Explore the critical electrocardiogram (ECG) findings associated with acquired Long QT Syndrome, a potentially life-threatening cardiac condition. This article provides a detailed explanation of how a prolonged QT interval can manifest on an ECG, its clinical implications, and the importance of prompt recognition and management.

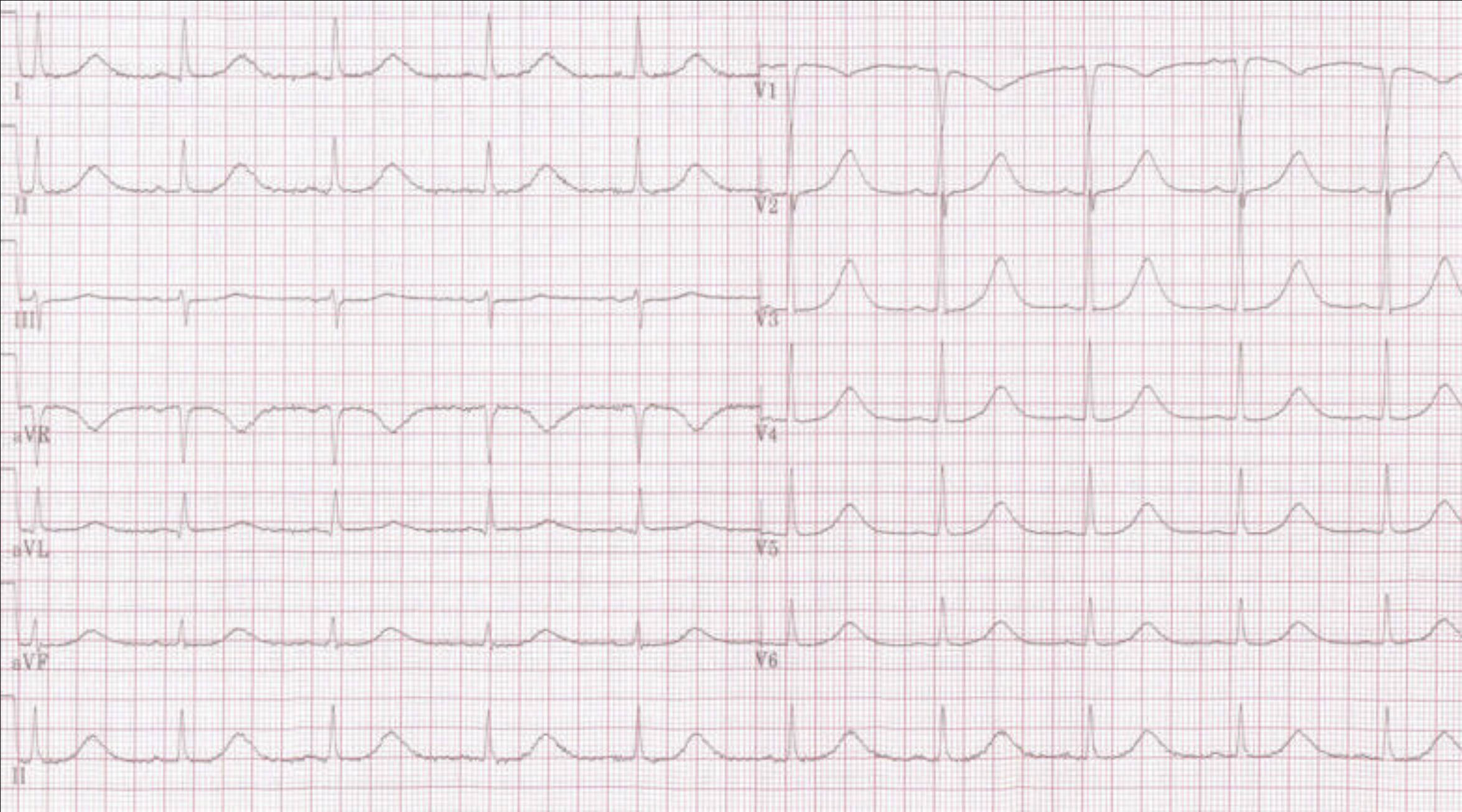

I, II, III, aVR, aVL, aVF, V1-V6: These labels refer to the standard 12 leads of an electrocardiogram (ECG), each offering a distinct electrical perspective of the heart’s activity. The grid pattern on the ECG paper facilitates precise measurement of intervals and amplitudes, which are crucial for accurate interpretation of cardiac electrical events.

De-Acquired longQT (cropped): This indicates that the presented electrocardiogram (ECG) tracing exhibits features consistent with acquired Long QT Syndrome, an abnormality characterized by a prolonged QT interval. The term “de-acquired” might imply a state where the condition is being managed or its cause has been removed, though the primary focus here is on the ECG manifestation of long QT.

An electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) is a cornerstone diagnostic tool in cardiology, providing a non-invasive visual representation of the heart’s electrical activity. By recording the tiny electrical impulses that govern each heartbeat, the ECG offers critical insights into the heart’s rhythm, conduction system, and the presence of various cardiac pathologies. Among the many conditions an ECG can help identify, acquired Long QT Syndrome is of particular importance due to its potential for life-threatening arrhythmias. Understanding the characteristic ECG findings associated with this condition is paramount for timely diagnosis and effective management.

Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) is a disorder of the heart’s electrical activity characterized by a prolonged QT interval on the ECG. The QT interval represents the time it takes for the ventricles to depolarize (contract) and repolarize (relax). A prolonged QT interval indicates a delay in ventricular repolarization, which can make the heart more susceptible to a dangerous type of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia called Torsades de Pointes (TdP). TdP can degenerate into ventricular fibrillation, leading to sudden cardiac death. While there are inherited forms of LQTS, acquired LQTS is more common and often precipitated by certain medications or electrolyte imbalances.

The ECG tracing provided exemplifies the appearance of a prolonged QT interval, a hallmark of acquired Long QT Syndrome. Recognizing this elongation is critical for clinicians, as it can be an early indicator of increased risk for serious cardiac events. The careful measurement and interpretation of the QT interval, often corrected for heart rate (QTc), are essential components of ECG analysis in both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals.

- Long QT Syndrome is characterized by a prolonged QT interval on ECG.

- It can lead to a dangerous arrhythmia called Torsades de Pointes.

- Acquired LQTS is often caused by medications or electrolyte imbalances.

- The QTc interval is crucial for diagnosis and risk assessment.

On an ECG, the QT interval is measured from the beginning of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave. While a precise definition can vary, a QTc interval (corrected QT interval for heart rate using formulas like Bazett’s or Fridericia’s) typically exceeding 440-450 ms in males and 460-470 ms in females is considered prolonged. The morphology of the T wave can also provide clues, with broad, notched, or bifid T waves sometimes accompanying a prolonged QT. In the provided image, one can observe the extended duration from the QRS complex to the end of the T wave, consistent with such a prolongation.

A wide array of factors can lead to acquired LQTS, with medications being the most frequent culprits. Many antiarrhythmic drugs, antidepressants, antihistamines, antibiotics (e.g., macrolides, fluoroquinolones), and antifungals can block cardiac potassium channels, thereby delaying repolarization and prolonging the QT interval. Electrolyte disturbances, particularly hypokalemia (low potassium), hypomagnesemia (low magnesium), and hypocalcemia (low calcium), are also significant causes, as these ions play crucial roles in cardiac electrical stability. Other contributors include severe bradycardia, myocardial ischemia, and central nervous system disorders.

The clinical implications of acquired LQTS are substantial. Patients may be asymptomatic, or they may present with symptoms such as palpitations, lightheadedness, syncope (fainting), or even sudden cardiac arrest. The risk of developing Torsades de Pointes and subsequent sudden cardiac death increases with the degree of QT prolongation. Management primarily involves identifying and discontinuing the offending medication or correcting the underlying electrolyte imbalance. In some cases, temporary cardiac pacing or magnesium infusion may be necessary to stabilize the rhythm. For individuals at very high risk, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) may be considered.

In conclusion, acquired Long QT Syndrome is a critical cardiac condition identifiable through a prolonged QT interval on the electrocardiogram. Its diverse etiologies, predominantly drug-induced or electrolyte-mediated, underscore the importance of careful medication review and electrolyte monitoring in clinical practice. Prompt recognition of a prolonged QTc on an ECG is paramount, as it alerts clinicians to the increased risk of potentially fatal ventricular arrhythmias like Torsades de Pointes. Through vigilant screening and appropriate therapeutic interventions, the severe consequences associated with acquired Long QT Syndrome can often be prevented, significantly improving patient safety and outcomes in cardiology.