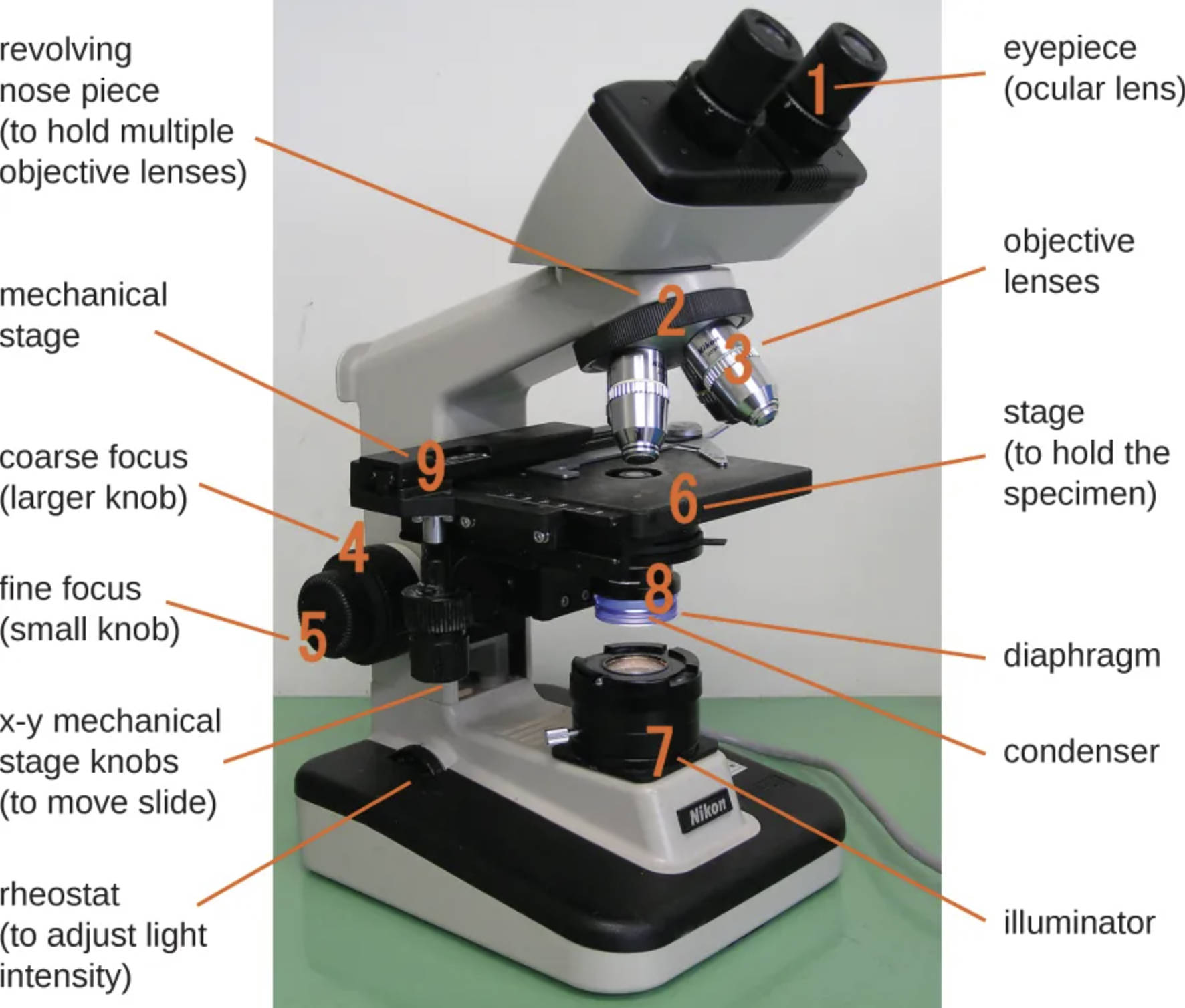

The brightfield microscope is the quintessential instrument in medical diagnostics and biological research, enabling the visualization of cellular structures that are otherwise invisible to the naked eye. This guide provides a detailed breakdown of the microscope’s components as depicted in the image, explaining the optical and mechanical systems that work together to produce high-resolution images for clinical analysis.

Detailed Component Analysis

Eyepiece (ocular lens)

The eyepiece contains the lenses that the observer looks through to view the specimen. It typically provides a tenfold magnification (10x) and works in conjunction with the objective lenses to calculate the final magnification of the image.

Revolving nose piece

This rotating mechanism holds the various objective lenses in place above the stage. It allows the user to switch easily between different magnification levels by physically clicking a new lens into the optical path.

Objective lenses

These are the primary optical lenses responsible for capturing light from the specimen and creating the initial magnified image. They come in varying powers, such as scanning (4x), low power (10x), high dry (40x), and oil immersion (100x), to suit different diagnostic needs.

Coarse focus (larger knob)

The coarse focus knob is used to move the stage vertically in significant increments. It is primarily utilized with low-power objective lenses to bring the specimen into the general field of view before fine-tuning the image.

Fine focus (small knob)

This smaller knob allows for minute, precise vertical adjustments of the stage. It is essential for sharpening the image resolution, particularly when using high-power objectives where the depth of field is extremely shallow.

Stage

The stage is the flat, rigid platform where the microscope slide is placed for observation. It contains a central aperture that allows light from the illuminator to pass through the specimen and into the objective lens.

Illuminator

Located at the base of the microscope, the illuminator serves as the steady light source, typically using a halogen bulb or LED. It projects light upward through the condenser and specimen to enable brightfield visualization.

Condenser

Situated beneath the stage, the condenser is a lens system that collects and concentrates light from the illuminator into a cone of light that illuminates the specimen. Proper adjustment of the condenser is crucial for achieving optimal resolution and contrast.

Mechanical stage

This apparatus is mounted on top of the stage platform and secures the slide in place with a spring-loaded clip. It allows for controlled movement of the slide, ensuring the user can scan the entire specimen systematically without touching it.

X-y mechanical stage knobs

These coaxial controls allow the user to move the mechanical stage and the slide along the X (horizontal) and Y (vertical) axes. This precise movement is vital for centering the area of interest within the field of view.

Rheostat

The rheostat acts as a dimmer switch that controls the electrical current flowing to the illuminator. By adjusting this dial, the user can increase or decrease the light intensity to prevent eye strain and optimize the image based on the specimen’s density.

Diaphragm

Often integrated with the condenser, the iris diaphragm regulates the diameter of the light beam passing through to the specimen. Adjusting the diaphragm helps balance resolution and contrast, which is particularly important for viewing transparent or unstained samples.

The Role of Microscopy in Medical Science

The brightfield microscope is the standard workhorse of clinical laboratories, utilized extensively in pathology, histology, and microbiology. It operates on the principle of transmitting light through a translucent specimen. The specimen appears dark against a bright background, hence the name “brightfield.” This contrast allows medical professionals to identify cell morphology, bacteria, and tissue architecture. The instrument shown is a compound microscope, meaning it employs two separate lens systems (the objective and the ocular) to achieve higher magnification than a simple magnifying glass could provide.

The efficacy of this instrument relies heavily on the concept of total magnification, which is calculated by multiplying the magnification power of the objective lens by that of the eyepiece. For instance, using a 40x objective with a 10x eyepiece results in a 400x total magnification. However, magnification alone is not sufficient for medical diagnosis; resolution—the ability to distinguish two close points as separate entities—is equally critical. The condenser and diaphragm play pivotal roles in manipulating the light path to maximize this resolution, allowing for the clear distinction of nuclear details or bacterial shapes.

In a clinical setting, proper manipulation of these mechanical and optical components is essential for accurate diagnostics. For example, when examining a blood smear to identify leukemia or anemia, the user must employ the oil immersion objective (100x) and adjust the fine focus to see the specific granulation inside white blood cells. Similarly, in histology, pathologists use lower magnifications to scan tissue architecture before zooming in to check for cellular abnormalities indicative of cancer.

Key applications of this optical system include:

- Hematology: Examining blood cells for counts and morphological abnormalities.

- Microbiology: Identifying bacteria, fungi, and parasites through Gram staining and wet mounts.

- Histopathology: analyzing thin tissue sections to diagnose diseases such as cancer.

- Cytology: Screening loose cells, such as in Pap smears, for pre-cancerous changes.

Conclusion

Understanding the anatomy of a microscope is fundamental for any medical professional or laboratory technician. Each component, from the rheostat controlling light intensity to the precision of the x-y mechanical stage knobs, plays a specific role in generating a clear, interpretable image. Mastery of these controls ensures that the optical physics of the instrument are fully leveraged, resulting in accurate data that supports patient diagnosis and treatment planning.