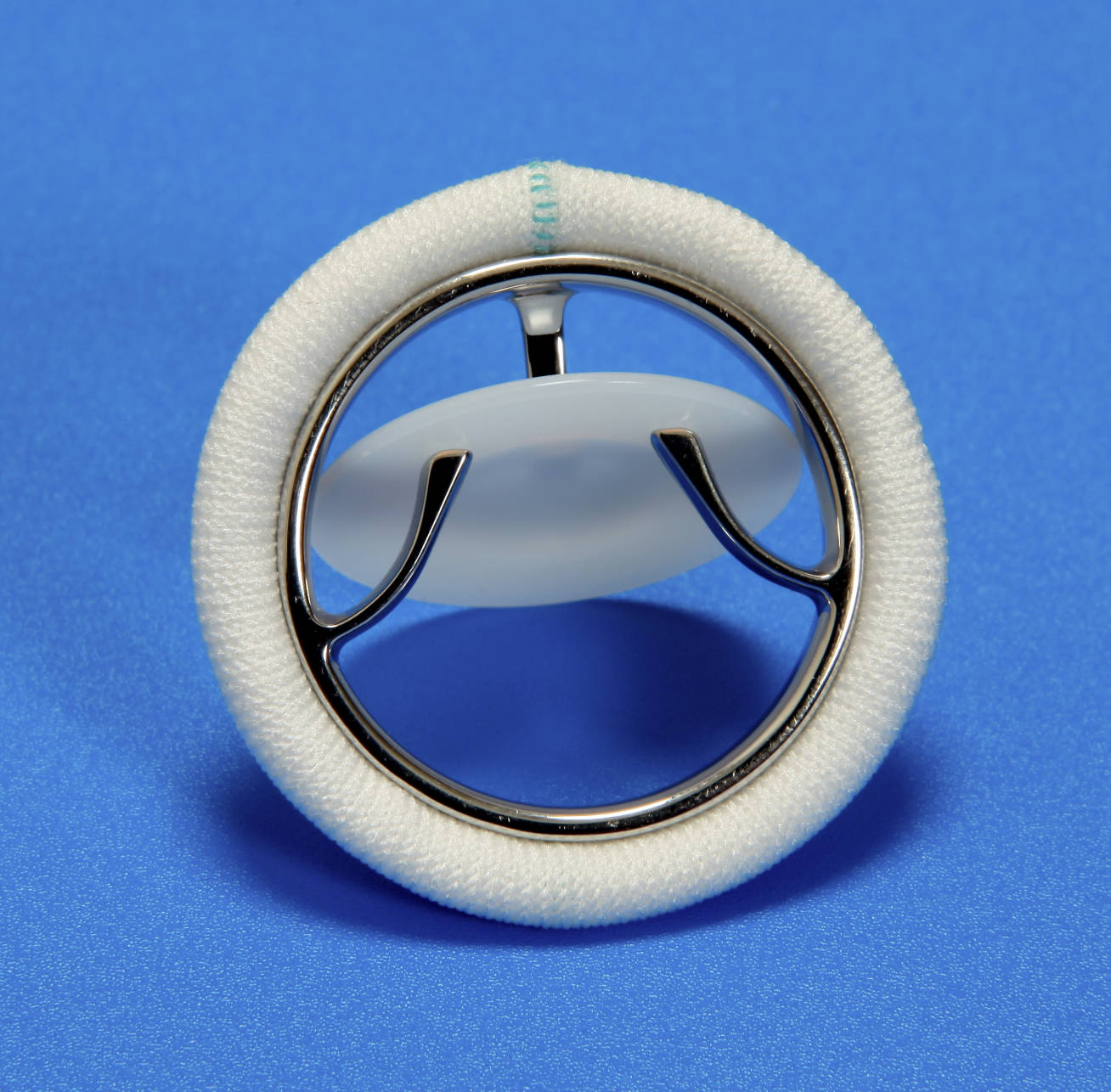

Mechanical heart valves represent a pivotal advancement in cardiac surgery, offering a durable solution for patients suffering from severe valvular dysfunction. The image provided illustrates a specific type of mechanical prosthesis known as a tilting-disc valve. Unlike biological valves derived from animal tissue, these devices are engineered from robust synthetic materials designed to last a lifetime. They function by mimicking the heart’s natural one-way flow, opening to allow blood passage and closing firmly to prevent backflow. This specific design improves upon earlier generations of valves by offering a lower profile and better hemodynamic performance, making it a critical tool in treating conditions like aortic stenosis or mitral regurgitation.

Anatomical Components of the Tilting-Disc Valve

Sewing Cuff: This is the white, fabric-like ring surrounding the outer perimeter of the valve, typically made from Dacron or polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). It serves as the anchor point for the surgeon, allowing them to suture the prosthetic device securely to the patient’s native heart tissue and promoting tissue ingrowth to prevent leaks around the valve (paravalvular leaks).

Valve Housing: The shiny, circular metal ring that frames the inner mechanism is known as the housing or stent. Usually constructed from biocompatible alloys like cobalt-chromium or titanium, this component provides structural integrity to the device and maintains the shape of the orifice through which blood flows.

Occluder Disc: The central, circular plate (often white or dark gray in appearance) is the mobile element of the valve, commonly made from ultra-durable pyrolytic carbon. This disc tilts open to a specific angle to allow blood to flow through during systole (for aortic valves) or diastole (for mitral valves) and pivots back to a flat, closed position to stop regurgitation.

Struts: The thin metal projections extending from the housing inward are the struts. These critical components act as a cage or stop mechanism, preventing the disc from dislodging and precisely controlling the angle at which the disc opens and closes to ensure optimal flow dynamics.

Mechanical Function and Hemodynamics

The tilting-disc valve was developed to overcome the hemodynamic limitations of earlier “ball-and-cage” mechanical valves. In this design, a free-floating disc is held in place by metallic struts. When blood pressure builds up behind the valve, the force tilts the disc open, creating two distinct openings for blood flow: a major orifice and a minor orifice. This separation reduces the resistance to blood flow compared to older designs, allowing the heart to pump more efficiently without generating excessive pressure gradients.

This valve type is renowned for its extreme durability. Because it is entirely synthetic, it does not degrade over time like biological tissue valves, which may calcify or tear after 10 to 15 years. This makes the tilting-disc valve an ideal choice for younger patients who require a long-term solution and wish to avoid re-operation. However, the interaction between blood cells and the hard surfaces of the valve—specifically the hinge points and the disc—can activate the body’s clotting mechanisms.

To ensure the longevity of the patient and the proper function of the device, strict medical management is required post-surgery. The mechanical nature of the valve generates high shear stress on blood components, which necessitates lifelong medication to prevent thrombus formation.

- Key characteristics of the tilting-disc valve include:

- Superior durability compared to bioprosthetic valves.

- Creation of two unequal orifices (major and minor) during the open phase.

- A distinct “clicking” sound that can sometimes be heard upon closure.

- A requirement for consistent, lifelong anticoagulation therapy.

Clinical Context: Valvular Heart Disease

The primary medical indication for implanting a tilting-disc valve is severe valvular heart disease, specifically pathology affecting the aortic or mitral valves. One of the most common conditions requiring this intervention is aortic stenosis. In this disease, the natural aortic valve becomes calcified and stiff, narrowing the opening and forcing the left ventricle to work harder to pump blood into the aorta. Over time, this causes ventricular hypertrophy (thickening of the heart muscle) and can lead to heart failure. By replacing the diseased valve with a tilting-disc prosthesis, surgeons restore the normal outflow tract, relieving the pressure overload on the heart.

Another major indication is valvular regurgitation, where the leaflets of the native valve fail to close completely, causing blood to leak backward. In mitral regurgitation, for example, blood flows back into the left atrium during contraction, reducing cardiac output and causing fluid congestion in the lungs. The mechanical valve provides a competent seal, ensuring unidirectional flow. However, the introduction of a mechanical surface into the bloodstream presents a risk of thromboembolism. Without proper management, clots can form on the valve struts or hinge, potentially breaking loose and causing a stroke.

To mitigate this risk, patients with tilting-disc valves must remain on permanent anticoagulation therapy, typically using a Vitamin K antagonist like Warfarin. Physicians monitor the patient’s International Normalized Ratio (INR) regularly to ensure the blood is thin enough to prevent clots but not so thin as to cause dangerous bleeding. While this requirement adds a layer of complexity to the patient’s lifestyle, the trade-off is a robust, life-saving device that effectively restores normal cardiac physiology.

Conclusion

The tilting-disc valve remains a cornerstone in the history and current practice of cardiovascular surgery. Its sophisticated engineering balances the need for structural longevity with the physiological requirement for efficient blood flow. While newer bioprosthetic options and transcatheter technologies continue to evolve, the mechanical tilting-disc valve offers an unmatched lifespan for younger patients facing severe valvular disease. Understanding the anatomy of the housing, cuff, and occluder helps clarify both the benefits of the device and the necessity for rigorous postoperative care, ensuring that patients can lead active, healthy lives after their procedure.