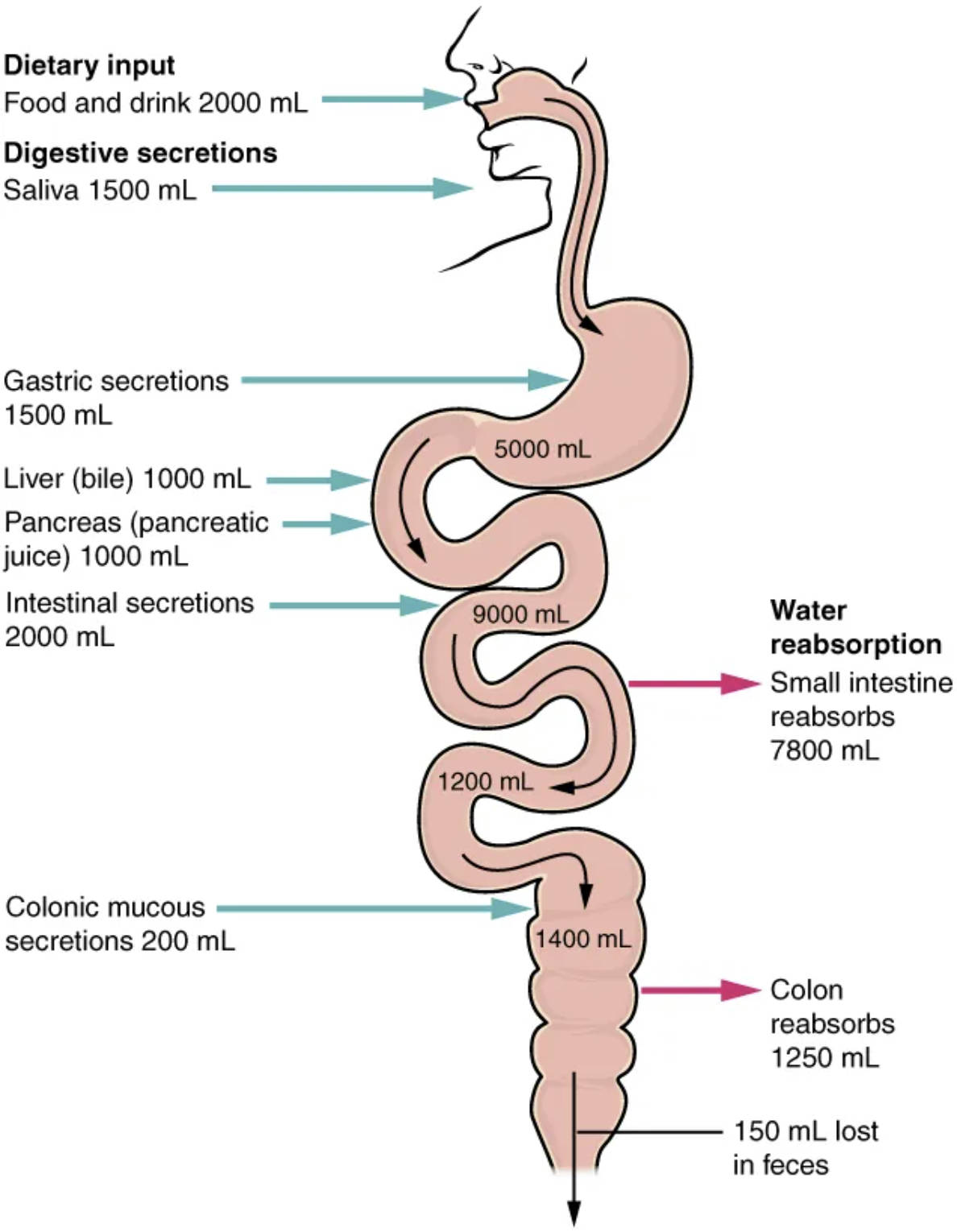

The human digestive system is a marvel of efficiency, not only in breaking down food but also in managing the substantial volume of fluids involved in this process. This illustrative diagram highlights the complex interplay between digestive secretions and subsequent water reabsorption, revealing how the body maintains a precise fluid balance while extracting nutrients. Understanding this dynamic fluid exchange is crucial for appreciating overall digestive health and the body’s remarkable ability to recycle vast quantities of water daily.

Dietary input: This represents the total volume of food and drink consumed by an individual daily, estimated here as 2000 mL. This intake is the initial source of fluid and nutrients entering the digestive tract.

Saliva: Produced by salivary glands in the mouth, approximately 1500 mL of saliva is secreted daily. Saliva aids in moistening food, initiating carbohydrate digestion, and lubricating the food bolus for swallowing.

Gastric secretions: The stomach produces around 1500 mL of gastric juice daily, consisting of hydrochloric acid, enzymes, and mucus. These secretions are vital for protein digestion and creating an acidic environment.

Liver (bile): The liver continuously produces bile, with an estimated 1000 mL secreted daily into the digestive tract. Bile is essential for the emulsification and absorption of dietary fats in the small intestine.

Pancreas (pancreatic juice): The pancreas secretes approximately 1000 mL of pancreatic juice daily, rich in digestive enzymes and bicarbonate. This juice neutralizes stomach acid and breaks down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats in the small intestine.

Intestinal secretions: The small intestine itself produces about 2000 mL of various secretions daily, including water, mucus, and enzymes from the intestinal wall. These secretions facilitate digestion and nutrient absorption.

Water reabsorption (Small intestine reabsorbs 7800 mL): The small intestine is the primary site for water reabsorption, efficiently recovering a massive 7800 mL of fluid. This high volume accounts for the majority of the fluid absorbed back into the bloodstream from the digestive tract.

Colonic mucous secretions: The colon produces approximately 200 mL of mucous secretions daily. This mucus lubricates the passage of feces and protects the colonic lining.

Water reabsorption (Colon reabsorbs 1250 mL): The large intestine, or colon, plays a crucial role in final water recovery, reabsorbing an additional 1250 mL of fluid. This process helps to solidify fecal matter.

150 mL lost in feces: Out of the vast amount of fluid processed by the digestive system, only a small volume, typically around 150 mL, is ultimately expelled in feces. This demonstrates the high efficiency of water reabsorption.

The human digestive system is not merely a conduit for food; it is a sophisticated biochemical factory and a highly efficient fluid management system. Each day, a remarkable volume of fluid, far exceeding our dietary intake, cycles through the digestive tract. This fluid comprises both ingested food and drink, along with copious digestive secretions from various glands and organs. The diagram strikingly illustrates this massive fluid turnover, highlighting the critical balance between secretion and reabsorption that is essential for nutrient harvesting and maintaining bodily hydration.

The total daily fluid entering the digestive lumen is staggering. Considering the dietary input of approximately 2000 mL, combined with an average of 1500 mL of saliva, 1500 mL of gastric secretions, 1000 mL of bile from the liver, 1000 mL of pancreatic juice, and 2000 mL of intestinal secretions, the cumulative volume flowing through the system reaches roughly 9000 mL. This substantial volume is indispensable for chemical digestion, dissolving nutrients, lubricating the passage of food, and facilitating enzymatic reactions. Without this constant flow, the digestive process would grind to a halt.

While a significant amount of fluid is secreted into the digestive tract, the body is exceptionally adept at reclaiming this fluid. The vast majority of water reabsorption occurs in the small intestine, which recovers an impressive 7800 mL. This efficiency is critical, as it prevents dehydration and ensures that valuable electrolytes are also reabsorbed. The remaining fluid, still substantial, then moves into the large intestine, or colon. Here, further water reabsorption takes place, with an additional 1250 mL being reclaimed. This final stage of water recovery is crucial for compacting waste material and forming solid feces.

The precision of this fluid management system is evident in the final output: typically, only about 150 mL of water is lost in feces each day. This represents a recovery rate of over 98% of the total fluid processed by the digestive system, underscoring the body’s commitment to fluid homeostasis. Disruptions in this delicate balance, such as those caused by infections, inflammatory bowel diseases, or malabsorption syndromes, can lead to significant fluid and electrolyte imbalances, manifesting as diarrhea or constipation. For example, severe diarrhea can rapidly lead to dehydration and electrolyte depletion, emphasizing the vital role of water reabsorption throughout the gastrointestinal tract.

In conclusion, the digestive system’s ability to manage vast quantities of fluid through precise secretion and reabsorption mechanisms is a testament to its evolutionary efficiency. From the initial intake of food and drink to the final excretion, every step is carefully regulated to maximize nutrient absorption while conserving vital water. Understanding this dynamic fluid balance is not only key to comprehending normal gastrointestinal function but also essential for diagnosing and treating conditions that compromise the body’s hydration and electrolyte status.