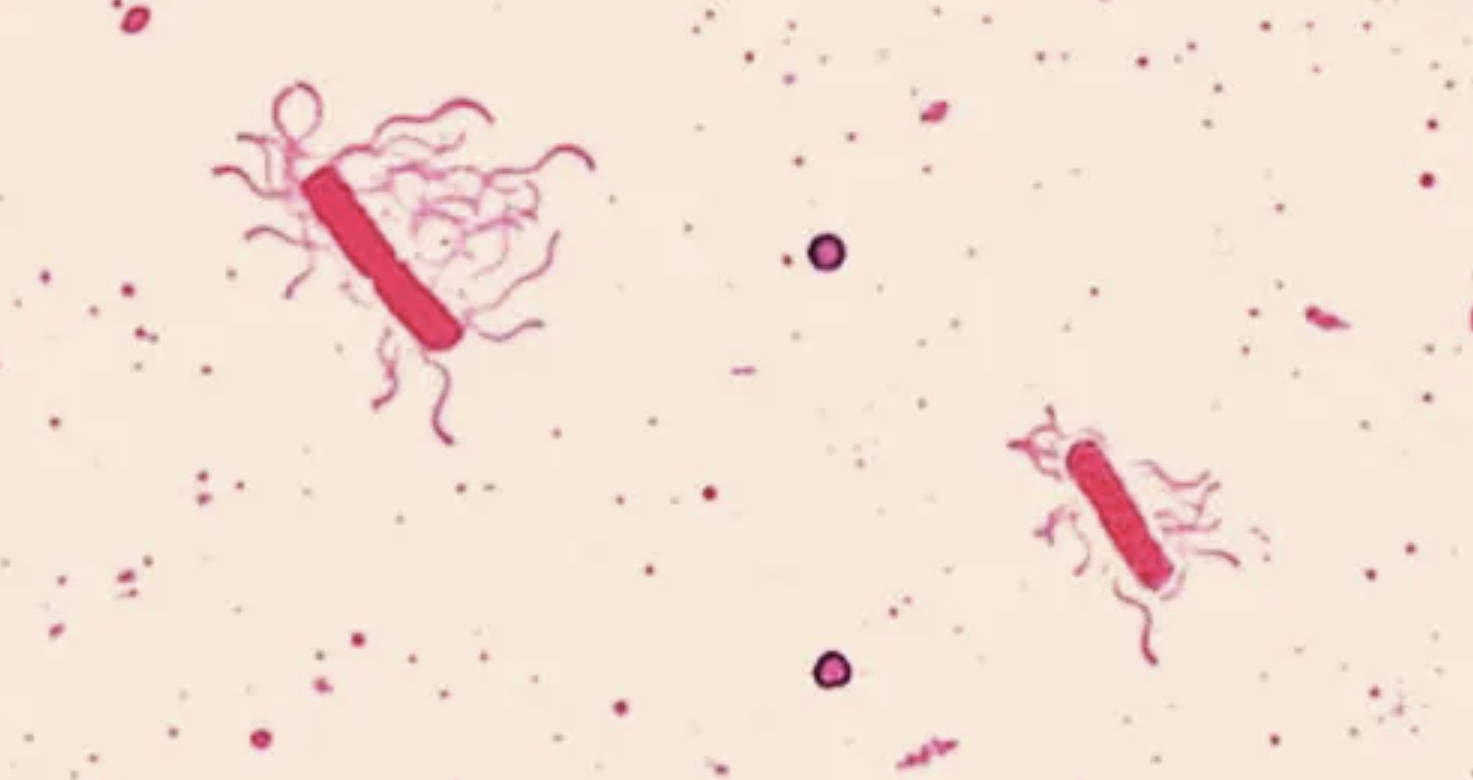

This microscopic analysis highlights a flagella stain of Bacillus cereus, a Gram-positive bacterium widely recognized for its role in gastrointestinal diseases. The image reveals the distinct morphological features of the organism, specifically focusing on the motile structures that allow the bacteria to navigate their environment. Understanding the physical characteristics of this pathogen is essential for microbiologists and healthcare professionals when diagnosing the source of foodborne outbreaks and implementing effective food safety protocols.

Morphological Characteristics and Motility

The image displays a specialized staining technique designed to visualize bacterial flagella, which are otherwise too thin to be seen with standard light microscopy methods like the Gram stain. In this preparation, a mordant has been used to coat the flagella, increasing their diameter and allowing them to absorb the stain. The central structures are the rod-shaped vegetative cells, typical of the genus Bacillus. Radiating from these cells are numerous wavy, hair-like appendages known as flagella. Their arrangement is described as peritrichous, meaning the flagella are distributed over the entire surface of the bacterial cell.

This flagella stain is critical for differential diagnosis in the laboratory. While many bacteria are rod-shaped, the presence and arrangement of flagella provide key taxonomic clues. For Bacillus cereus, motility is a vital survival mechanism. It allows the bacterium to move toward nutrients (chemotaxis) and find optimal environments for colonization. In a host environment, this motility can aid the bacteria in penetrating the mucous lining of the intestines, facilitating the delivery of toxins that cause illness.

The presence of these locomotor structures indicates that the bacteria are in a vegetative, metabolically active state. While Bacillus species are famous for forming dormant endospores to survive harsh conditions, the expression of flagella suggests the organism is currently in an environment supporting growth and movement. This distinction is important for food safety, as the vegetative cells are the active producers of the enterotoxins responsible for symptoms in humans.

Key features visible in this microscopic preparation include:

- Rod-shaped morphology: The cylindrical structure characteristic of bacilli bacteria.

- Peritrichous flagellation: Multiple flagella emerging from all sides of the cell body.

- Vegetative state: The active, non-spore form of the bacterium capable of reproduction and motility.

- Binary Fission: Some cells may appear linked in chains or pairs, indicating recent division.

Clinical Implications: Bacillus Cereus and Foodborne Illness

Bacillus cereus is a significant pathogen in the context of public health, primarily known for causing two distinct types of foodborne illness. The bacterium is ubiquitous in the environment, found naturally in soil and vegetation, which leads to the frequent contamination of various food products. The pathology of the disease depends largely on which toxin is produced and ingested.

The first clinical presentation is the emetic (vomiting) syndrome, often colloquially referred to as “fried rice syndrome.” This condition is caused by the ingestion of cereulide, a heat-stable toxin produced by the bacteria while growing in food. This form of intoxication is frequently associated with starchy foods like rice or pasta that have been cooked and then left at room temperature for extended periods. Because the toxin is pre-formed in the food and resistant to heat, reheating the food does not neutralize the threat. Symptoms, including nausea and vomiting, typically appear rapidly, often within 1 to 5 hours after consumption.

The second presentation is the diarrheal syndrome, which mimics the symptoms of Clostridium perfringens infection. This form occurs when viable Bacillus cereus cells or spores are ingested and subsequently produce enterotoxins within the small intestine. This type is commonly linked to meats, vegetables, and sauces. The onset is slower, usually occurring 6 to 15 hours after eating, and is characterized by watery diarrhea and abdominal cramps. While both forms of the illness are generally self-limiting and resolve within 24 to 48 hours, they can pose serious risks to immunocompromised individuals, requiring medical attention to manage dehydration.

Conclusion

The visualization of Bacillus cereus through flagella staining provides valuable insight into the biological machinery of this common pathogen. By identifying the peritrichous arrangement of the flagella, laboratory professionals can better classify the organism and understand its capability for motility and colonization. Furthermore, recognizing the duality of Bacillus cereus as both an environmental organism and a producer of potent toxins reinforces the importance of strict hygiene and temperature control in food preparation to prevent widespread outbreaks of gastroenteritis.