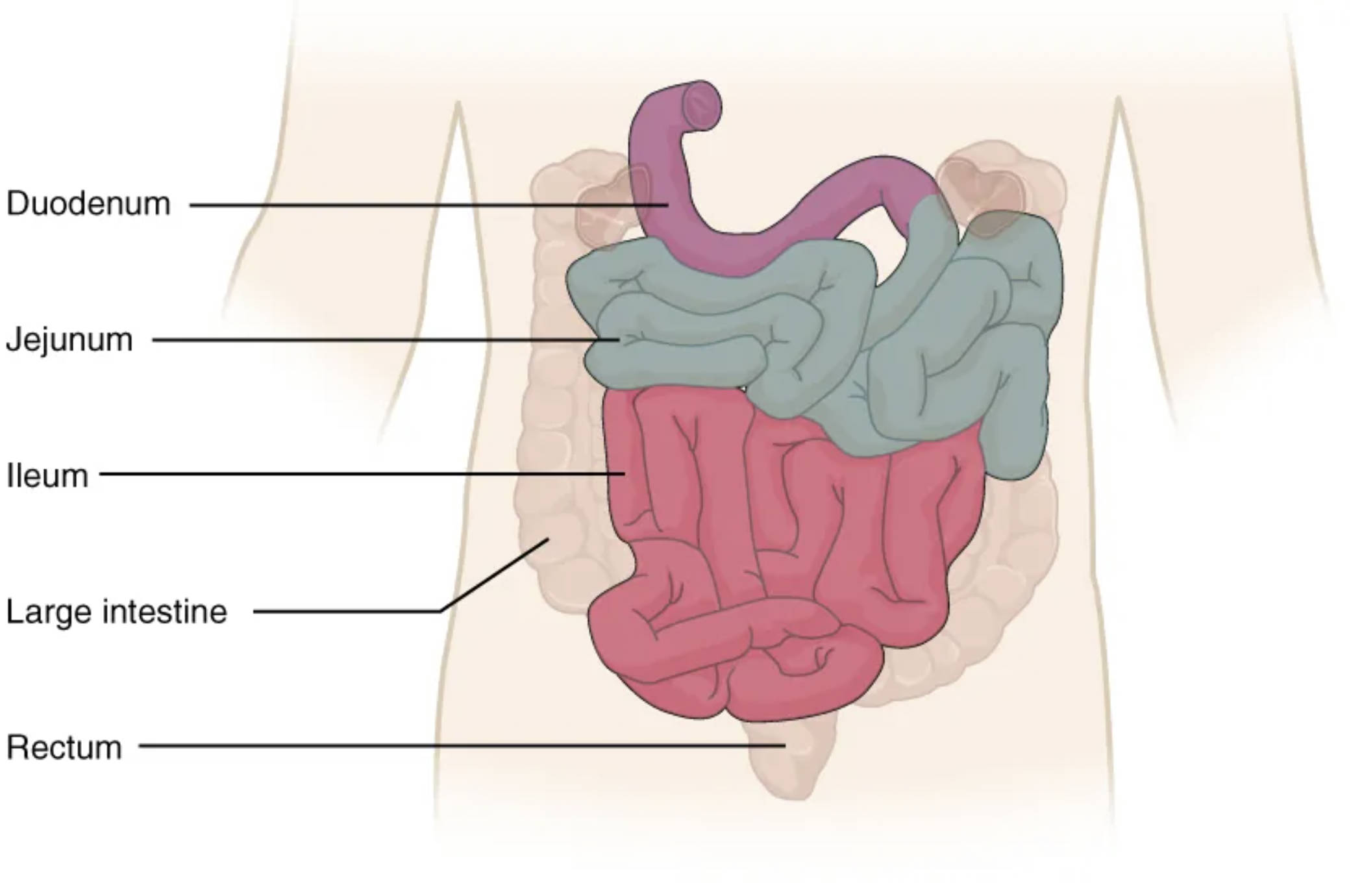

Dive into the intricate world of the small intestine, a vital organ responsible for the lion’s share of nutrient absorption. This comprehensive guide explores its three distinct regions—the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum—detailing their unique anatomical features and crucial roles in the digestive process. Understanding these segments is key to appreciating the efficiency of human digestion.

Duodenum: This is the first and shortest section of the small intestine, directly receiving partially digested food (chyme) from the stomach. It is C-shaped and plays a crucial role in neutralizing stomach acid and initiating further digestion with the help of bile and pancreatic enzymes.

Jejunum: Following the duodenum, the jejunum is the middle segment of the small intestine and typically makes up about two-fifths of its total length. This section is primarily responsible for the bulk of nutrient absorption, particularly carbohydrates and proteins, due to its specialized internal lining.

Ileum: The ileum is the final and longest section of the small intestine, connecting to the large intestine at the ileocecal valve. Its main function is to absorb vitamin B12, bile salts, and any remaining nutrients that were not absorbed in the jejunum.

Large intestine: While not part of the small intestine, the large intestine is the next major segment of the digestive tract after the ileum. It is primarily involved in absorbing water and electrolytes, forming feces, and housing beneficial gut bacteria.

Rectum: This is the final section of the large intestine, serving as a temporary storage site for feces before defecation. The rectum signals the brain when it is full, initiating the urge to expel waste.

The small intestine, a coiled tube measuring approximately 6 to 7 meters in length in adults, is the primary site for chemical digestion and nutrient absorption within the human body. Despite its name, which refers to its smaller diameter compared to the large intestine, its extensive length and specialized internal structure provide an enormous surface area for efficient nutrient uptake. This remarkable organ is strategically positioned between the stomach and the large intestine, orchestrating a complex array of digestive processes.

Functionally, the small intestine is a powerhouse where the breakdown of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats into their absorbable components is completed. This is achieved through the coordinated action of enzymes from the pancreas, bile from the liver, and enzymes secreted by the small intestine itself. The absorbed nutrients, including amino acids, simple sugars, fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals, then pass into the bloodstream or lymphatic system to be distributed throughout the body.

The efficiency of nutrient absorption in the small intestine is largely attributed to its unique anatomical adaptations. The inner lining, or mucosa, is not smooth but features numerous folds, villi, and microvilli, collectively known as the brush border. These structures dramatically increase the surface area available for contact with digested food particles. Without these specialized adaptations, the absorption of essential nutrients would be significantly compromised, leading to various malabsorption syndromes.

The small intestine is anatomically divided into three distinct segments, each with specialized roles in digestion and absorption: the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum. These segments work sequentially to process chyme received from the stomach, extract vital nutrients, and propel the remaining undigested material toward the large intestine.

Duodenum: The Initial Processing Hub

The duodenum, the shortest segment, begins immediately after the pyloric sphincter of the stomach. Its C-shaped curve cradles the head of the pancreas, and it is here that stomach acid is neutralized by bicarbonate secreted from the pancreas. Furthermore, the duodenum receives bile from the gallbladder and liver, crucial for emulsifying fats, and a rich array of digestive enzymes from the pancreas, including amylase for carbohydrates, lipase for fats, and proteases for proteins. This initial segment is critical for preparing the chyme for subsequent absorption.

Jejunum: The Primary Absorption Site

Following the duodenum, the jejunum is where the majority of nutrient absorption takes place. Its walls are rich in highly developed circular folds and villi, maximizing its absorptive capacity. Here, the final breakdown products of carbohydrates (monosaccharides), proteins (amino acids and small peptides), and fats (fatty acids and glycerol) are absorbed into the bloodstream. The jejunum’s extensive vascularization supports this high metabolic demand.

Ileum: Final Absorption and Immune Surveillance

The ileum, the longest segment, extends from the jejunum to the ileocecal valve, which separates it from the large intestine. While some nutrient absorption continues here, its primary role is the absorption of specific substances, most notably vitamin B12 and bile salts. The ileum also houses Peyer’s patches, which are aggregates of lymphoid tissue important for immune surveillance, protecting the body from pathogens that may enter with food.

In conclusion, the small intestine stands as a marvel of biological engineering, meticulously designed to extract maximum nutrition from our food. Its three interconnected regions—duodenum, jejunum, and ileum—each contribute unique structural and functional specializations to the digestive process. From neutralizing stomach acid and breaking down macronutrients to absorbing essential vitamins and providing immune defense, the small intestine’s role is indispensable for maintaining overall health and well-being. A thorough understanding of its anatomy and physiology is fundamental to comprehending the intricacies of human digestion.