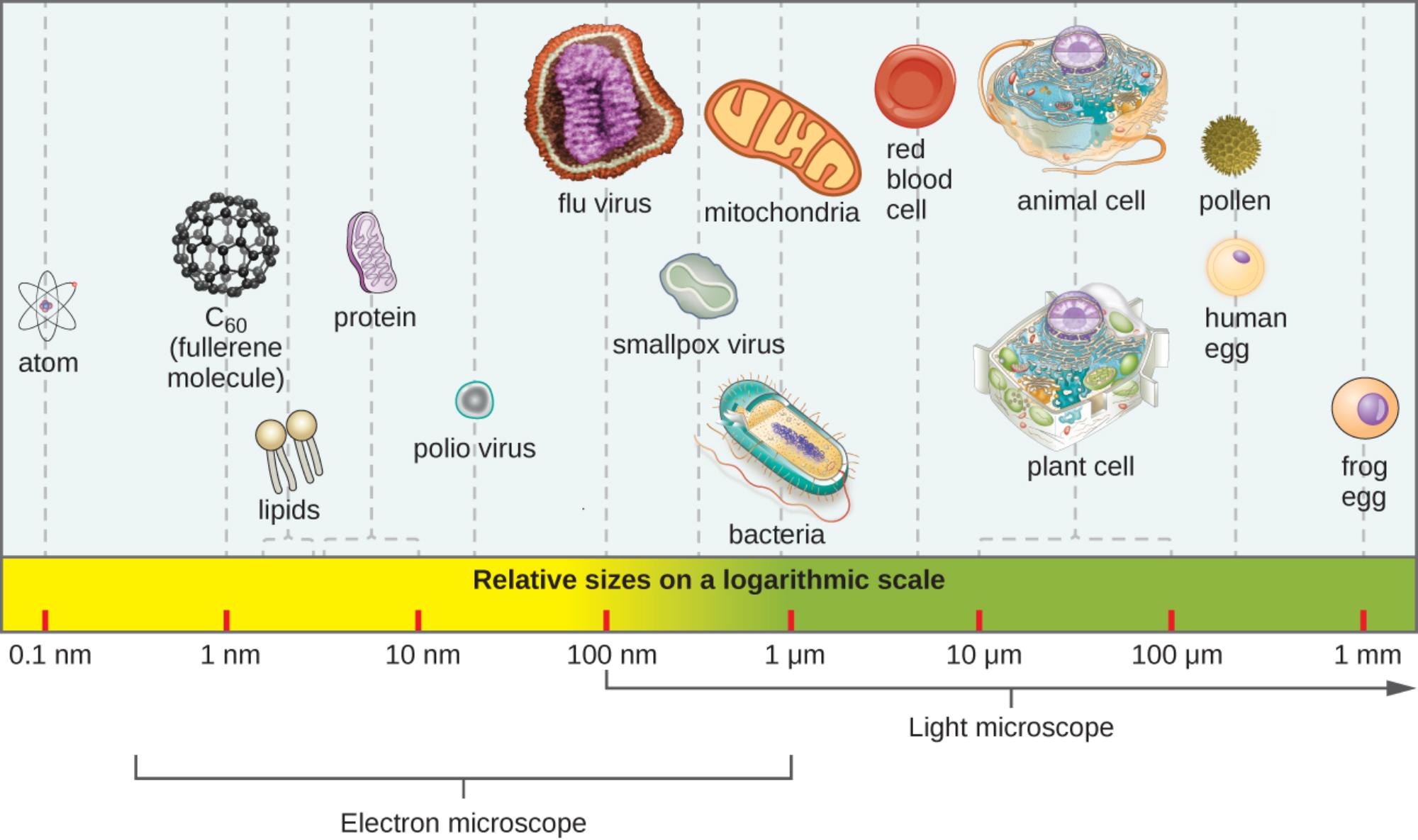

This comprehensive guide explores the vast differences in scale within the biological world, comparing the relative sizes of microscopic and nonmicroscopic objects on a logarithmic scale. From the fundamental atom to complex multicellular structures, we examine how different imaging technologies, such as light and electron microscopes, are required to visualize the building blocks of life and the pathogens that affect them.

Atom: As the fundamental unit of matter, the atom sits at the far left of the scale, measuring approximately 0.1 nanometers (nm). It consists of a dense nucleus surrounded by a cloud of electrons and serves as the basic building block for all chemical and biological structures.

C60 (fullerene molecule): Also known as a “buckyball,” this is a spherical molecule composed of 60 carbon atoms arranged in a cage-like structure. Measuring roughly 1 nanometer in diameter, it represents complex molecular geometry and is significantly larger than a single atom but smaller than biological macromolecules.

Lipids: These amphipathic molecules are the fundamental structural components of cell membranes, measuring roughly 2 to 3 nanometers. They typically consist of a hydrophilic head and a hydrophobic tail, allowing them to form the bilayers that encase cells and organelles.

Protein: Proteins are large, complex molecules composed of chains of amino acids, generally ranging from 5 to 10 nanometers in size. They perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalyzing metabolic reactions as enzymes, DNA replication, and transporting molecules.

Polio virus: This is a small, non-enveloped RNA virus responsible for poliomyelitis, measuring approximately 30 nanometers in diameter. Its minute size makes it significantly smaller than many other viral pathogens and requires high-resolution electron microscopy to be visualized.

Flu virus: The influenza virus is an enveloped virus that typically ranges from 80 to 120 nanometers, roughly 100 nm on average. It is spherical or filamentous in shape and contains RNA genetic material responsible for seasonal respiratory infections.

Smallpox virus: One of the largest and most complex viruses, the Variola virus measures approximately 200 to 300 nanometers. Its relatively large size borders on the resolution limit of high-powered light microscopes, though it is best viewed via electron microscopy.

Mitochondria: Often referred to as the powerhouse of the cell, these organelles measure about 1 micrometer (µm) in length. They are responsible for generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through cellular respiration and are believed to have originated from ancient symbiotic bacteria.

Bacteria: These prokaryotic organisms typically range from 1 to 5 micrometers in size, making them significantly larger than viruses but smaller than eukaryotic cells. They lack a membrane-bound nucleus and can exist in various shapes, such as rods, spheres, or spirals.

Red blood cell: Also known as an erythrocyte, this biconcave cell measures approximately 7 to 8 micrometers in diameter. It is specialized for oxygen transport in the circulatory system and lacks a nucleus when mature to maximize space for hemoglobin.

Animal cell: These eukaryotic cells generally range from 10 to 30 micrometers and lack a rigid cell wall, which allows for diverse shapes and tissue formation. They contain membrane-bound organelles, including a nucleus, and serve as the structural units for tissues in animals.

Plant cell: Typically larger than animal cells, plant cells range from 10 to 100 micrometers and are encased in a rigid cellulose cell wall. They often contain chloroplasts for photosynthesis and a large central vacuole that maintains turgor pressure.

Pollen: These coarse, powdery grains contain the male microgametophytes of seed plants and generally measure between 20 and 50 micrometers. Their size varies greatly by species and they are easily visible under a standard light microscope; they are also common allergens.

Human egg: The ovum is one of the largest cells in the human body, measuring approximately 100 to 120 micrometers (0.1 mm). It is just barely visible to the naked eye under optimal conditions, appearing as a tiny speck without magnification.

Frog egg: These large reproductive cells measure approximately 1 millimeter (mm) in diameter, making them easily visible without any magnification. They serve as a classic model for embryological studies due to their large size and external development.

Understanding Biological Magnitude

The biological world operates across a staggering range of sizes, necessitating the use of a logarithmic scale to visualize relationships meaningfully. In a linear scale, the difference between an atom and a frog egg would be impossible to graph effectively; however, the logarithmic approach allows us to see that biological complexity increases in multiples of ten. At the molecular level, we deal with nanometers (nm), which are one-billionth of a meter. As we move up the ladder of life, we cross into micrometers (µm), or one-millionth of a meter, and finally into millimeters (mm), which are visible to the human eye.

This hierarchy of size is not just a matter of measurement but of functional complexity. At the lowest end, atoms combine to form molecules like lipids and proteins. These macromolecules assemble to form organelles like mitochondria and structures like viral capsids. A key observation from the provided image is the “Rule of 10” often cited in introductory biology: a typical virus (100 nm) is roughly 10 times smaller than a bacterium (1 µm), which is in turn about 10 times smaller than a typical eukaryotic cell (10–100 µm). This progression highlights the compartmentalization necessary for life; a cell must be large enough to house the machinery (organelles, DNA, ribosomes) required to sustain itself.

To study these diverse structures, scientists must utilize different tools based on resolution limits. The human eye has a resolution limit of about 100 micrometers (0.1 mm), meaning we can see a frog egg or a large human egg, but nothing smaller. To bridge the gap, optical technology is employed:

- Electron Microscopes: Required for objects between 0.1 nm and 100 µm, such as atoms, viruses, and cellular organelles.

- Light Microscopes: Suitable for objects between 200 nm and several millimeters, effectively visualizing bacteria, plant cells, and pollen.

- The Naked Eye: Effective only for macroscopic objects larger than 100 µm.

The Medical Significance of Scale

In medical science, understanding these relative sizes is crucial for diagnosis, pathology, and pharmacology. The distinction between the size of a virus and a bacterium, for example, dictates how we detect and treat infections. Because viruses like Polio or Influenza are in the nanometer range, they pass through standard bacterial filters and cannot be seen during a standard urinalysis or tissue culture under a light microscope. This necessitates advanced diagnostic techniques like Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) or electron microscopy to identify viral pathogens.

Conversely, bacteria and eukaryotic parasites are large enough to be identified with standard staining techniques and light microscopy. This size difference also influences treatment mechanisms. For instance, the cell wall of a bacterium is a massive structure compared to a drug molecule; antibiotics are designed as tiny chemical keys (molecular scale) that fit into specific locks within the bacterial machinery. Furthermore, the large size of human cells compared to viruses explains how a single cell can become a factory for thousands of viral particles, which hijack the cell’s resources to replicate within the tiny intracellular spaces.

Conclusion

Visualizing the relative sizes of microscopic and nonmicroscopic objects provides a fundamental framework for understanding biology. From the atomic composition of fullerene molecules to the complex architecture of a frog egg, nature is organized across a vast spectrum of magnitude. Recognizing that a bacterium is significantly larger than a virus, yet dwarfed by a plant cell, helps contextualize the interactions that drive health, disease, and the very structure of life. This knowledge of scale is the foundation upon which modern microbiology, histology, and pharmacology are built.