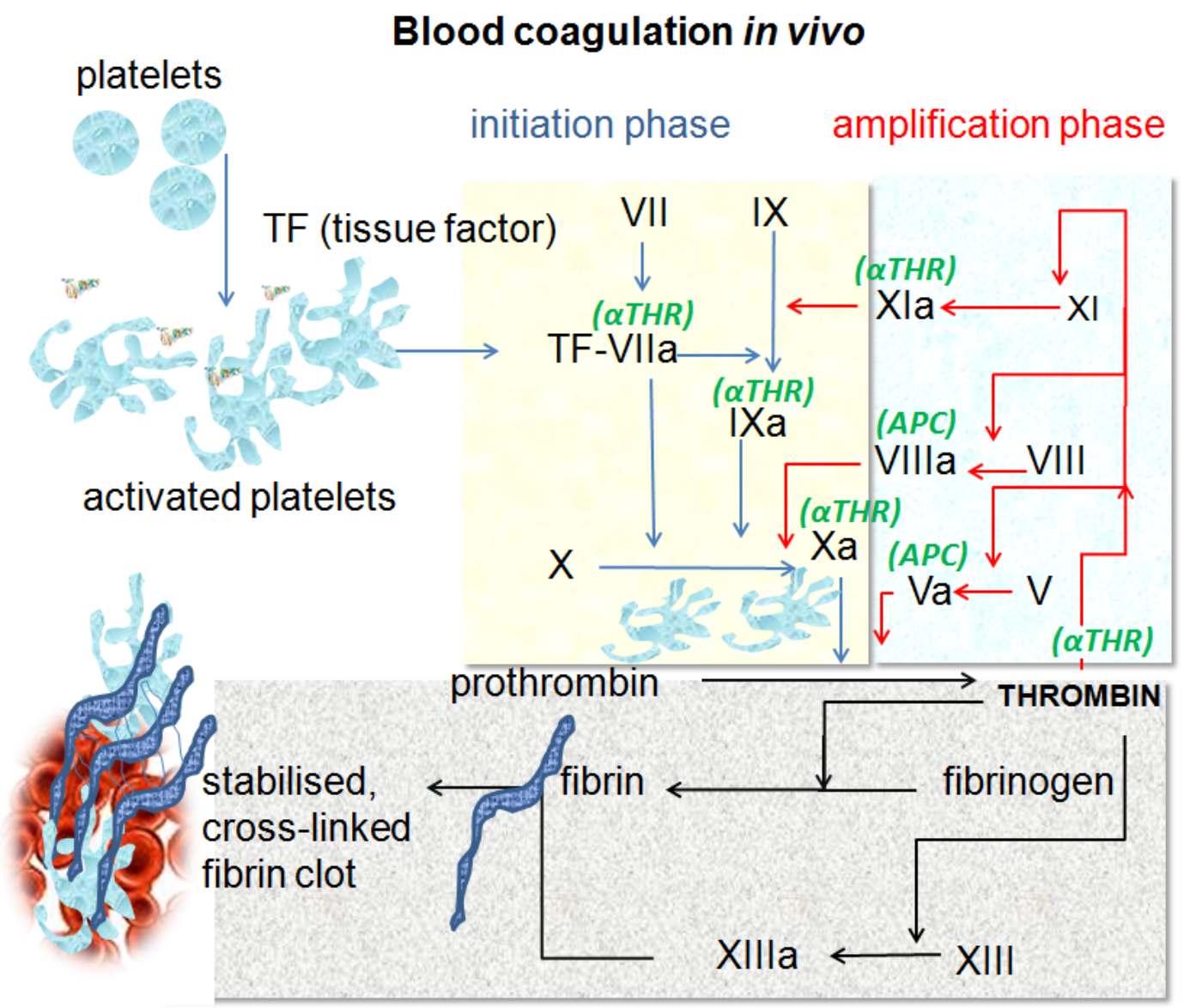

Hemostasis is a sophisticated physiological process designed to maintain the integrity of the circulatory system after vascular injury. This article explores the intricate in vivo mechanism of blood coagulation, detailing how the initiation and amplification phases work synergistically to transform liquid blood into a stable fibrin clot, preventing excessive hemorrhage while maintaining necessary blood flow.

Platelets: These are small, anucleated cell fragments circulating in the blood that are the first responders to vascular injury. Upon detecting damage to the endothelial lining, they adhere to the site and undergo activation to form a temporary plug.

Activated platelets: Once triggered by injury signals, platelets change shape to become spiky and “sticky,” increasing their surface area. This morphological change allows them to bind clotting factors and serve as a catalytic surface for the coagulation reactions.

TF (tissue factor): Also known as Factor III, this is a transmembrane protein found on sub-endothelial cells (like fibroblasts) that are not normally exposed to blood. It acts as the primary physiological initiator of coagulation when a blood vessel is damaged.

Initiation phase: This phase represents the beginning of the coagulation process, indicated by the blue arrows in the diagram. It occurs on cells expressing Tissue Factor and generates a small, initial amount of thrombin to kickstart the system.

Amplification phase: Highlighted by the red arrows, this phase occurs on the surface of activated platelets. Here, the small amount of thrombin generated during initiation activates other cofactors to produce a massive “burst” of thrombin production.

TF-VIIa: This is the complex formed when Tissue Factor binds with circulating Factor VIIa. This enzymatic complex is crucial as it activates Factor IX and Factor X, effectively starting the enzymatic cascade.

VII (Factor VII): A serine protease circulating in the blood. It binds to Tissue Factor at the site of injury and is rapidly converted to its active form (VIIa).

IX / IXa (Factor IX): This enzyme is activated by the TF-VIIa complex during initiation or by Factor XIa during amplification. Factor IXa acts as a key component of the “tenase” complex, which activates Factor X.

X / Xa (Factor X): This factor sits at the convergence of the coagulation pathways. Once activated into Factor Xa, it pairs with Factor Va to convert prothrombin into thrombin, a pivotal step in the process.

XI / XIa (Factor XI): During the amplification phase, thrombin activates Factor XI. Factor XIa then boosts the production of Factor IXa, ensuring the process continues robustly even after the initial Tissue Factor signal is covered by the forming clot.

VIII / VIIIa (Factor VIII): Often associated with Hemophilia A, this protein acts as a cofactor. Thrombin activates it to Factor VIIIa, which then massively speeds up the activity of Factor IXa.

V / Va (Factor V): This is another essential cofactor activated by thrombin. Factor Va binds to Factor Xa on the platelet surface to form the prothrombinase complex, which accelerates thrombin generation significantly.

Prothrombin: This is the inactive precursor (zymogen) to thrombin. It circulates freely in the plasma until it is cleaved by Factor Xa.

Thrombin: The central enzyme of the coagulation cascade (Factor IIa). It not only converts fibrinogen to fibrin but also acts as a powerful activator of platelets and Factors V, VIII, XI, and XIII, creating a positive feedback loop.

Fibrinogen: A soluble plasma protein produced by the liver. Under the influence of thrombin, it is converted into insoluble fibrin strands.

Fibrin: These are the thread-like protein strands that form a meshwork. This mesh traps blood cells and platelets to form the structural basis of the clot.

XIII / XIIIa (Factor XIII): Activated by thrombin, this enzyme acts as a transglutaminase. It cross-links the fibrin strands, making the mesh significantly stronger and resistant to premature breakdown.

Stabilised, cross-linked fibrin clot: This is the final product of hemostasis. It is a durable seal composed of a cross-linked fibrin mesh holding platelets and red blood cells, effectively stopping bleeding and allowing tissue repair to begin.

aTHR (Antithrombin): Indicated in green, this is a naturally occurring inhibitor. It regulates the process by neutralizing enzymes like Thrombin, Factor Xa, and Factor IXa to prevent the clot from growing too large.

APC (Activated Protein C): Another regulatory protein shown in green. It degrades the activated cofactors Va and VIIIa, acting as a “brake” on the coagulation cascade to prevent thrombosis.

The Cell-Based Model of Hemostasis

The mechanism of blood coagulation was historically taught as a “waterfall” or “cascade” of proteins, but modern medicine utilizes the cell-based model of hemostasis, as depicted in the provided image. This model emphasizes that coagulation is not just a fluid-phase reaction but occurs on specific cell surfaces. It separates the physiological process into three distinct but overlapping phases: initiation, amplification, and propagation. This distinction is vital for understanding how the body localizes clot formation to the site of injury, preventing dangerous clotting in healthy vessels.

The process begins when blood vessels are damaged, exposing the blood to extravascular cells bearing Tissue Factor. This “Initiation” step produces a trace amount of thrombin—just enough to wake up the system. The subsequent “Amplification” phase relocates the process to the surface of activated platelets. Here, the initial thrombin activates critical cofactors (Factors V and VIII), priming the platelets to support massive thrombin generation. This biological design ensures that a robust clot is formed quickly, but only where it is needed.

To maintain a healthy vascular system, the body relies on a delicate balance of several components:

-

Procoagulants: Enzymes and factors that promote clotting (e.g., Thrombin, Factor X).

-

Anticoagulants: Natural inhibitors that limit clotting (e.g., Antithrombin, Protein C).

-

Fibrinolytic system: Mechanisms that eventually break down the clot once healing has occurred.

-

Cellular elements: Specifically platelets and endothelial cells that host these reactions.

Detailed Physiology of the Coagulation Pathways

The physiological journey from liquid blood to a solid gel involves a series of enzymatic activations. In the initiation phase, the Tissue Factor-Factor VIIa complex activates Factor X and Factor IX. While Factor Xa can generate a small amount of thrombin directly, this is rapidly inhibited by Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor (TFPI) and Antithrombin (aTHR). Therefore, the system requires the amplification loop. The trace thrombin generated recruits platelets and activates Factors V, VIII, and XI.

This amplification leads to the “propagation” phase (often implied in the formation of the stabilized clot). On the surface of the activated platelet, the “Tenase Complex” (Factor IXa + Factor VIIIa) activates Factor X extremely efficiently. This Factor Xa then combines with Factor Va to form the “Prothrombinase Complex.” This complex converts prothrombin to thrombin at an explosive rate. This “thrombin burst” is what allows for the rapid conversion of soluble fibrinogen into the insoluble fibrin meshwork.

Finally, the clot must be stabilized. The fibrin strands initially formed are relatively weak and can be easily broken. Thrombin activates Factor XIII (Fibrin Stabilizing Factor), which creates covalent cross-links between the fibrin strands. This transforms the mesh into a rigid, durable structure capable of withstanding arterial blood pressure. Simultaneously, regulatory mechanisms like Activated Protein C (APC) work to degrade Factors Va and VIIIa, ensuring the clot does not expand beyond the site of injury, which could otherwise lead to thrombosis (pathological clotting).

Conclusion

The in vivo blood coagulation pathway is a marvel of biological engineering, balancing the need for rapid response with strict regulatory control. By utilizing a cell-based approach involving initiation, amplification, and stabilization, the body ensures that bleeding is halted efficiently without compromising general circulation. Understanding these specific pathways, including the roles of thrombin, fibrin, and natural inhibitors like antithrombin, is essential for diagnosing and treating coagulation disorders such as hemophilia or deep vein thrombosis.