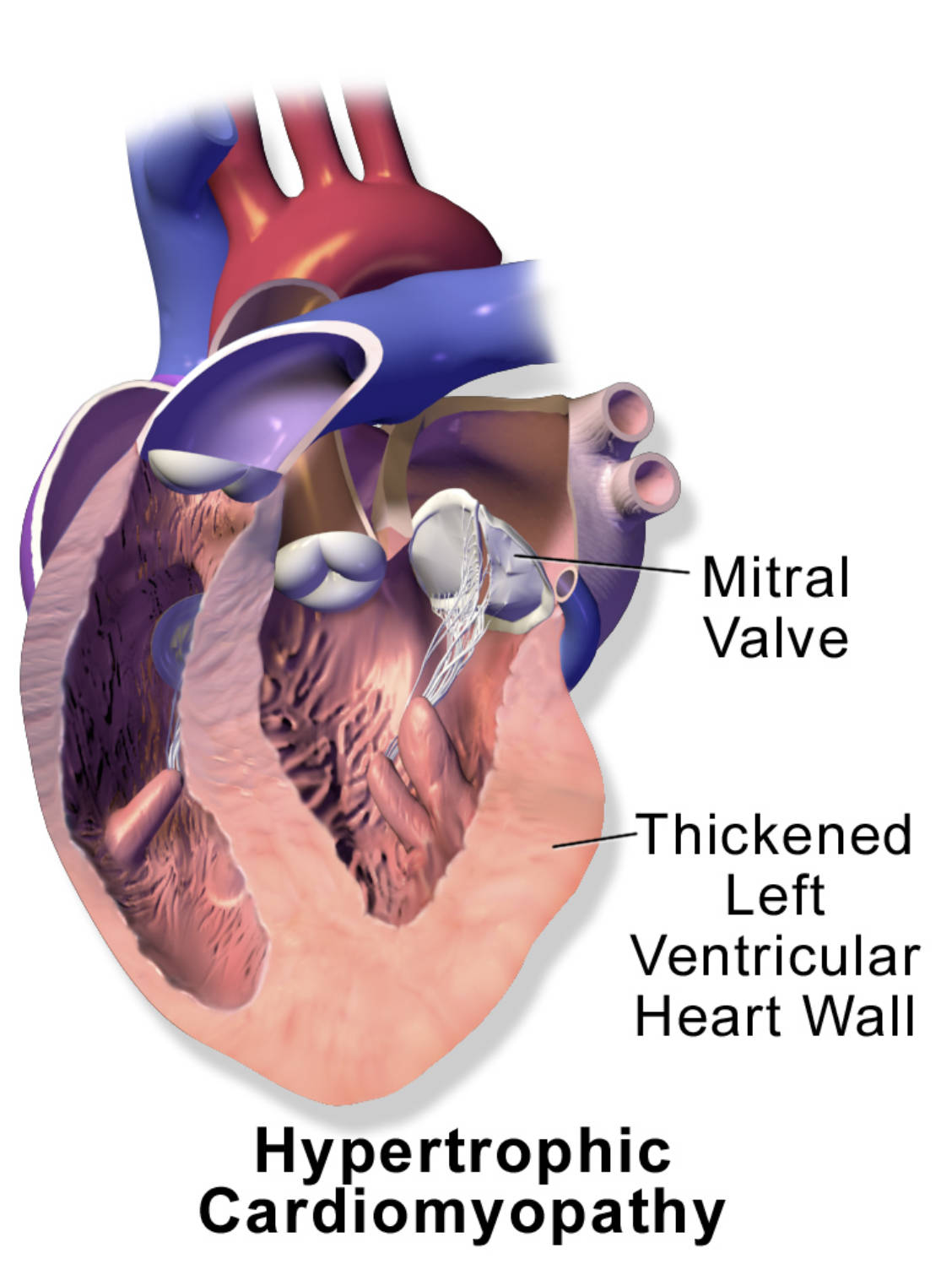

This article provides a detailed exploration of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), a genetic heart condition characterized by abnormal thickening of the heart muscle, as vividly depicted in the provided diagram. We will examine the specific structural changes that occur in the left ventricle, discuss how this thickening impedes normal cardiac function, and highlight the potential consequences for blood flow and overall cardiovascular health. This comprehensive overview aims to enhance understanding for medical professionals and the general public alike regarding this significant cardiac pathology.

Mitral Valve: This valve is situated between the left atrium and the left ventricle. In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the thickened septum can sometimes interfere with the proper function of this valve, leading to mitral regurgitation.

Thickened Left Ventricular Heart Wall: This label points to the hallmark anatomical feature of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an abnormal and often asymmetric thickening of the muscular walls of the left ventricle. This thickening, particularly of the interventricular septum, can obstruct the outflow of blood from the heart.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetic disorder of the heart muscle, affecting approximately 1 in 500 individuals globally. It is primarily characterized by the abnormal thickening of the heart muscle, particularly the left ventricle, without any obvious cause such as prolonged high blood pressure or aortic valve stenosis. The diagram provides a clear illustration of this key pathological feature, highlighting the Thickened Left Ventricular Heart Wall. This excessive muscle growth significantly impacts the heart’s ability to function efficiently, leading to a range of physiological consequences that can severely compromise cardiovascular health.

The thickening of the heart muscle, especially the interventricular septum (the wall separating the left and right ventricles), can create an obstruction to blood flow out of the left ventricle into the aorta. This phenomenon is known as left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction. Even in cases without significant obstruction, the stiffened and thickened ventricle struggles to relax and fill properly during diastole, leading to diastolic dysfunction. HCM is also a leading cause of sudden cardiac death in young athletes and adults.

Understanding the unique structural and functional abnormalities associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is critical for accurate diagnosis, effective management, and personalized risk stratification. The genetic basis of the condition further emphasizes the importance of family screening.

- Muscle Hypertrophy: The heart muscle, particularly the left ventricle, grows abnormally thick.

- Outflow Obstruction: Thickening of the septum can block blood flow from the left ventricle to the aorta.

- Diastolic Dysfunction: The stiffened ventricle has difficulty relaxing and filling with blood.

These factors contribute to the complex clinical presentation and potential severity of HCM.

The Pathophysiology of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is predominantly an autosomal dominant genetic disorder, meaning that a single copy of an altered gene is sufficient to cause the condition. Over 1,500 mutations in at least 15 sarcomere protein genes, which are responsible for heart muscle contraction, have been identified as causes of HCM. These mutations lead to disorganized myocardial fibers (myocyte disarray) and interstitial fibrosis (scarring), which contribute to the abnormal thickening and stiffness of the heart muscle. The Thickened Left Ventricular Heart Wall is a direct consequence of this genetic predisposition and cellular pathology.

The primary physiological consequences of this hypertrophy include impaired diastolic function and potential left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction. Diastolic dysfunction occurs because the thickened, stiffened ventricle cannot relax effectively to allow for proper filling with blood during diastole. This leads to elevated filling pressures in the left ventricle and subsequently in the left atrium and pulmonary veins, causing symptoms of heart failure. LVOT obstruction occurs in approximately two-thirds of HCM patients. It happens when the thickened interventricular septum bulges into the outflow tract, and in some cases, the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve is pulled towards the septum during systole (systolic anterior motion, or SAM) due to the Venturi effect, further impeding blood flow out of the left ventricle into the aorta. This obstruction increases the workload on the left ventricle and reduces cardiac output.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis of HCM

The clinical presentation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is highly variable, ranging from asymptomatic individuals to those with severe symptoms and even sudden cardiac death. Symptoms often manifest during adolescence or early adulthood, but can appear at any age. Common symptoms include shortness of breath, especially during exertion, due to diastolic dysfunction and elevated pulmonary pressures. Chest pain (angina) can occur due to increased myocardial oxygen demand from the thickened muscle and impaired coronary blood flow. Palpitations and lightheadedness or syncope (fainting) may result from arrhythmias, particularly ventricular arrhythmias, which are a major risk factor for sudden cardiac death. In some cases, the first manifestation of HCM is sudden cardiac death, making early diagnosis and risk stratification critical.

Diagnosis of HCM typically involves a thorough medical history, a detailed family history for sudden cardiac death or HCM, and a physical examination where a characteristic systolic murmur may be heard. An electrocardiogram (ECG) often shows abnormalities such as left ventricular hypertrophy, ST-T wave changes, and Q waves, but these are not specific. The cornerstone of diagnosis is an echocardiogram, which provides detailed images of the heart’s structure and function. It can precisely measure wall thickness, identify LVOT obstruction, assess diastolic function, and detect mitral regurgitation. Cardiac MRI offers even more detailed anatomical and tissue characterization, including detection of myocardial fibrosis. Genetic testing is often recommended for affected individuals and their family members to identify specific mutations.

Management and Prognosis for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

The management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy aims to alleviate symptoms, prevent complications, and reduce the risk of sudden cardiac death. Treatment strategies are highly individualized and typically involve pharmacological therapy, lifestyle modifications, and, in some cases, invasive procedures. Beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers (non-dihydropyridine type, like verapamil or diltiazem) are the mainstays of medical therapy. They work by reducing heart rate, improving diastolic filling, and decreasing myocardial contractility, thereby reducing LVOT obstruction and relieving symptoms. Diuretics may be used cautiously to manage fluid retention, but excessive diuresis can worsen LVOT obstruction.

For patients at high risk of sudden cardiac death, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is recommended. In patients with severe, drug-refractory LVOT obstruction, invasive procedures may be considered. These include septal myectomy, a surgical procedure to remove a portion of the thickened interventricular septum, or alcohol septal ablation, a catheter-based procedure that induces a controlled infarction of the septal muscle. Lifestyle modifications, such as avoiding strenuous exercise and dehydration, are also important. Genetic counseling is crucial for patients and their families. With appropriate management, many individuals with HCM can lead full and active lives, though lifelong follow-up with a cardiologist specializing in HCM is essential.