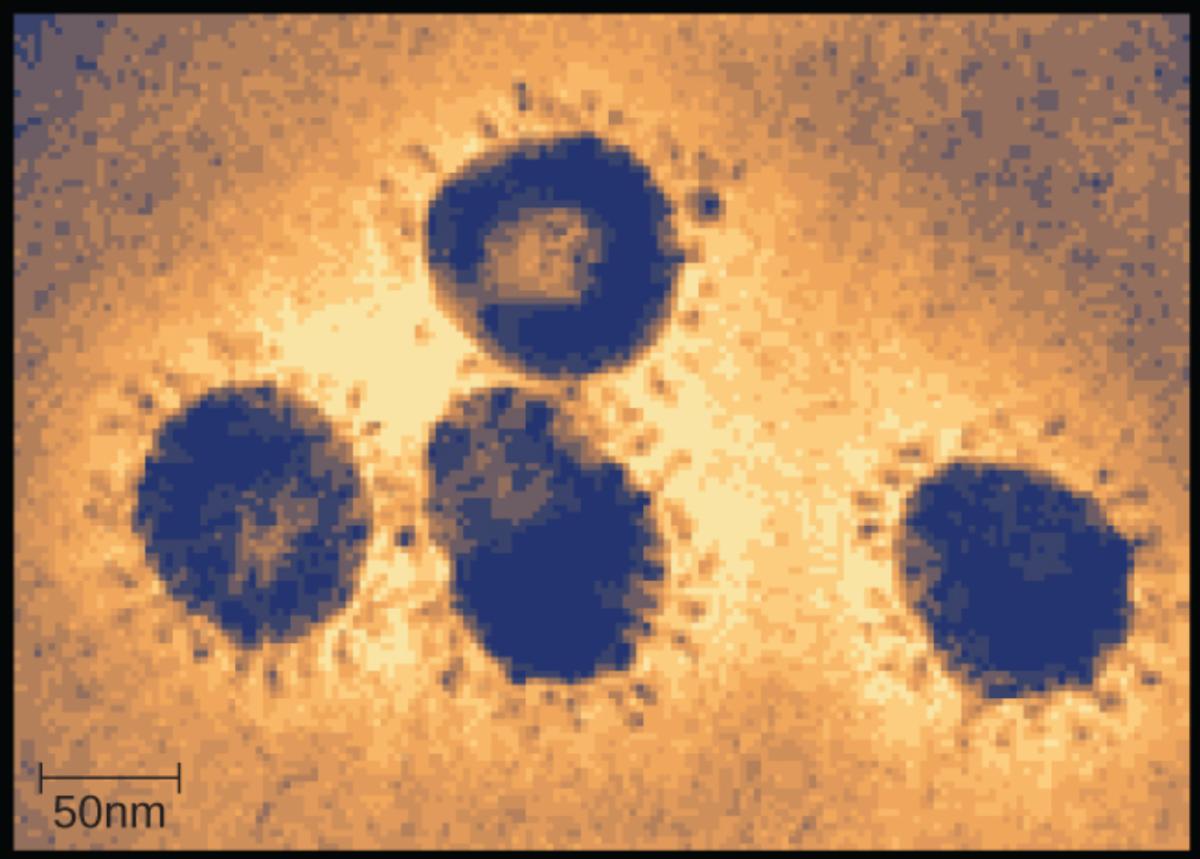

This transmission electron micrograph provides a detailed view of virions from the Coronavirus family, a group of RNA viruses responsible for a spectrum of human respiratory illnesses ranging from the common cold to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). The image highlights the distinctive structural features, particularly the halo of surface proteins, that define this viral classification and facilitate their mechanism of infection within the human host.

50nm: This scale bar represents 50 nanometers, providing a reference for the size of the viral particles shown in the field of view. Since the virions depicted are roughly two to three times the width of this bar, it indicates that individual coronavirus particles typically measure between 100 and 120 nanometers in diameter, which is consistent with the standard size for this viral family.

The Structural Biology of Coronaviruses

Coronaviruses are a large family of enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses. The name “coronavirus” is derived from the Latin word corona, meaning “crown” or “wreath.” This nomenclature is directly inspired by the appearance of the virus under a transmission electron microscope (TEM), as seen in the image above. The outer surface of the virus is studded with club-shaped glycoprotein projections that create a halo-like appearance, mimicking a solar corona.

These viruses are notoriously zoonotic, meaning they can be transmitted between animals and humans. While many coronaviruses circulate among animals such as bats, camels, and cattle without infecting humans, spillover events can occur. When these viruses jump the species barrier, they can adapt to human physiology, leading to varying degrees of disease severity. The structural integrity of the virus is maintained by four main structural proteins, which are encoded within its large genome.

The primary structural proteins that make up the coronavirus particle include:

- Spike (S) Protein: The large protrusions responsible for receptor binding and membrane fusion.

- Envelope (E) Protein: A small protein involved in the assembly and release of the virus.

- Membrane (M) Protein: The most abundant structural protein, which defines the shape of the viral envelope.

- Nucleocapsid (N) Protein: Bound to the RNA genome, forming the nucleocapsid complex inside the envelope.

Pathogenesis and Respiratory Syndromes

The most critical anatomical feature of the coronavirus, in terms of human pathology, is the spike protein. These proteins act as keys that unlock entry into human cells. For many coronaviruses, including the one responsible for SARS, the spike protein binds specifically to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor found on the surface of cells in the respiratory tract, lungs, heart, and kidneys. Once attached, the virus enters the cell and hijacks the host’s cellular machinery to replicate its genetic material.

While some human coronaviruses (such as HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43) are responsible for mild upper respiratory tract infections like the common cold, others cause severe disease. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), caused by SARS-CoV, emerged in 2002 and is characterized by fever, headache, and eventual respiratory distress. The virus induces a strong immune response, often leading to pneumonia and acute lung injury. The inflammation associated with SARS compromises the alveoli, preventing efficient oxygen exchange.

Another significant member of this family is the virus responsible for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). MERS-CoV, which was first identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012, utilizes a different receptor (DPP4) to enter cells. It is a zoonotic virus transmitted primarily from dromedary camels to humans. MERS is clinically distinct due to its rapid progression to respiratory failure and its high case-fatality rate, which is significantly higher than that of SARS or common influenza. Both SARS and MERS demonstrate the potential of this viral family to cause life-threatening systemic illness beyond simple respiratory irritation.

Conclusion

The transmission electron microscope image serves as a powerful diagnostic and educational tool, revealing the deceptively simple structure of a pathogen capable of causing global health crises. By visualizing the “crown” of spike proteins, researchers can better understand how these viruses attach to human cells, which is the first step in developing targeted vaccines and antiviral therapeutics. From the mild nuisance of a cold to the severe pathophysiology of SARS and MERS, understanding the morphology of the coronavirus is essential for modern virology and infectious disease management.