Microbiology relies heavily on the ability to classify bacteria quickly and accurately, and the Gram stain remains the gold standard for this initial identification. This differential staining technique allows laboratory professionals to categorize bacteria into two distinct groups—Gram-positive and Gram-negative—based on the structural differences in their cell walls. By understanding this four-step process, medical providers can rapidly narrow down potential pathogens and determine appropriate empirical antibiotic treatments before more specific culture results are available.

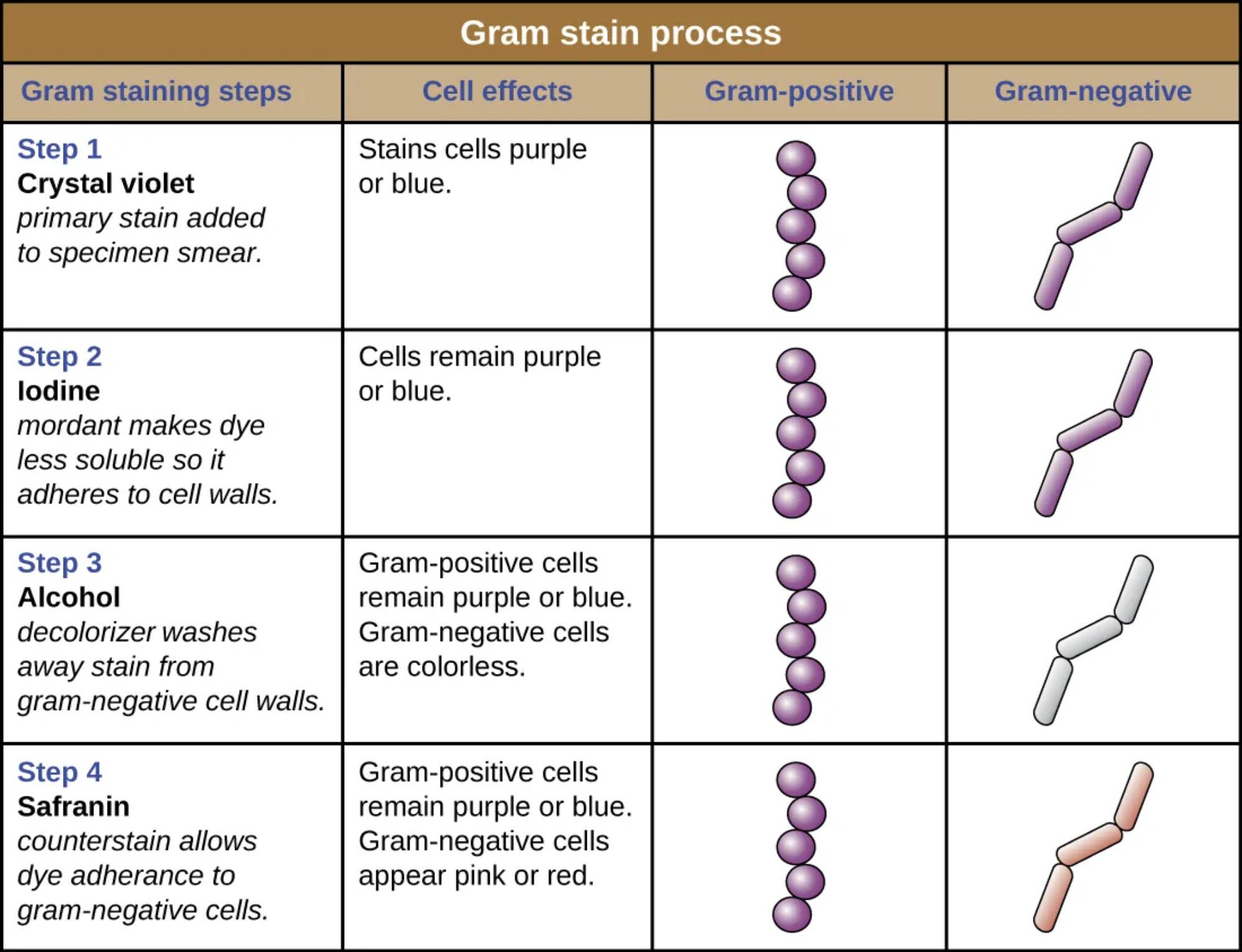

Step 1 Crystal violet: This is the primary stain applied to the bacterial specimen smear. During this initial phase, the basic dye penetrates the cell wall of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, staining all cells a deep purple or blue color regardless of their classification.

Step 2 Iodine: Following the primary stain, iodine is added to the smear to act as a mordant, a substance that sets the dye. The iodine binds with the crystal violet to form a large, insoluble crystal violet-iodine (CV-I) complex within the cell, ensuring that the dye adheres strongly to the cell walls and keeping both cell types purple.

Step 3 Alcohol: This decolorization step is the most critical part of the differential process and typically uses ethanol or acetone. The alcohol washes the crystal violet-iodine complex out of the thinner walls of Gram-negative bacteria, rendering them colorless, while the thick cell walls of Gram-positive bacteria dehydrate and trap the purple dye inside.

Step 4 Safranin: As the final counterstain, safranin is applied to the smear to color the now-invisible Gram-negative cells. Because Gram-positive cells are already saturated with the dark purple dye, the lighter pink safranin does not affect their appearance, but it stains the colorless Gram-negative cells pink or red so they can be visualized under a microscope.

The Significance of Differential Staining in Microbiology

The Gram stain, developed by Danish bacteriologist Hans Christian Gram in 1884, is arguably the most important staining technique in the field of bacteriology. Unlike simple stains that use a single dye to reveal cell shape and arrangement, differential staining utilizes multiple chemical reagents to highlight biological differences between organisms. The process takes advantage of the chemical and physical properties of bacterial cell walls, allowing clinicians to distinguish between two major groups of bacteria. This distinction is not merely cosmetic; it reflects fundamental differences in bacterial physiology that dictate how an organism behaves, causes disease, and responds to medical treatment.

The procedure requires precision, particularly during the decolorization stage. If the alcohol is left on too long, it can remove the dye from Gram-positive cells (over-decolorization), making them appear Gram-negative. Conversely, if the alcohol is not applied long enough (under-decolorization), Gram-negative cells may retain the purple dye. A correctly performed Gram stain provides immediate data regarding the bacterial burden in a sample and the morphology of the invading pathogen (e.g., cocci vs. rods).

The clinical utility of this process cannot be overstated. When a patient presents with a severe infection, such as sepsis or meningitis, waiting days for a final culture result is often not an option. A Gram stain provides a result within minutes. Key benefits of this technique include:

- Rapid Diagnosis: It allows for immediate visualization of bacteria in sterile body fluids like cerebrospinal fluid or synovial fluid.

- Antibiotic Guidance: It helps physicians choose the correct spectrum of antibiotics early in treatment.

- Quality Control: It assesses the quality of clinical specimens; for example, a sputum sample with many epithelial cells and few bacteria may indicate saliva contamination rather than a deep lung infection.

- Morphological Identification: It reveals cellular arrangements, such as clusters (Staphylococci) or chains (Streptococci).

Physiological Differences in Bacterial Cell Walls

To truly understand the Gram stain, one must look at the molecular architecture of the bacterial cell wall. The primary component involved in this staining reaction is peptidoglycan, a rigid mesh-like polymer consisting of sugars and amino acids that provides structural support to the cell. The thickness and arrangement of this peptidoglycan layer determine whether an organism is Gram-positive or Gram-negative.

In Gram-positive bacteria, the cell wall consists of a thick, multi-layered coat of peptidoglycan situated outside the plasma membrane. This layer is rich in teichoic acids, which are negatively charged and help regulate the passage of ions. When the crystal violet-iodine complex forms during the staining process, it becomes trapped deep within this thick meshwork. The subsequent application of alcohol dehydrates the peptidoglycan, causing it to shrink and tighten, which effectively locks the purple dye inside the cell. Consequently, these bacteria retain the primary stain and appear purple under the microscope.

In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria possess a much more complex, yet physically thinner, cell wall structure. They have only a thin layer of peptidoglycan located in the periplasmic space between the inner plasma membrane and an outer membrane. This outer membrane is unique to Gram-negative organisms and contains lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and porins. During the decolorization step, the alcohol dissolves the lipid-rich outer membrane and damages the thin peptidoglycan layer. This increases the porosity of the cell wall, allowing the crystal violet-iodine complex to wash out easily. Once the primary stain is removed, the cells are colorless until the safranin counterstain is applied, turning them pink or red.

Conclusion

The Gram stain remains a cornerstone of diagnostic microbiology, bridging the gap between basic cellular anatomy and critical medical decision-making. By visualizing the differences in cell wall composition, this simple yet elegant four-step process empowers healthcare teams to categorize pathogens rapidly. Whether identifying a Gram-positive infection like Staphylococcus aureus or a Gram-negative issue like Escherichia coli, the visual cues provided by crystal violet, iodine, alcohol, and safranin are essential for initiating life-saving therapies and understanding the microscopic nature of infectious diseases.