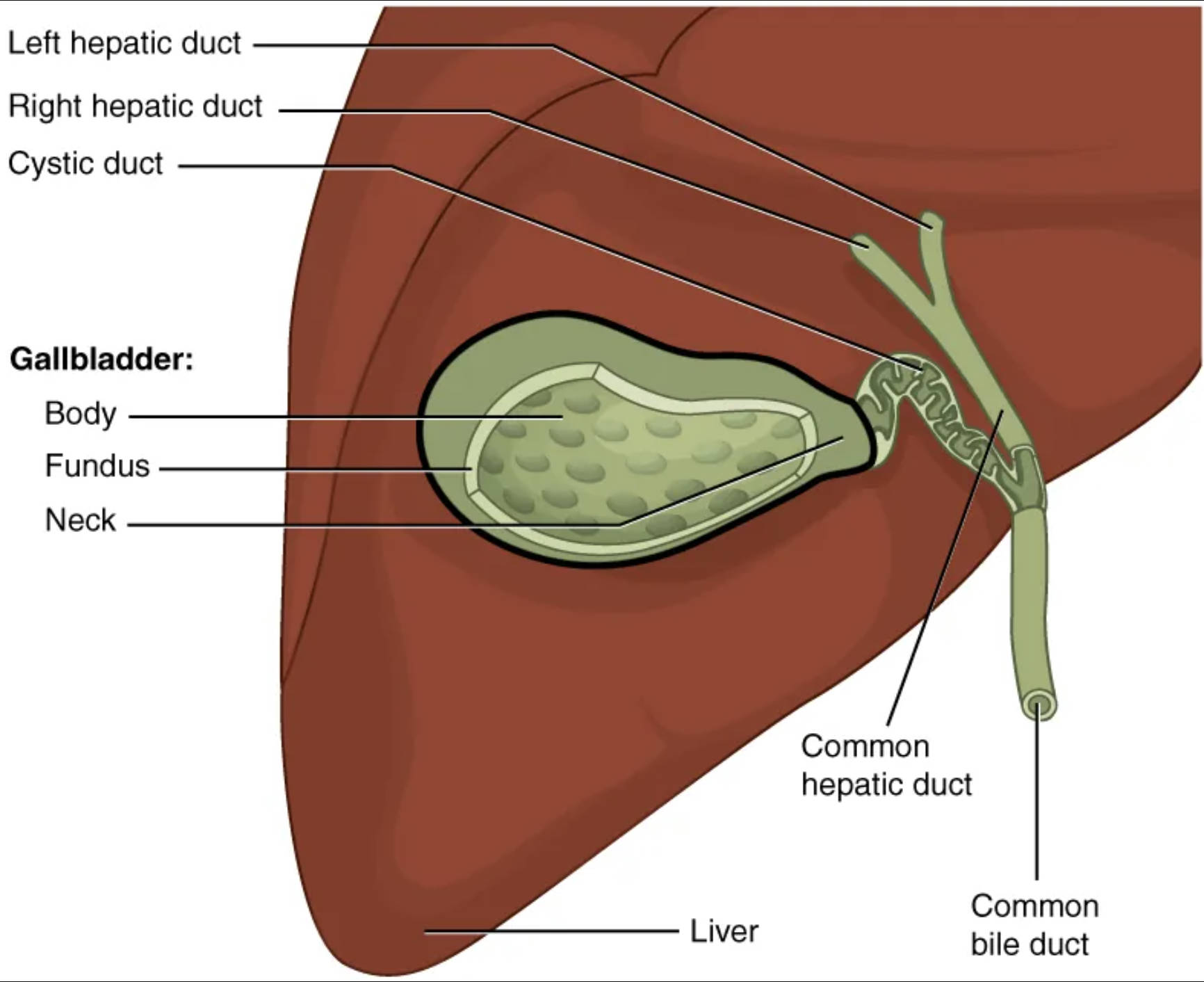

The gallbladder is a small, pear-shaped organ tucked just beneath the liver, playing a crucial, albeit often overlooked, role in digestion. This anatomical diagram provides a clear illustration of its structure and its intricate connections within the biliary system, highlighting how bile, essential for fat digestion, is stored, concentrated, and released. Exploring its specific parts and their relationships to the hepatic ducts and liver offers invaluable insight into the digestive process and the potential origins of common gastrointestinal issues.

Left hepatic duct: This duct collects bile produced by the left lobe of the liver. It merges with the right hepatic duct to form the common hepatic duct, transporting bile out of the liver.

Right hepatic duct: This duct collects bile produced by the right lobe of the liver. It joins with the left hepatic duct to create the common hepatic duct, facilitating bile drainage from the liver.

Cystic duct: This is a two-way duct that connects the gallbladder to the common hepatic duct. Bile flows into the gallbladder for storage and out of the gallbladder into the common bile duct when needed for digestion.

Body: The main, central portion of the gallbladder. This is the largest section where the majority of bile is stored and concentrated.

Fundus: The broad, rounded end of the gallbladder, extending inferiorly and anteriorly. It is typically the most inferior and distal part of the organ.

Neck: The tapered, narrow portion of the gallbladder that connects to the cystic duct. This area is prone to gallstone impaction due to its constricted lumen.

Common hepatic duct: Formed by the convergence of the left and right hepatic ducts, this duct carries bile from the liver. It eventually joins the cystic duct to form the common bile duct.

Common bile duct: This duct is formed by the union of the common hepatic duct and the cystic duct. It transports bile from both the liver and the gallbladder to the duodenum of the small intestine.

Liver: The largest internal organ, located in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen, responsible for producing bile. The liver is vital for numerous metabolic functions, including detoxification and nutrient processing.

The human digestive system is a complex network, and within it, the gallbladder holds a significant position despite its modest size. Its primary function is to serve as a reservoir for bile, a digestive fluid continuously produced by the liver. Bile is critical for the emulsification of fats in the small intestine, breaking down large lipid globules into smaller ones, thereby increasing their surface area for enzymatic digestion by lipases. Without adequate bile, the digestion and absorption of dietary fats and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) would be severely compromised.

Beyond mere storage, the gallbladder also plays a crucial role in concentrating bile. It achieves this by absorbing water and electrolytes from the bile, making the stored fluid significantly more potent than the bile directly secreted by the liver. This concentration mechanism ensures that a smaller volume of bile can be released to effectively digest a fatty meal. The release of bile is carefully regulated, primarily by the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK), which is secreted by the small intestine in response to the presence of fats and proteins. CCK stimulates the contraction of the gallbladder and relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi, allowing concentrated bile to flow into the duodenum.

The intricate network of ducts, known collectively as the biliary tree, facilitates the transport of bile. From the hepatic ducts within the liver to the common bile duct that empties into the duodenum, each segment ensures the directional flow of this vital fluid. The two-way nature of the cystic duct is particularly interesting, allowing bile to both enter the gallbladder for storage and exit when digestive demands arise. This elegant system ensures that bile is available precisely when and where it is needed, optimizing the digestive process.

Disruptions in this finely tuned system can lead to various medical conditions, with gallstones being one of the most common. Gallstones, or cholelithiasis, are hardened deposits of digestive fluid that can form in the gallbladder. They can range in size from a grain of sand to a golf ball and are typically composed of cholesterol or bilirubin. When gallstones obstruct the cystic duct or common bile duct, they can cause sudden, intense pain (biliary colic), inflammation of the gallbladder (cholecystitis), or more serious complications like pancreatitis or cholangitis. Symptoms often include pain in the upper right abdomen, nausea, vomiting, and sometimes jaundice if the common bile duct is blocked. Treatment options range from watchful waiting to medication, and often, surgical removal of the gallbladder (cholecystectomy) is necessary for recurrent or severe cases.

In summary, the gallbladder, though small, is an indispensable component of the digestive system, efficiently managing the storage and delivery of concentrated bile. Its anatomical structure, interconnected with the liver and biliary ducts, underscores its critical function in fat digestion and absorption. A clear understanding of the gallbladder’s role and the common issues that can affect it, such as gallstones, is paramount for maintaining digestive health and for the diagnosis and management of related medical conditions.