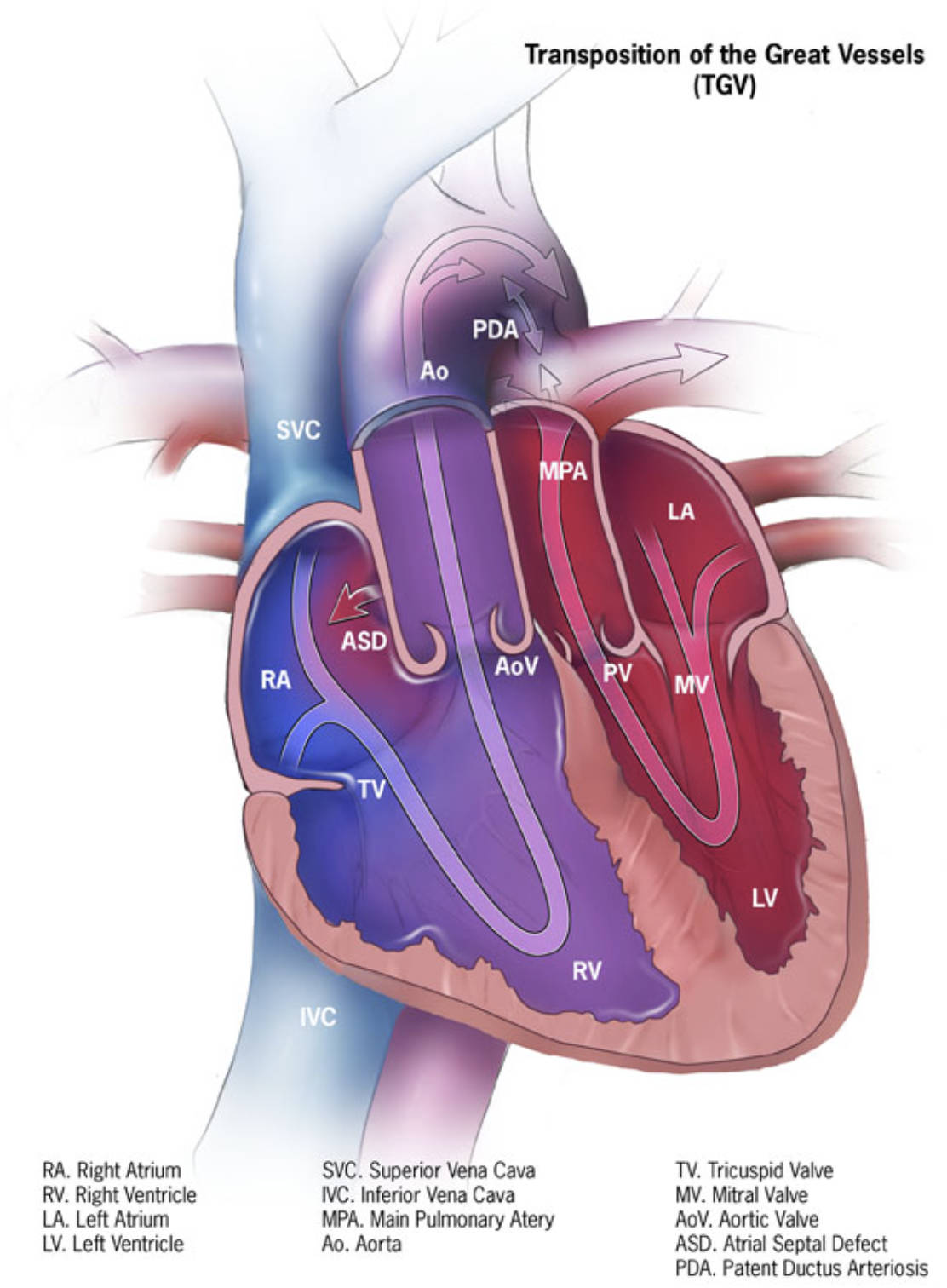

Dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries (d-TGA) is a critical congenital heart defect in which the two main arteries leaving the heart—the aorta and the pulmonary artery—are reversed (transposed). This anatomical anomaly disrupts the normal blood flow circulation, creating two parallel circuits rather than the standard continuous loop, which prevents oxygenated blood from effectively reaching the body. This article provides a detailed anatomical analysis of the condition based on the provided diagram, explaining the abnormal connections and the compensatory mechanisms, such as septal defects, that are essential for survival in the neonatal period.

Anatomical Labels and Explanations

PDA (Patent Ductus Arteriosus): This is a persistent blood vessel connecting the aorta and the main pulmonary artery. In d-TGA, this structure is vital for survival as it allows oxygenated blood from the pulmonary circulation to mix with the deoxygenated blood in the systemic circulation.

Ao (Aorta): The aorta is the body’s main artery, but in this diagram of d-TGA, it abnormally arises from the right ventricle instead of the left. Consequently, it carries deoxygenated (blue) blood directly back to the body without passing through the lungs.

SVC (Superior Vena Cava): This large vein collects deoxygenated blood from the head, neck, and upper extremities. It delivers this blood into the right atrium, functioning normally in terms of inflow but feeding into a compromised outflow track.

MPA (Main Pulmonary Artery): This vessel transports blood to the lungs for oxygenation, but in d-TGA, it incorrectly originates from the left ventricle. This causes oxygen-rich blood returning from the lungs to be pumped right back to the lungs, creating a futile loop.

LA (Left Atrium): This chamber receives oxygenated blood returning from the lungs via the pulmonary veins. In this pathology, the blood flows from the LA into the left ventricle and is immediately sent back to the lungs via the transposed pulmonary artery.

ASD (Atrial Septal Defect): This is a hole in the septum (wall) separating the left and right atria. This defect is clinically significant in d-TGA because it facilitates the mixing of oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood, improving the oxygen saturation of blood pumped to the body.

AoV (Aortic Valve): This valve regulates blood flow from the ventricle into the aorta. In this transposed heart, it sits between the right ventricle and the aorta, rather than its normal position on the left side.

PV (Pulmonary Valve): This valve controls blood flow into the pulmonary artery. In the diagram, it is located between the left ventricle and the main pulmonary artery, preventing backflow into the ventricle after contraction.

MV (Mitral Valve): Located between the left atrium and the left ventricle, this valve allows oxygenated blood to fill the ventricle. Its function remains mechanically normal, but the destination of the blood it passes is pathological.

RA (Right Atrium): This chamber receives deoxygenated blood from the body via the vena cavae. It pumps this blood through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle.

TV (Tricuspid Valve): This valve separates the right atrium from the right ventricle. It ensures one-way blood flow into the ventricle, which, in this defect, incorrectly pumps into the systemic circulation.

LV (Left Ventricle): This is typically the high-pressure pumping chamber for the body, but here it is connected to the low-pressure pulmonary circulation. It pumps oxygenated blood back to the lungs via the pulmonary artery.

RV (Right Ventricle): This chamber normally pumps blood to the lungs, but in d-TGA, it is connected to the aorta. It is forced to pump deoxygenated blood to the entire body, effectively acting as the systemic pump.

IVC (Inferior Vena Cava): This large vein carries deoxygenated blood from the lower body and abdomen to the right atrium. Like the SVC, it delivers blood to the right side of the heart, which then recirculates it to the body without oxygenation.

The Hemodynamics of Transposition

The image depicts a classic case of d-TGA, a cyanotic heart defect that accounts for a significant percentage of cardiac anomalies in newborns. In a structurally normal heart, blood flows in a series: body to heart, heart to lungs, lungs to heart, and heart back to body. However, in d-TGA, the connections are switched. The aorta is attached to the right ventricle, and the pulmonary artery is attached to the left ventricle. This creates two separate, parallel circulatory loops.

In the first loop, oxygen-poor blood from the body enters the right atrium and ventricle and is pumped directly back to the body through the aorta. In the second loop, oxygen-rich blood from the lungs enters the left atrium and ventricle and is pumped back to the lungs through the pulmonary artery. Without intervention or specific anatomical features allowing for “mixing,” this condition is incompatible with life because the body’s tissues are deprived of oxygen.

The diagram highlights specific structures—the ASD and PDA—that act as lifelines. These connections allow the two isolated circulatory loops to communicate. The mixing of blood through these shunts ensures that at least some oxygenated blood reaches the systemic circulation. This is why medical professionals often administer prostaglandins to a newborn with d-TGA to keep the ductus arteriosus open until surgery can be performed.

Key physiological challenges in d-TGA include:

- Cyanosis: A bluish tint to the skin due to low oxygen saturation in the arterial blood.

- Hypoxia: Insufficient oxygen delivery to vital organs and tissues.

- Ventricular Mismatch: The right ventricle is forced to pump against high systemic pressure, which it is not anatomically designed to handle long-term.

- Pulmonary Vascular changes: The high pressure from the left ventricle pumping into the lungs can eventually damage pulmonary vessels.

Clinical Presentation and Surgical Correction

Dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries is a medical emergency usually diagnosed shortly after birth or prenatally via fetal echocardiogram. The hallmark sign is profound cyanosis that does not improve with the administration of supplemental oxygen. Because the oxygenated blood is trapped in the pulmonary loop, the baby will appear blue regardless of how much oxygen is breathed in. This paradox is a key diagnostic clue for neonatologists. If the natural shunts (ASD or PDA) begin to close, the infant’s condition will deteriorate rapidly, leading to severe acidosis and cardiovascular collapse.

The standard treatment for d-TGA is the Arterial Switch Operation (ASO). This complex open-heart surgery is typically performed within the first weeks of life. During the procedure, the surgeon detaches the aorta and pulmonary arteries from their incorrect origins and reattaches them to the correct ventricles. Crucially, the coronary arteries, which supply blood to the heart muscle itself, must also be meticulously transferred to the new aortic position. This restores normal “series” circulation, allowing the left ventricle to pump oxygenated blood to the body and the right ventricle to pump deoxygenated blood to the lungs.

Before surgery, stabilization is key. If the mixing of blood is insufficient, a procedure known as a balloon atrial septostomy (Rashkind procedure) may be performed. This involves threading a catheter into the heart to enlarge the Atrial Septal Defect (ASD), facilitating better mixing of oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood. The diagram above illustrates the anatomy prior to surgical correction, showcasing why these inter-atrial and ductal communications are so vital for the infant’s temporary survival.

Conclusion

The diagram of Transposition of the Great Vessels serves as a crucial educational tool for understanding one of the most severe congenital heart defects. It visually demonstrates the dangerous isolation of the pulmonary and systemic circulations and highlights the importance of the PDA and ASD as temporary survival mechanisms. Through advances in medical imaging and surgical techniques like the arterial switch, the prognosis for infants born with this once-fatal condition has improved dramatically, allowing most to live healthy, active lives.