of meningitis, an inflammation of the protective membranes (meninges) covering the brain and spinal cord. The cloudiness is caused by the accumulation of white blood cells (neutrophils), bacteria, and elevated proteins that the body sends to the site of infection to fight the invading pathogen. Conversely, fluid that is yellow or “xanthochromic” may indicate the presence of bilirubin, suggesting that a bleed occurred in the brain several hours prior.

Bacterial Meningitis: A Critical Diagnosis

The image description notes that cloudy CSF may indicate an infection, which most commonly points to bacterial meningitis. This is a life-threatening medical emergency requiring immediate antibiotic treatment. Pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae or Neisseria meningitidis can breach the blood-brain barrier, multiplying rapidly within the CSF. Because the immune system responds aggressively, the CSF fills with inflammatory byproducts, altering its appearance from clear to turbid.

Beyond the visual inspection, laboratory analysis is required to confirm the diagnosis. In bacterial meningitis, the lab results typically reveal a high white blood cell count, elevated protein levels (due to the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier), and significantly low glucose levels (hypoglycorrhachia) because the bacteria and white blood cells consume the sugar for energy. Early identification through lumbar puncture allows for targeted therapy, which is essential to prevent permanent neurological damage such as hearing loss, cognitive impairment, or death.

Conclusion

The lumbar puncture remains an indispensable procedure in modern medicine, bridging the gap between physical anatomy and biochemical analysis. By understanding the correct positioning and anatomical landmarks, clinicians can safely access the spinal canal. Furthermore, the visual and chemical examination of the resulting fluid provides crucial data, distinguishing between a healthy central nervous system and potentially fatal conditions like meningitis. The transition from a clear sample to a cloudy one represents a fundamental shift in physiology that directs the course of urgent patient care.