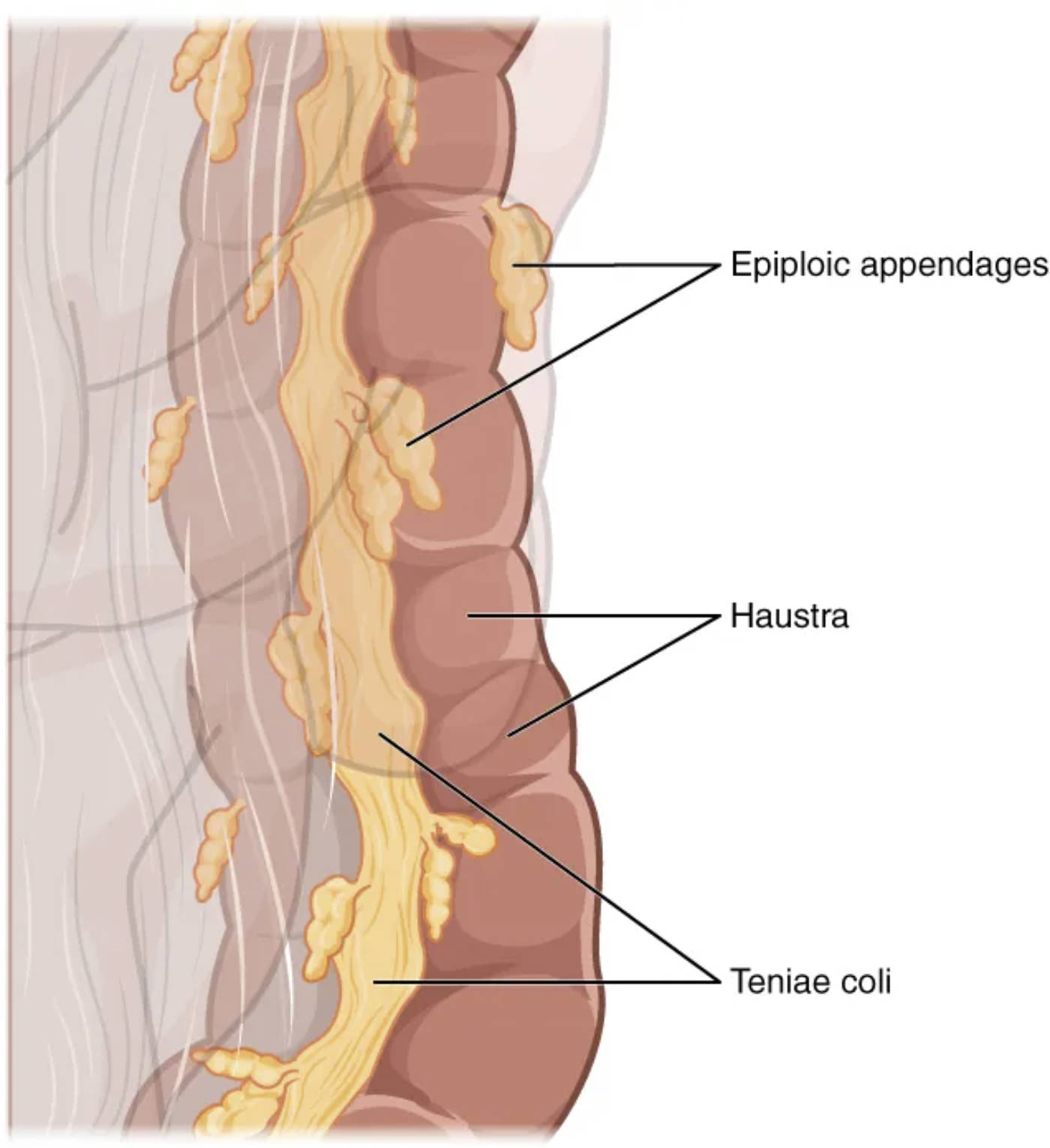

Explore the unique external anatomical features that characterize the large intestine, distinguishing it from other parts of the gastrointestinal tract. This article delves into the roles of the teniae coli, haustra, and epiploic appendages, explaining how these structures contribute to the colon’s specialized functions in water absorption, waste storage, and motility, providing a comprehensive understanding of its crucial role in digestive health.

Epiploic appendages: Also known as appendices epiploicae, these are small, fat-filled pouches of peritoneum that are attached to the outer surface of the colon. Their precise function is not entirely clear, but they are thought to play roles in immune function or lymphatic drainage.

Haustra: These are the sacculations or pouches that give the colon its characteristic segmented appearance. Formed by the contraction of the teniae coli, haustra allow the colon to expand and contract, facilitating the mixing of chyme and the absorption of water and electrolytes.

Teniae coli: These are three distinct, longitudinal bands of smooth muscle that run along the outer surface of the colon. Unlike the continuous muscular layer found in other parts of the digestive tract, the teniae coli are shorter than the colon itself, causing the wall to pucker and form the haustra.

The large intestine, a vital component of the digestive system, possesses several distinctive external anatomical features that set it apart from the small intestine. These unique characteristics are not merely superficial; they are integral to its specialized functions of water and electrolyte absorption, waste storage, and fecal elimination. The most prominent of these features include the teniae coli, haustra, and epiploic appendages, which collectively contribute to the colon’s macroscopic appearance and its operational efficiency.

These anatomical specializations allow the large intestine to efficiently transform liquid chyme into solid feces, a process critical for maintaining the body’s fluid balance. The muscular arrangements, in particular, facilitate a type of motility known as haustral churning, which helps mix the luminal contents and ensures thorough contact with the absorptive mucosal surface. Furthermore, the presence of structures like the epiploic appendages, though their exact function is still debated, adds to the unique macroscopic identity of the colon.

Understanding these external features is essential for both medical professionals and anyone interested in the intricacies of human anatomy. They serve as reliable landmarks during surgical procedures and diagnostic imaging, and their alterations can sometimes indicate underlying pathological conditions. The image above provides a clear visual representation of these key anatomical structures, offering a foundational insight into the specialized design of the large intestine.

Teniae Coli: The Defining Muscular Bands

One of the most characteristic features of the colon is the presence of the teniae coli. These are three discrete, ribbon-like bands of longitudinal smooth muscle that run along the outer surface of the ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon. Unlike the continuous outer longitudinal muscle layer found in most other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, the muscle fibers in the large intestine’s longitudinal layer are concentrated into these three distinct bands.

The teniae coli are shorter in length than the colon wall itself. This disparity in length causes the underlying colonic wall to pucker into a series of sacculations or pouches, which are known as the haustra. The rhythmic contractions of the teniae coli are crucial for various colonic movements, including haustral churning and mass movements, which are essential for mixing the contents and propelling feces.

Haustra: The Sacculated Pouches of the Colon

The haustra are the prominent, segmental pouches or sacculations that give the colon its characteristic “lumpy” appearance. These are formed due to the tonic contraction of the teniae coli, which effectively shortens the colon’s length, causing the intervening areas of the wall to bulge outwards.

The haustra serve several important functions:

- Mixing (Haustral Churning): The rhythmic contractions and relaxations of individual haustra facilitate the mixing of chyme, ensuring that all parts of the fecal matter come into contact with the mucosal lining. This process enhances the absorption of water and electrolytes.

- Storage: Haustra provide temporary storage for fecal matter, allowing for a slower transit time within the colon. This extended dwell time is crucial for maximizing water reabsorption and compacting feces.

- Propulsion: While primarily involved in mixing, the progressive contraction of adjacent haustra contributes to the slow forward movement of colonic contents.

Epiploic Appendages: Fatty Peritoneal Pouches

Epiploic appendages, also known as appendices epiploicae, are small, yellowish, fat-filled pouches of peritoneum that project from the outer surface of the colon, typically along the teniae coli. These structures vary in size and number among individuals and along different segments of the colon.

While their exact physiological function remains somewhat elusive, several theories propose their roles:

- Immune Function: Some theories suggest they may have a role in the immune system due to their vascularization and the presence of immune cells.

- Lymphatic Drainage: They might also be involved in lymphatic drainage or serve as protective cushions.

- Clinical Significance: Clinically, epiploic appendages can become inflamed (epiploic appendagitis) or undergo torsion, mimicking symptoms of appendicitis or diverticulitis.

In conclusion, the teniae coli, haustra, and epiploic appendages are not merely anatomical curiosities but integral components of the large intestine’s structure and function. The unique arrangement of the teniae coli creates the characteristic haustra, which are essential for mixing contents and facilitating water absorption. Meanwhile, the epiploic appendages, though their precise role is still under investigation, add to the distinct macroscopic appearance of the colon. Together, these features underscore the large intestine’s specialized adaptations for its critical role in the final stages of digestion and maintaining physiological balance.