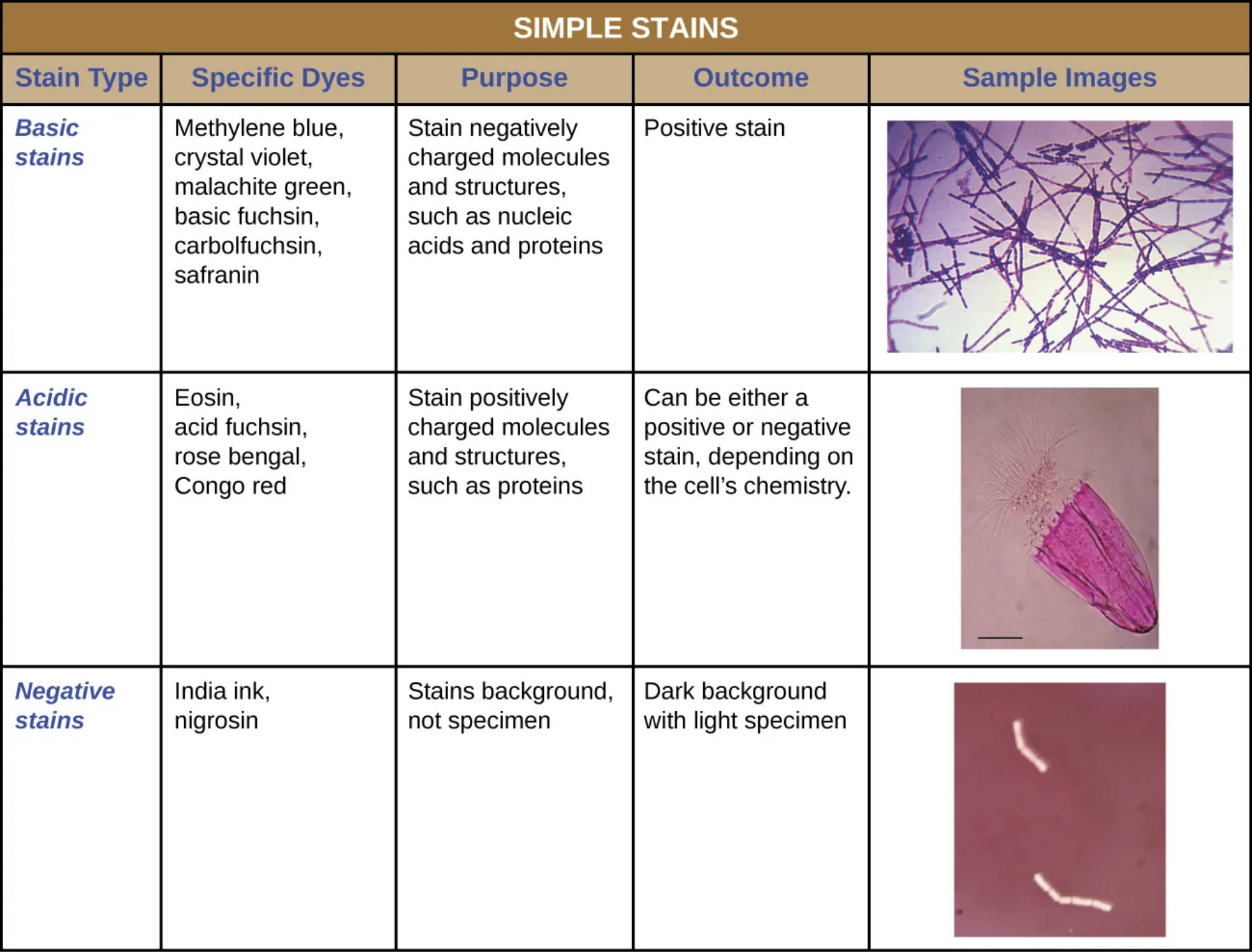

Microscopic analysis is a cornerstone of medical diagnostics, allowing laboratory professionals to visualize microorganisms that are otherwise invisible to the naked eye. Because most bacterial cells are transparent in their natural state, simple staining techniques are employed to create contrast between the organism and its background. The following guide details the classification of simple stains—including basic, acidic, and negative stains—explaining their chemical mechanisms, specific dyes, and outcomes used in clinical laboratories to identify cell morphology and arrangement.

Basic stains: These stains utilize positively charged dyes, known as cationic chromophores, which include common laboratory reagents such as methylene blue, crystal violet, malachite green, and safranin. Because bacterial cell walls carry a net negative charge due to their phospholipid and peptidoglycan composition, these positive dyes are electrostatically attracted to the cell, resulting in a stained specimen against a clear background.

Acidic stains: These preparations employ negatively charged dyes, or anionic chromophores, such as eosin, acid fuchsin, rose bengal, and Congo red. These dyes are repelled by the negatively charged bacterial surface but bind readily to positively charged cellular components, making them useful in histology for staining cytoplasmic proteins or specific tissue structures.

Negative stains: This technique uses colloidal dyes like India ink or nigrosin to darken the background rather than the specimen itself. Because the chromophores in these dyes are negatively charged, they are repelled by the bacterial cell wall, creating a silhouette effect where the organism appears as a clear, light shape against a dark field, which is particularly useful for visualizing delicate structures like capsules.

The Fundamentals of Microscopic Contrast

In the field of clinical microbiology, the ability to rapidly determine the presence and shape of bacteria is often the first step in diagnosing an infection. Fresh bacterial cultures are primarily water, meaning they lack the optical density required to stand out against the bright light of a microscope. Staining solves this issue by chemically adhering colored molecules to the biological specimen. While differential stains (like the Gram stain) distinguish between bacterial types, simple stains use a single dye to highlight the entire microorganism, allowing for the immediate assessment of cell size, shape, and arrangement.

The interaction between a dye and a cell is fundamentally a chemical reaction based on pH and ionic charge. A stain consists of a solvent (usually water or ethanol) and a colored molecule called a chromophore. If the chromophore is a positive ion, the stain is classified as basic; if it is a negative ion, it is acidic. This distinction dictates whether the dye will penetrate the cell wall and stain the internal components or settle around the exterior of the cell.

Understanding which stain to use is critical for accurate observation. For instance, heat fixation—a process used to adhere bacteria to a slide—can sometimes distort cell shape. Techniques that do not require heat, such as negative staining, are therefore preferred when the precise morphology or the presence of a delicate capsule needs to be preserved.

Key applications of simple staining in medical diagnostics include:

- Morphological Identification: determining if bacteria are spheres (cocci), rods (bacilli), or spirals (spirillum).

- Arrangement Analysis: observing if cells group in chains (streptococci), clusters (staphylococci), or pairs (diplococci).

- Capsule Visualization: detecting protective outer layers that may indicate increased virulence.

- Rapid Screening: providing a quick “yes or no” regarding the presence of bacteria in sterile body fluids.

Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Relevance

The most frequently used simple stains in a general microbiology setting are basic stains. Dyes like methylene blue or crystal violet dissociate into ions when dissolved. The positively charged color ion is strongly attracted to the negative charge of nucleic acids and bacterial cell walls. This affinity ensures that the cell itself becomes deeply colored. In a clinical context, a technician might use a simple stain on a sample from a wound or fluid to quickly confirm bacterial presence before proceeding with more complex differential stains or cultures. This rapid feedback can be crucial in acute care settings where preliminary data helps guide initial empirical therapy.

Conversely, negative staining holds a unique place in diagnostic microbiology, particularly for identifying encapsulated pathogens. A classic medical example is the detection of Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungal pathogen that causes meningitis, especially in immunocompromised patients. The organism possesses a thick, gelatinous capsule that repels most stains and can be destroyed by heat fixation. By using India ink (a negative stain), the background is darkened, and the yeast cell and its halo-like capsule stand out as a clear exclusion zone. This method allows for the diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis directly from cerebrospinal fluid.

Acidic stains are less common in pure bacteriology but are vital in histology and cytology—the study of tissues and cells. In these fields, dyes like eosin are often paired with basic dyes (like hematoxylin) to create H&E stains, the gold standard for diagnosing cancers and inflammatory conditions in tissue biopsies. The acidic dye binds to positively charged amino acids in the cytoplasm and connective tissue fibers, turning them pink or red, which helps pathologists differentiate between muscle, red blood cells, and collagen.

Conclusion

The table of simple stains represents the foundational toolkit of the distinct microscopic world. Whether utilizing the electrostatic attraction of basic dyes to reveal bacterial chains or employing the repulsion of negative stains to highlight virulence factors like capsules, these techniques are essential for accurate biological visualization. Mastering the selection and application of these dyes ensures that medical professionals can obtain the high-quality images necessary for reliable diagnosis and subsequent patient care.