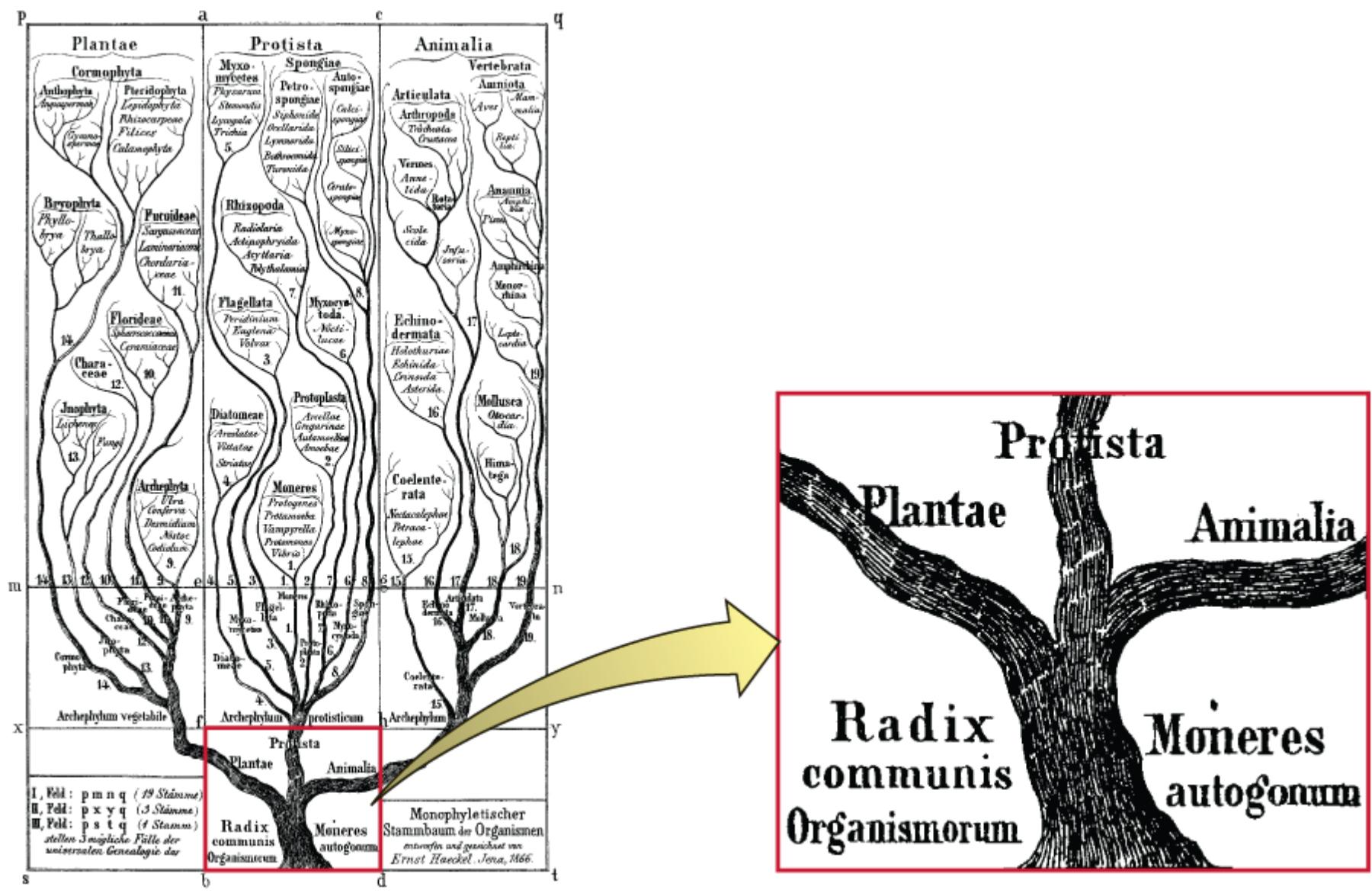

This article explores the historical significance of Ernst Haeckel’s 1866 phylogenetic tree, a pioneering visual representation that revolutionized how scientists understand the evolutionary relationships between living organisms. We will delve into the categorization of life into kingdoms such as Plantae, Protista, and Animalia, and examine how these early concepts laid the groundwork for modern evolutionary biology, taxonomy, and the medical understanding of microbial life.

Plantae: This kingdom encompasses all multicellular plants, ranging from primitive mosses to complex flowering plants (angiosperms). In Haeckel’s classification, this branch represents autotrophic organisms that primarily generate energy through photosynthesis and possess rigid cell walls made of cellulose.

Protista: Haeckel introduced this kingdom to categorize organisms that did not fit neatly into the traditional plant or animal categories, including single-celled eukaryotes like algae and protozoa. It served as a necessary classification for primitive forms of life that exhibited characteristics of both plants and animals, or neither, acting as a bridge in the evolutionary timeline.

Animalia: This major branch represents the animal kingdom, consisting of multicellular, heterotrophic organisms that consume organic material for sustenance. This group includes a vast diversity of life, from simple invertebrates like sponges and worms to complex vertebrates, including mammals and humans.

Radix communis Organismorum: Translated from Latin as the “common root of organisms,” this label illustrates the concept of a single common ancestor for all life forms. It visualizes the theory of monophyly, suggesting that all three main branches—plants, protists, and animals—diverged from the same primordial origin point.

Moneres autogonum: This term refers to the simplest, microscopic organisms that Haeckel believed were the earliest forms of life, which he hypothesized arose through spontaneous generation. These organisms, later classified under the kingdom Monera, represent prokaryotic life forms that lack a distinct nucleus, such as bacteria.

The Dawn of Phylogenetic Classification

Ernst Haeckel, a prominent German biologist and philosopher, created this “Tree of Life” in his 1866 book General Morphology of Organisms. Before this visualization, biological classification was largely based on the Linnaean system, which grouped organisms based on shared physical characteristics but did not necessarily account for their evolutionary history. Haeckel was a strong proponent of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, and this diagram was one of the first attempts to visually map the genealogy of all living things, suggesting that all species share a common descent.

The primary innovation in this diagram was the introduction of the kingdom Protista. Prior to Haeckel, scientists generally categorized all life as either plant or animal. However, the discovery of microscopic organisms that moved like animals but photosynthesized like plants created a taxonomic crisis. By establishing Protista, and later Monera (for bacteria and blue-green algae), Haeckel provided a framework that acknowledged the complexity of the microbial world. This was a crucial step in the development of microbiology, a field essential to modern medicine.

Haeckel’s work shifted the scientific perspective from a static view of nature to a dynamic, evolutionary one. While modern genetics has refined and corrected many of his specific placements, the overarching concept of a “tree of life” remains the dominant metaphor in evolutionary biology. It helps researchers trace the lineage of pathogens and understand the genetic similarities between humans and other organisms.

Key contributions of Haeckel’s phylogenetic tree include:

- The visualization of evolution as a branching process rather than a linear ladder.

- The introduction of the kingdom Protista to classify single-celled organisms.

- The proposal of a common ancestor (Radix communis) for all life forms.

- The early distinction between organisms with a nucleus (eukaryotes) and those without (prokaryotes/Monera).

From Morphology to Modern Taxonomy

The significance of Haeckel’s tree extends beyond history; it underpins the logic used in medical science today. By attempting to group organisms based on phylogeny—their evolutionary development and diversification—Haeckel set the stage for understanding biological complexity. In the image, the distinct branches of Plantae, Animalia, and Protista rise from the root. This visual separation helps explain fundamental physiological differences. For example, animal cells lack cell walls and rely on external food sources, while plant cells possess rigid walls and produce their own food. Understanding these cellular differences is vital in pharmacology; for instance, antifungal medications target cell wall components that human cells do not possess.

The area labeled “Moneres” at the root is particularly significant for medical microbiology. Haeckel later defined this as the kingdom Monera to classify unicellular organisms lacking a nucleus. Today, we understand these as prokaryotic organisms, primarily bacteria and archaea. The distinction between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (those with a nucleus, like plants, animals, and protists) is the basis for antibiotic therapy. Antibiotics are designed to disrupt the machinery of prokaryotic bacteria without harming the eukaryotic cells of the human patient. Without the taxonomic distinction initiated by early biologists like Haeckel, the targeted treatment of infectious diseases would be conceptually impossible.

Furthermore, the inclusion of Protista highlights a group of organisms that remain medically relevant. Many parasitic diseases, such as malaria (caused by Plasmodium) and amoebic dysentery, are caused by organisms that fall into this category. In Haeckel’s time, the exact nature of these pathogens was just beginning to be understood. His classification system provided a way to study these entities not as “failed” plants or animals, but as a distinct group with its own evolutionary trajectory and biological behaviors.

The Legacy of the Three-Kingdom System

While modern science has expanded beyond Haeckel’s three (and later four) kingdoms into a three-domain system (Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya), his fundamental approach remains valid. The “Tree of Life” serves as a reminder that biological diversity is the result of billions of years of adaptation and speciation. The “Radix communis” or common root emphasizes that at the biochemical level, all life shares the same basic DNA and RNA machinery.

In contemporary medical research, taxonomy is used to track the mutation of viruses and the spread of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Just as Haeckel traced branches back to a trunk, modern epidemiologists trace strains of viruses back to their source to understand outbreaks. The visual language of the tree allows complex genetic data to be interpreted and understood, facilitating the development of vaccines and treatments that are specific to the biological makeup of the pathogen.

Conclusion

Ernst Haeckel’s 1866 “Tree of Life” is more than an artistic rendering; it is a foundational document in the history of science that bridged the gap between Darwinian evolution and systematic classification. By visualizing the relationships between Plantae, Protista, and Animalia, and acknowledging the existence of simpler forms like Monera, Haeckel provided the intellectual architecture necessary for the development of modern biology and medicine. His work reminds us that understanding the evolutionary history of life is essential for understanding the cellular and genetic mechanisms that govern health and disease today.