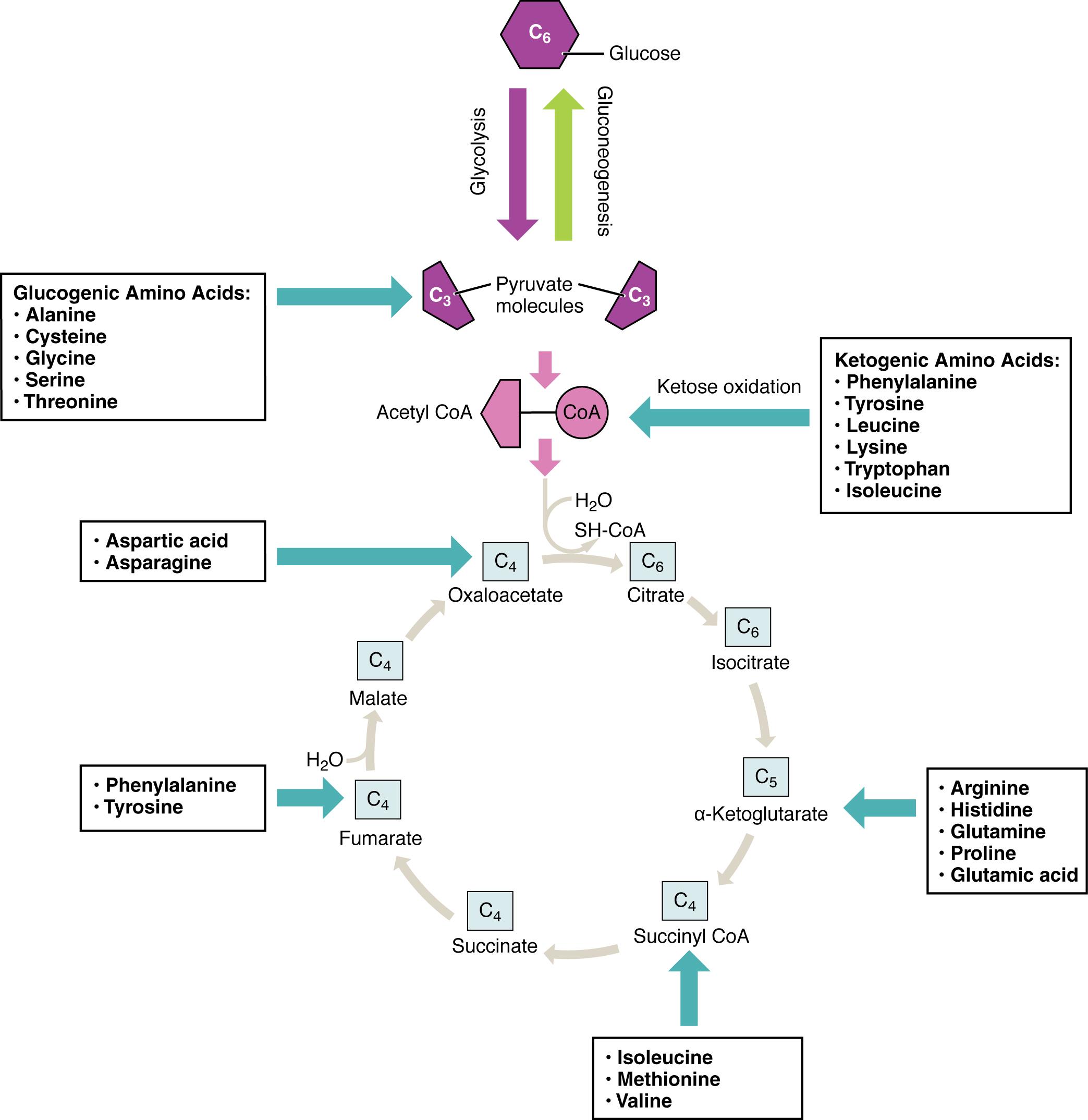

This article explores how amino acids contribute to energy production, detailing their breakdown into precursors for glycolysis and the Krebs cycle. Understand the classifications of glucogenic and ketogenic amino acids, and their diverse entry points into metabolic pathways.

Glucose C6: Glucose is a six-carbon sugar, serving as a primary energy source for cells. It is the starting point for glycolysis, a metabolic pathway that breaks down glucose to produce ATP.

Glycolysis: Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose into pyruvate, occurring in the cytoplasm of cells. This process generates a small amount of ATP and NADH, preparing glucose for further oxidation in the mitochondria.

Gluconeogenesis: Gluconeogenesis is the metabolic pathway that synthesizes glucose from non-carbohydrate precursors, such as amino acids, lactate, and glycerol. This process is crucial for maintaining blood glucose levels, especially during fasting or prolonged exercise.

Pyruvate molecules C3: Pyruvate is a three-carbon alpha-keto acid that is the end product of glycolysis. It serves as a crucial branching point, leading to either aerobic respiration (via acetyl CoA) or fermentation, depending on oxygen availability.

Acetyl CoA: Acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl CoA) is a central molecule in metabolism, formed from the breakdown of carbohydrates, fats, and amino acids. It is the primary substrate that enters the Krebs cycle, linking glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation to cellular respiration.

Ketose oxidation: Ketose oxidation refers to the metabolic processes that break down ketone bodies for energy. Ketogenic amino acids can be converted into ketone bodies or their precursors, providing an alternative fuel source.

Glucogenic Amino Acids: Alanine, Cysteine, Glycine, Serine, Threonine: These amino acids can be converted into glucose through gluconeogenesis. Their carbon skeletons can be transformed into pyruvate or intermediates of the Krebs cycle, which then serve as precursors for glucose synthesis.

Ketogenic Amino Acids: Phenylalanine, Tyrosine, Leucine, Lysine, Tryptophan, Isoleucine: These amino acids are broken down into acetyl CoA or acetoacetate, which can be used to synthesize fatty acids or ketone bodies. They cannot be directly converted into glucose.

Aspartic acid, Asparagine C4: These amino acids are glucogenic and can be converted into oxaloacetate, a four-carbon intermediate of the Krebs cycle. Their catabolism directly contributes to the pool of intermediates available for glucose synthesis.

Oxaloacetate C4: Oxaloacetate is a four-carbon dicarboxylic acid that is a key intermediate in the Krebs cycle. It also serves as a crucial precursor for gluconeogenesis, linking carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism.

Citrate C6: Citrate is a six-carbon tricarboxylic acid formed by the condensation of acetyl CoA and oxaloacetate, marking the beginning of the Krebs cycle. It is also an important regulatory molecule, influencing other metabolic pathways.

Isocitrate C6: Isocitrate is a six-carbon isomer of citrate, further processed in the Krebs cycle. It undergoes oxidative decarboxylation, releasing carbon dioxide and generating NADH.

α-Ketoglutarate C5: Alpha-ketoglutarate is a five-carbon alpha-keto acid that is a central intermediate in the Krebs cycle. It is also a precursor for the synthesis of several amino acids, including glutamate.

Arginine, Histidine, Glutamine, Glutamate, Proline, Glutamic acid: These are glucogenic amino acids that can be converted into alpha-ketoglutarate, a five-carbon intermediate of the Krebs cycle. Their breakdown directly replenishes intermediates for both energy production and glucose synthesis.

Succinyl CoA C4: Succinyl coenzyme A (succinyl CoA) is a four-carbon intermediate in the Krebs cycle, also playing a role in heme synthesis. It is formed from alpha-ketoglutarate and is further metabolized to succinate.

Isoleucine, Methionine, Valine C4: These are glucogenic amino acids whose carbon skeletons can be converted into succinyl CoA, a four-carbon intermediate of the Krebs cycle. This pathway allows them to contribute to both energy production and glucose synthesis.

Succinate C4: Succinate is a four-carbon dicarboxylic acid that is an intermediate in the Krebs cycle. It is oxidized to fumarate, a reaction that generates FADH2.

Fumarate C4: Fumarate is a four-carbon dicarboxylic acid that is an intermediate in the Krebs cycle. It can also be formed from the breakdown of certain amino acids, linking their metabolism to the energy production pathway.

Malate C4: Malate is a four-carbon dicarboxylic acid that is an intermediate in the Krebs cycle. It is oxidized to oxaloacetate, completing the cycle and generating NADH.

Phenylalanine, Tyrosine: These amino acids are unique because they are both glucogenic and ketogenic. Their breakdown products can enter the Krebs cycle at different points (fumarate and acetyl CoA), allowing them to contribute to both glucose and ketone body synthesis.

Amino acids are the fundamental building blocks of proteins, essential for virtually all cellular functions. Beyond their structural roles, they also serve as a crucial source of energy, particularly when carbohydrate and fat reserves are low, such as during prolonged fasting or intense exercise. The body possesses intricate metabolic pathways to break down amino acids, converting their carbon skeletons into intermediates that can enter the central energy-producing cycles: glycolysis and the Krebs cycle. This remarkable adaptability ensures a continuous supply of ATP, the cell’s primary energy currency.

The metabolic fate of an amino acid’s carbon skeleton dictates whether it is classified as glucogenic, ketogenic, or both. Glucogenic amino acids are those whose catabolism yields pyruvate or intermediates of the Krebs cycle, which can then be used to synthesize glucose through gluconeogenesis. This process is vital for maintaining blood glucose levels, especially for tissues like the brain that primarily rely on glucose for fuel. Conversely, ketogenic amino acids are broken down into acetyl CoA or acetoacetate, which can be converted into ketone bodies or fatty acids.

This diagram illustrates the diverse entry points of various amino acids into these key metabolic pathways. It highlights how a single glucose molecule can be broken down into pyruvate via glycolysis, and how amino acids can feed into this pathway or directly into the Krebs cycle. The cyclical nature of the Krebs cycle, also known as the citric acid cycle, is central to aerobic respiration, systematically oxidizing acetyl CoA and generating electron carriers that drive ATP synthesis. Understanding these connections is fundamental to comprehending the holistic view of cellular energy metabolism.

- Amino acids can be used for energy when carbohydrate and fat stores are low.

- Glucogenic amino acids can be converted into glucose.

- Ketogenic amino acids can be converted into ketone bodies or fatty acids.

- The Krebs cycle is a central hub for amino acid catabolism.

The breakdown of amino acids for energy is a complex process initiated by the removal of their amino group, typically through transamination or deamination. The remaining carbon skeleton is then channeled into specific metabolic routes. For instance, glucogenic amino acids like alanine, cysteine, glycine, serine, and threonine are converted into pyruvate. Pyruvate can then be further metabolized to acetyl CoA to enter the Krebs cycle, or it can be used for gluconeogenesis to synthesize new glucose molecules. This flexibility underscores the body’s capacity to adapt its fuel sources based on physiological needs.

Other glucogenic amino acids, such as aspartic acid and asparagine, directly feed into the Krebs cycle by being converted to oxaloacetate. Arginine, histidine, glutamine, glutamate, and proline enter the cycle via alpha-ketoglutarate, another key intermediate. Even succinyl CoA, an intermediate in the Krebs cycle, can be formed from the breakdown of isoleucine, methionine, and valine. This wide array of entry points demonstrates how the body efficiently integrates amino acid metabolism into its primary energy-generating pathways.

Interestingly, some amino acids, like phenylalanine and tyrosine, possess both glucogenic and ketogenic properties. Their catabolism yields products that can either contribute to glucose synthesis (via fumarate) or ketone body/fatty acid synthesis (via acetyl CoA). This dual nature provides even greater metabolic flexibility, allowing these amino acids to support various energy demands. Conditions like Phenylketonuria (PKU), a genetic disorder affecting the metabolism of phenylalanine, highlight the critical importance of these pathways. In PKU, the inability to break down phenylalanine leads to its toxic accumulation, causing severe neurological damage if not managed with a specialized diet from birth.

In conclusion, the intricate pathways governing energy from amino acids are vital for maintaining metabolic homeostasis, particularly during periods of metabolic stress. The classification of amino acids as glucogenic, ketogenic, or both reflects their diverse entry points into glycolysis and the Krebs cycle, showcasing the body’s remarkable adaptability in fuel utilization. Understanding these metabolic connections is not only fundamental to biochemistry but also crucial for comprehending and managing various metabolic disorders, reinforcing the profound impact of amino acid metabolism on overall human health.