Hemostasis is a complex physiological balancing act involving the formation of blood clots to stop bleeding and the subsequent breakdown of those clots to restore normal blood flow. The process of generating D-dimers begins with the soluble protein fibrinogen and ends with the enzymatic degradation of a stabilized fibrin clot. Understanding this pathway is clinically vital, as the detection of D-dimers in the bloodstream serves as a critical diagnostic marker for thrombotic disorders such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

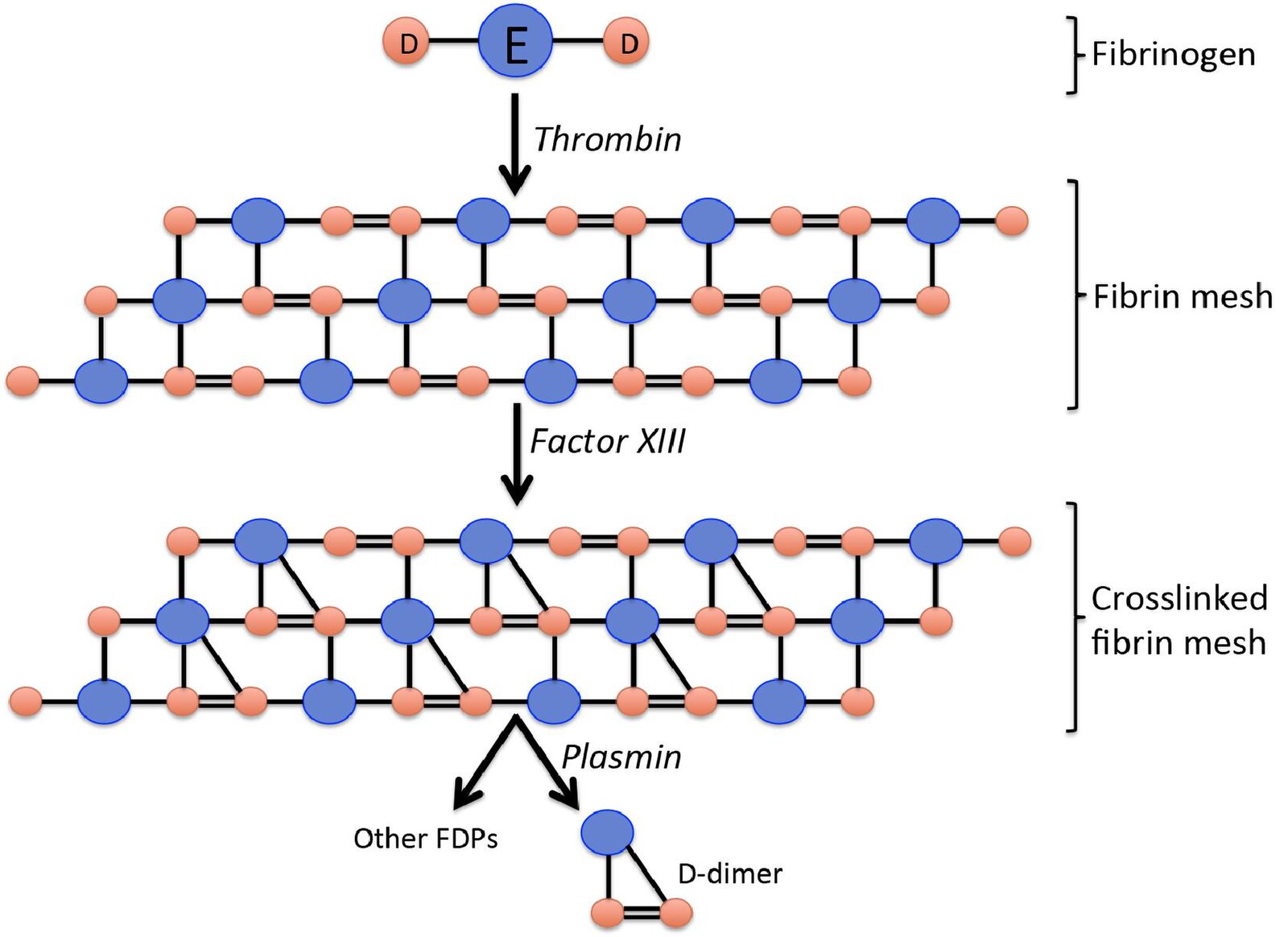

Fibrinogen: This is a large, soluble glycoprotein synthesized by the liver that circulates in the blood plasma. Structurally, as shown in the diagram, it consists of a central E domain connected to two outer D domains, serving as the primary substrate for clot formation.

Thrombin: This is a serine protease enzyme that acts as the primary driver of coagulation. Thrombin cleaves specific peptides from the fibrinogen molecule, activating it and allowing the monomers to polymerize into fibrin strands.

Fibrin mesh: Following the action of thrombin, fibrin monomers spontaneously assemble into a polymer. This network of fibers forms the structural scaffold of a blood clot, trapping blood cells and platelets to seal a vascular injury.

Factor XIII: Also known as fibrin stabilizing factor, this enzyme is activated by thrombin. It introduces covalent bonds between the D domains of adjacent fibrin monomers, significantly strengthening the clot and making it resistant to premature breakdown.

Crosslinked fibrin mesh: This represents the matured, stabilized clot where the fibrin strands are chemically bonded together. The cross-linking between the D domains is essential because it creates the specific D-D bond that eventually results in the formation of D-dimers.

Plasmin: This is the primary enzyme responsible for fibrinolysis, the process of breaking down blood clots. Plasmin acts like biological scissors, cutting through the fibrin mesh at specific sites to dissolve the clot once tissue repair has occurred.

Other FDPs: Standing for Fibrin Degradation Products, these are various fragments of different sizes released during clot breakdown. They include fragments E and separate D monomers that are not linked together.

D-dimer: This is a specific protein fragment produced when plasmin digests cross-linked fibrin. It consists of two D domains held together by the covalent bond formed earlier by Factor XIII, serving as definitive proof that a stable clot was formed and is now being degraded.

The Mechanism of Hemostasis and Fibrinolysis

The process illustrated in the diagram represents the lifecycle of a blood clot, technically known as the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems. When a blood vessel is injured, the body must rapidly convert liquid blood into a semi-solid gel to prevent hemorrhage. However, once the vessel heals, the clot must be removed to prevent the occlusion of blood flow. This removal process is just as regulated as the clot formation itself. The interaction between the coagulation enzymes and the fibrinolytic enzymes ensures that clots are temporary structures used only for physiological repair.

At the molecular level, this process revolves around the structural changes of fibrinogen. Initially soluble, fibrinogen is transformed into insoluble fibrin strands that weave a mesh. The critical step for the eventual production of D-dimers is the stabilization of this mesh. Without the cross-linking action of Factor XIII, the fibrin strands would dissociate easily, and the specific D-dimer fragment would not be created during degradation. Therefore, the presence of D-dimer is specific to the breakdown of cross-linked fibrin, distinguishing it from the breakdown of fibrinogen or unstable fibrin.

In clinical medicine, measuring the byproducts of this pathway is a cornerstone of diagnostic testing. Because D-dimers are only released when a cross-linked clot is degraded, their presence in the blood signals active activation of the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems.

Key components of this physiological pathway include:

- Coagulation Cascade: The series of events leading to thrombin generation.

- Polymerization: The self-assembly of fibrin monomers into a mesh.

- Stabilization: The strengthening of the mesh by Factor XIII.

- Fibrinolysis: The enzymatic dissolution of the clot by plasmin.

Biochemistry of Clot Formation and Stabilization

The transformation of fibrinogen into a stable clot is a precise biochemical event. Fibrinogen is a symmetrical molecule with a central “E” nodule and two terminal “D” nodules. When the coagulation cascade is triggered, the enzyme thrombin cleaves small fibrinopeptides from the central E domain. This exposes binding sites that allow the E domain of one molecule to bind to the D domains of another. This “half-staggered” overlap creates a long, insoluble protofibril, which aggregates laterally to form the fibrin mesh.

However, a mesh formed only by these non-covalent interactions is fragile and susceptible to immediate breakdown. To create a durable seal, the body employs Factor XIII (fibrin stabilizing factor). Activated by thrombin in the presence of calcium, Factor XIII catalyzes a transglutamination reaction. This forms a strong covalent isopeptide bond between the lysine and glutamine residues of adjacent D domains. This “gluing” of the D domains is the defining structural characteristic of a stable thrombus and is the reason D-dimers exist as a distinct entity during degradation.

Clinical Significance: Thrombosis and Diagnostics

The measurement of D-dimer levels is a vital tool in excluding thromboembolic disease. Because D-dimer is a specific degradation product of cross-linked fibrin, its levels are naturally elevated in any condition where the body is forming and breaking down clots. This makes the test highly sensitive for conditions like Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT), Pulmonary Embolism (PE), and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC). In a healthy individual, D-dimer levels are typically very low or undetectable.

If a patient presents with symptoms of a PE (such as shortness of breath or chest pain) or DVT (leg swelling), a normal D-dimer test result effectively rules out the presence of a significant acute clot. This is known as a high negative predictive value. However, because fibrinolysis can occur in various situations—such as after surgery, trauma, infection, or during pregnancy—an elevated D-dimer is not specific to a single disease. Consequently, while a negative D-dimer test can prevent unnecessary imaging, a positive result typically necessitates further diagnostic investigation, such as an ultrasound or CT angiogram, to confirm the location and extent of the thrombosis.

Conclusion

The production of D-dimers is the final biochemical footprint of the body’s effort to heal vascular injury and subsequently restore patency to the vessel. From the initial conversion of fibrinogen by thrombin to the structural reinforcement by Factor XIII and the ultimate cleavage by plasmin, each step is essential for maintaining vascular integrity. Recognizing the specific origin of the D-dimer fragment—specifically its derivation from cross-linked fibrin—allows medical professionals to utilize it effectively as a biomarker for excluding potentially life-threatening thrombotic events.