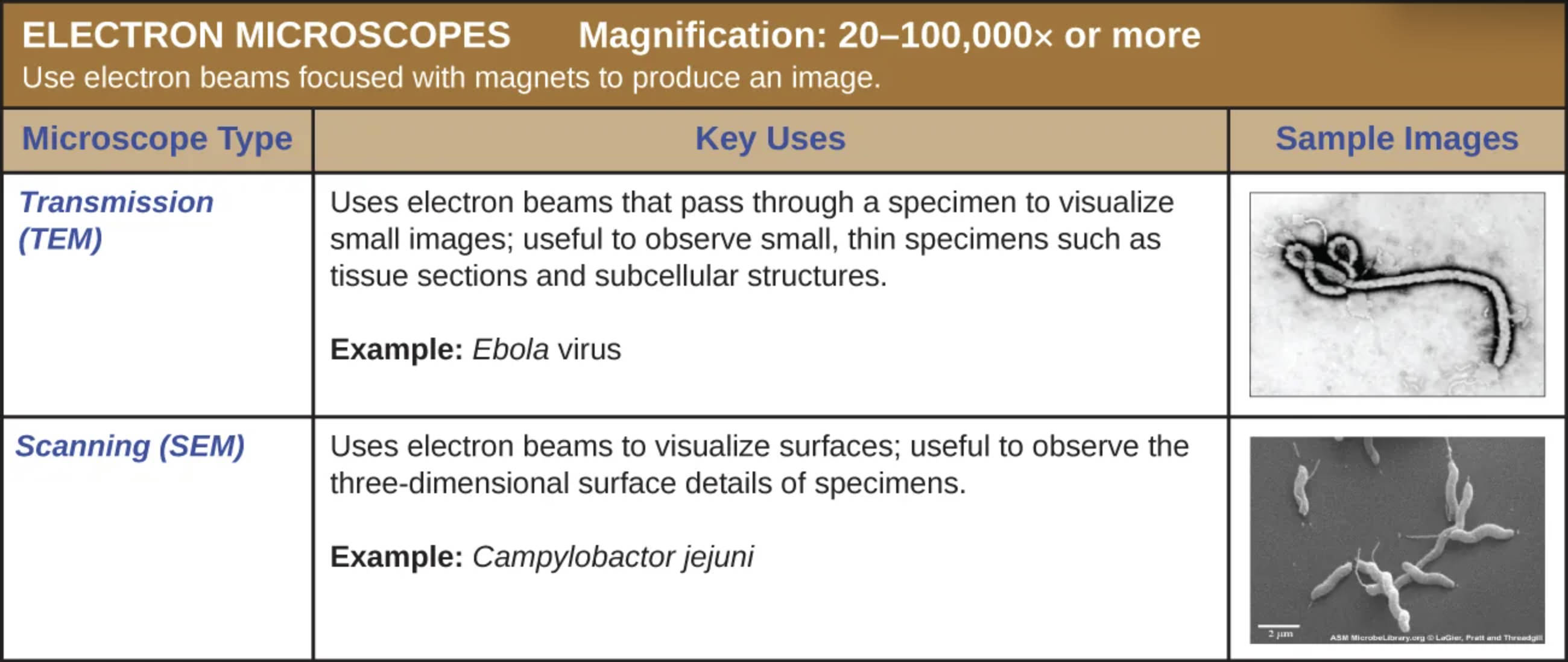

Electron microscopy represents a pinnacle of medical imaging technology, allowing scientists to visualize biological structures far beyond the capabilities of standard light microscopes. By utilizing focused electron beams rather than photons, researchers can examine everything from the internal components of a virus to the surface texture of bacteria with magnification levels ranging from 20 to over 100,000 times. This guide details the specific functions of Transmission and Scanning Electron Microscopes, highlighting their critical roles in pathogen identification and disease research.

Transmission (TEM): This technique utilizes electron beams that pass directly through a specially prepared, ultra-thin specimen to visualize minute internal details. It is particularly useful for observing subcellular structures, such as organelles or viral cores, as demonstrated by the image of the Ebola virus, where the internal density and characteristic shape are clearly visible.

Scanning (SEM): This method employs electron beams to scan back and forth across the surface of a specimen, creating a detailed image based on the electrons bouncing off the object. It is exceptionally useful for observing the three-dimensional surface topography of cells, as seen in the image of Campylobacter jejuni, where the external shape and flagella are rendered in high relief.

The Power of Electron Beams in Microbiology

The advent of electron microscopy revolutionized the field of microbiology and pathology by overcoming the physical limitations of light microscopy. While traditional light microscopes are limited by the wavelength of visible light—capping their effective magnification at around 1000x—electron microscopes use a beam of electrons with a much shorter wavelength. This allows for a dramatic increase in resolution and magnification, enabling scientists to see structures measured in nanometers rather than micrometers.

The fundamental difference between these microscopes lies in how the electron beam interacts with the sample. In these systems, electromagnetic lenses (magnets) are used to focus the beam, much like glass lenses focus light. Because electrons are easily scattered by air molecules, both Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) require the samples to be viewed inside a vacuum. This requirement means that living specimens cannot be observed; samples must be fixed, dehydrated, and often coated with heavy metals to improve contrast and conductivity.

Despite the inability to view live processes, the structural data obtained is invaluable. Medical researchers rely on these tools to classify new pathogens, understand how viruses enter cells, and study the effects of antibiotics on bacterial cell walls. The choice between TEM and SEM depends entirely on the diagnostic question at hand: does the researcher need to see inside the cell or look at its exterior?

Key distinctions and capabilities of these systems include:

- Resolution Power: TEM offers the highest resolution, capable of distinguishing atoms, while SEM provides excellent depth of field for 3D imaging.

- Sample Preparation: TEM requires extremely thin slicing (ultramicrotomy), whereas SEM requires the sample to be conductive, usually achieved by sputter-coating with gold or platinum.

- Visual Output: TEM produces 2D projection images, while SEM produces images that appear three-dimensional.

- Application: TEM is standard for viral diagnostics; SEM is often used to study bacterial biofilms and tissue surfaces.

Clinical Case Study: The Ebola Virus (TEM Application)

The TEM image provided illustrates the Ebola virus, a member of the Filoviridae family. This pathogen is responsible for Ebola Virus Disease (EVD), a severe and often fatal illness in humans. The virus is distinct in its appearance; under a transmission electron microscope, it appears as a long, filamentous structure that can be coiled, toroid, or branched—often described as looking like a shepherd’s crook or a loop. This unique morphology is key to its identification during outbreaks.

Ebola is a viral hemorrhagic fever that disrupts the body’s immune system and causes damage to blood vessels and coagulation mechanisms. Following an incubation period of 2 to 21 days, patients typically present with sudden fever, fatigue, muscle pain, and sore throat. As the disease progresses, it leads to vomiting, diarrhea, impaired kidney and liver function, and in some cases, both internal and external bleeding. The virus is transmitted to people from wild animals and spreads in the human population through human-to-human transmission via direct contact with the blood, secretions, organs, or other bodily fluids of infected people, and with surfaces and materials (e.g., bedding, clothing) contaminated with these fluids.

Clinical Case Study: Campylobacter jejuni (SEM Application)

The SEM image provided displays Campylobacter jejuni, a helical-shaped bacterium that is one of the most common causes of foodborne gastroenteritis worldwide. The scanning electron microscope is ideal for viewing this organism because it clearly reveals the bacterium’s corkscrew or spiral shape and its polar flagella (tail-like structures), which provide the motility needed to penetrate the mucus lining of the human intestine.

Infection with this bacterium, known as Campylobacteriosis, typically results from eating raw or undercooked poultry, unpasteurized milk, or contaminated water. Symptoms usually onset within two to five days of exposure and include diarrhea (which is often bloody), abdominal cramping, fever, and nausea. While most patients recover with hydration and supportive care, C. jejuni is clinically significant because of its association with Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS). GBS is a rare autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks the nerves, potentially leading to paralysis. The detailed surface imaging provided by SEM helps researchers understand how the bacterium adheres to intestinal surfaces and how its physical structure contributes to its pathogenicity.

Conclusion

In the realm of medical science, the ability to visualize the unseen is the first step toward treatment and cure. Whether it is identifying the filiform shape of a deadly virus like Ebola using TEM or analyzing the spiral morphology of a foodborne bacteria like Campylobacter using SEM, electron microscopes serve as essential diagnostic and research tools. These technologies provide the high-resolution imagery necessary to understand the complex architecture of pathogens, ultimately guiding the development of vaccines, antibiotics, and public health protocols.