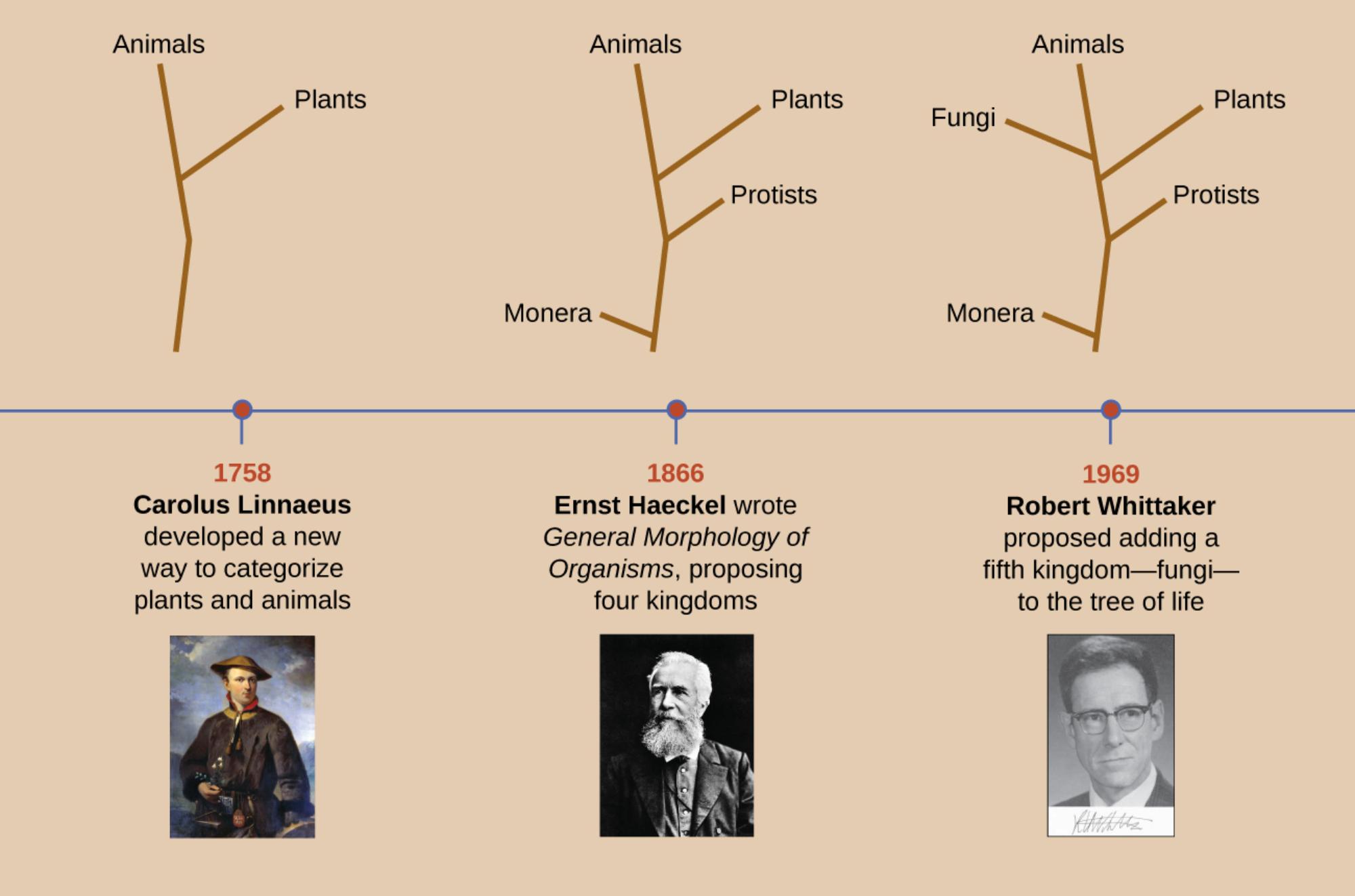

The scientific categorization of living things has undergone profound transformations over the centuries, evolving from simple visual observations to complex genetic analyses. This timeline illustrates the major shifts in the “Tree of Life,” highlighting how our understanding of biological relationships expanded from Carolus Linnaeus’s fundamental two-kingdom system to Robert Whittaker’s comprehensive five-kingdom model. These changes reflect significant advancements in technology and our deepening knowledge of the anatomical and physiological distinctions between organisms.

1758 Carolus Linnaeus: This section marks the foundation of modern taxonomy, where the Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus established a binary system of classification. He categorized all living organisms into two distinct kingdoms—Animals and Plants—based primarily on observable physical traits such as motility and the method of obtaining nutrients.

1866 Ernst Haeckel: A century later, German biologist Ernst Haeckel expanded the tree to address microscopic life forms that did not fit neatly into the plant or animal categories. In his book General Morphology of Organisms, he proposed a system that included four kingdoms by adding Protista (for single-celled eukaryotes) and Monera (for simple, single-celled organisms like bacteria), acknowledging the vast diversity revealed by the microscope.

1969 Robert Whittaker: This point on the timeline represents the establishment of the five-kingdom system, which became the standard for late 20th-century biology. Whittaker recognized that fungi were fundamentally different from plants in their cellular structure and physiology, prompting him to create a distinct kingdom for Fungi alongside Animals, Plants, Protists, and Monera.

The Dynamic Nature of Taxonomy

The classification of life is not a static catalog but a dynamic field that shifts alongside our ability to observe the natural world. In the 18th century, before high-powered microscopes and genomic sequencing were available, scientists relied on macroscopic morphology. If an organism moved and ate, it was an animal; if it was rooted and green, it was a plant. As shown in the timeline, this binary view eventually proved insufficient as researchers discovered the teeming world of microorganisms that possessed characteristics of both, or neither, of the original groups.

The transition from a two-kingdom to a five-kingdom system represents a move toward understanding organisms at a cellular and biochemical level. For instance, the separation of fungi from plants was not merely a cosmetic change but a recognition of profound physiological differences, such as the composition of cell walls and metabolic pathways. This refinement is crucial for medical science, as understanding the biological distinctiveness of a pathogen—whether it is bacterial, fungal, or parasitic—dictates the pharmacological approach to treatment.

Today, taxonomy continues to evolve, often driven by molecular data that reveals evolutionary relationships invisible to the naked eye. While the timeline culminates in 1969, it sets the stage for modern phylogenetics, which groups organisms based on shared ancestry and genetic markers. This evolution in thought helps researchers and clinicians predict how different organisms will interact with the human body and the environment.

Key drivers of taxonomic evolution include:

- The invention and refinement of the optical microscope.

- The discovery of the electron microscope, allowing views of internal cell structures.

- Advances in biochemistry and the understanding of metabolic modes (photosynthesis vs. absorption).

- The development of genetic sequencing and molecular biology.

From Morphology to Cellular Physiology

The expansion of the taxonomy system illustrated in the timeline is largely a story of understanding cellular physiology. In the Linnaean system (1758), the distinction was functional: motility versus stability. However, this failed to account for fungi, which are immobile like plants but do not perform photosynthesis. It also failed to categorize bacteria, which are microscopic and structurally distinct from both plants and animals.

Haeckel’s contribution (1866) was the recognition of the microscopic world. By introducing Monera, he created a category for organisms that we now identify as prokaryotic. These are single-celled organisms lacking a membrane-bound nucleus, a defining feature that separates bacteria from the complex eukaryotic cells found in animals and plants. This distinction is the basis of modern antibiotic therapy; many antibiotics work by targeting the specific structural components of prokaryotic cells, such as the peptidoglycan cell wall, while leaving human eukaryotic cells unharmed.

The Distinction of Fungi and Modern Implications

Whittaker’s 1969 proposal to elevate Fungi to their own kingdom was a critical physiological correction. Previously grouped with plants, fungi are actually heterotrophic, meaning they acquire nutrients by absorbing organic material from their environment, much like animals, rather than producing it through photosynthesis. Furthermore, while plant cell walls are made of cellulose, fungal cell walls are composed of chitin. This biochemical detail is vital in medicine; antifungal medications must target the synthesis of ergosterol or chitin to be effective, mechanisms that are entirely different from herbicides or antibiotics.

The progression shown in this image underscores the importance of precision in medical biology. A misclassification is not just an academic error; it can lead to a misunderstanding of how an organism survives, reproduces, and causes disease. By refining the Tree of Life, scientists have provided a roadmap that allows for the development of targeted treatments and a deeper understanding of the ecological roles played by microbes, fungi, and multicellular organisms alike.

Conclusion

The timeline of the Tree of Life serves as a historical record of scientific clarity. From Linnaeus’s initial broad strokes to Whittaker’s specific five-kingdom structure, each step forward was propelled by a deeper understanding of anatomical and physiological reality. This continuous refinement of biological classification remains essential today, as it provides the framework through which medical professionals identify pathogens, understand human physiology in the context of evolution, and develop specific therapies for a wide range of biological threats.