The human vascular system relies on the robust and elastic architecture of arteries to transport oxygenated blood from the heart to peripheral tissues efficiently. This article provides an in-depth analysis of the structure of an artery wall, exploring the distinct functions of the tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica externa in maintaining hemodynamic stability and vascular health. By understanding the microscopic anatomy of these vessels, we gain insight into how the body regulates blood pressure and sustains vital organ function.

Anatomical Components of the Artery Wall

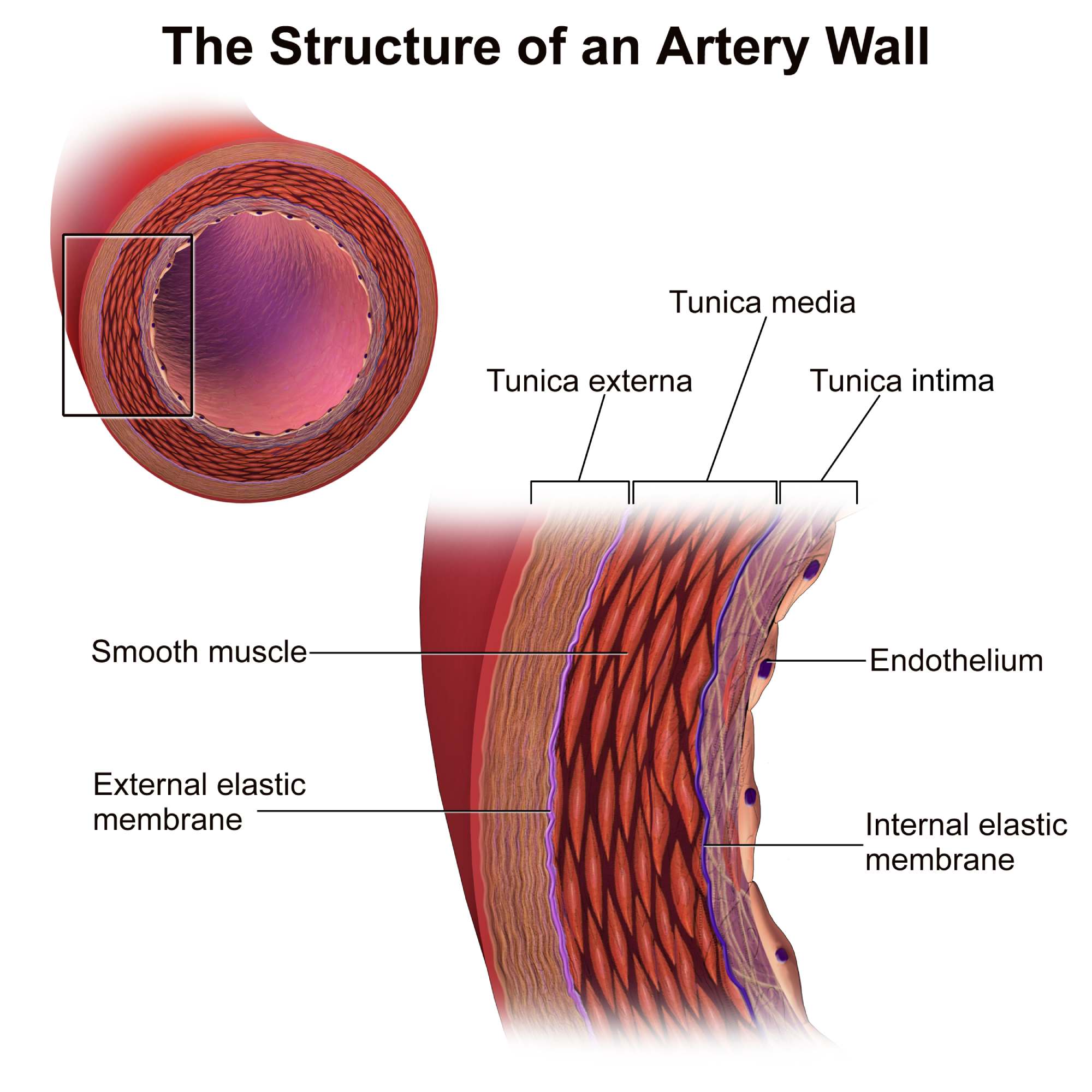

Tunica media:

This is typically the thickest layer of the arterial wall, situated between the inner and outer tunics. It is composed primarily of concentrically arranged smooth muscle cells and varying amounts of elastic fibers, which allow the vessel to regulate its diameter and withstand blood pressure.

Tunica externa:

Also known as the tunica adventitia, this is the outermost layer of the blood vessel wall. It consists mainly of collagen fibers that reinforce the vessel, prevent it from over-expanding, and anchor the artery to surrounding structures and tissues.

Tunica intima:

The tunica intima is the innermost layer of the artery, directly in contact with the flowing blood. It is a thin structure comprised of the endothelium and a subendothelial layer of delicate connective tissue, playing a critical role in minimizing friction and preventing blood clot formation.

Smooth muscle:

Located predominantly within the tunica media, these muscle fibers are arranged in a circular pattern around the lumen of the artery. Their contraction and relaxation are controlled by the autonomic nervous system and local chemical signals, driving vasoconstriction and vasodilation to manage blood flow distribution.

Endothelium:

The endothelium is a specialized single layer of simple squamous epithelial cells that lines the interior surface of the blood vessel. Beyond acting as a physical barrier, these cells are metabolically active, releasing substances like nitric oxide to control vascular tone, immune response, and platelet adhesion.

External elastic membrane:

This is a distinct band of elastic fibers found at the boundary between the tunica media and the tunica externa. It provides additional structural support and flexibility, allowing the artery to stretch during the high-pressure systolic phase of the cardiac cycle and recoil during diastole.

Internal elastic membrane:

Also called the internal elastic lamina, this fenestrated layer of elastic tissue separates the tunica intima from the tunica media. Its porous structure facilitates the diffusion of nutrients from the blood in the lumen to the deeper layers of the vessel wall while contributing to arterial elasticity.

The Physiology of Arterial Layers

The architecture of an artery is a perfect example of form following function. Unlike veins, which operate under low pressure and rely on valves to prevent backflow, arteries must handle the high-pressure output of the left ventricle. To accomplish this, the arterial wall is organized into three concentric coats, or tunicas, each contributing to the vessel’s overall vascular compliance. The structural integrity provided by these layers prevents the vessel from rupturing under pressure, while their elasticity ensures a continuous flow of blood even when the heart is in its resting phase (diastole).

The composition of the arterial wall changes depending on the vessel’s distance from the heart. Large arteries near the heart, such as the aorta, are rich in elastic fibers to absorb the immediate shock of the heartbeat. As arteries branch into smaller muscular arteries, the proportion of smooth muscle increases relative to elastic tissue. This muscular component is vital for the regulation of systemic vascular resistance. By constricting or dilating, these vessels can direct blood flow to active tissues—such as muscles during exercise—or conserve heat by reducing blood flow to the skin in cold environments.

The innermost aspect of the wall, the endothelium, is much more than a passive lining; it is a dynamic interface between the blood and the vessel wall. A healthy endothelium maintains an anti-thrombotic surface, preventing clots that could lead to strokes or heart attacks. However, chronic stress from factors like high blood pressure or high cholesterol can damage this layer, leading to atherosclerosis. This pathological process involves the hardening of the arteries and plaque buildup within the tunica intima, significantly impairing the vessel’s ability to function.

Key functions of the arterial wall structure include:

- Pressure Management: The elastic components dampen the pulsatile force of the heart, converting it into a smoother flow.

- Flow Regulation: Smooth muscle contraction alters the lumen size to control blood pressure and distribution.

- Structural Support: Collagen in the outer layers prevents aneurysm formation and rupture.

- Diffusion: Fenestrations (pores) in the elastic membranes allow nutrients to reach cells deep within the vessel wall.

Conclusion

The complex histology of the artery wall underscores the sophistication of the cardiovascular system. From the protective outer collagen of the tunica externa to the delicate, signaling capabilities of the endothelium, every layer works in concert to ensure hemodynamics are maintained within a physiological range. A deep understanding of these structures is essential for medical professionals, as many cardiovascular diseases originate from dysfunctions within these specific layers.