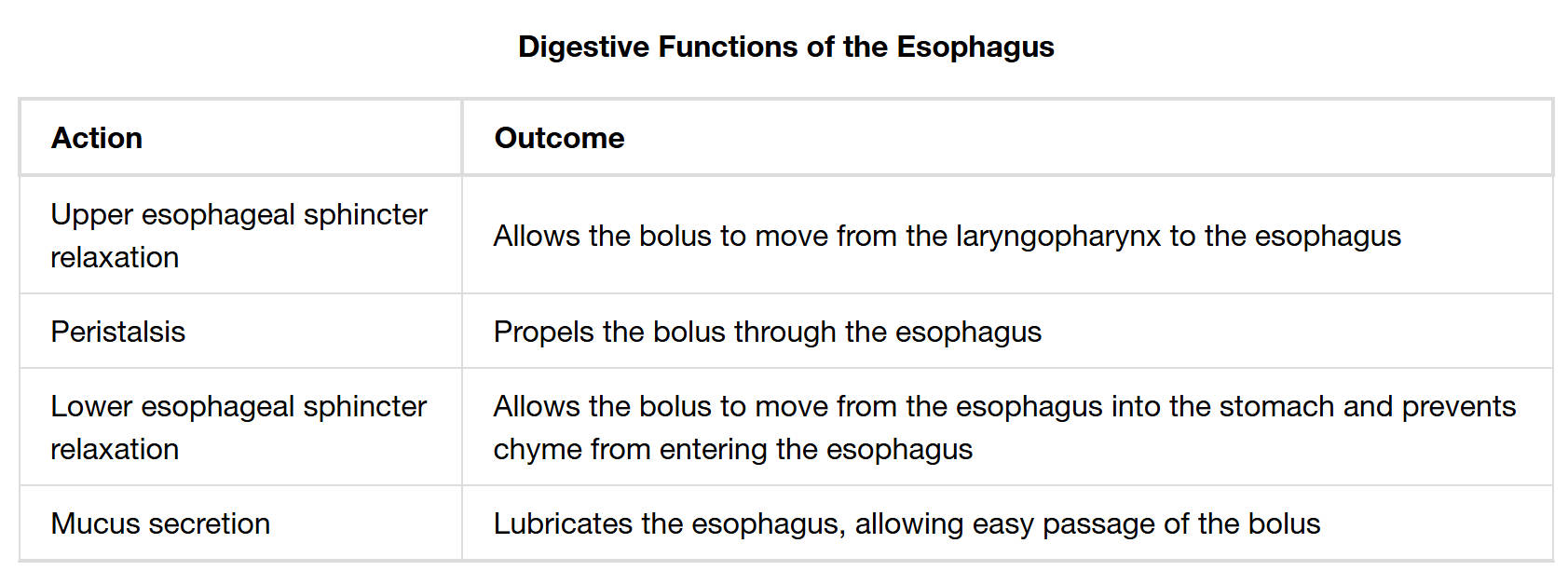

Explore the essential digestive functions of the esophagus, a muscular tube critical for food transport. Learn about the coordinated actions of sphincter relaxation, peristalsis, and mucus secretion that ensure the smooth and controlled movement of a food bolus from the pharynx to the stomach, preventing reflux and initiating the next stage of digestion.

The esophagus, often perceived simply as a passive tube, is in fact a highly active and crucial component of the digestive system. Its primary role is to efficiently and safely transport ingested food from the pharynx to the stomach, a process known as deglutition or swallowing. This seemingly straightforward action involves a complex interplay of muscular contractions and relaxations, along with protective secretions, all orchestrated to prevent aspiration into the lungs and ensure unidirectional movement of the food bolus.

Upper esophageal sphincter relaxation: This action allows the food bolus to move from the laryngopharynx into the esophagus. The upper esophageal sphincter (UES) typically remains contracted at rest, preventing air from entering the esophagus during breathing.

Peristalsis: This is a series of wave-like muscular contractions that sequentially move along the esophageal tube. Peristalsis actively propels the food bolus through the esophagus, ensuring its efficient and unidirectional transport towards the stomach, regardless of gravity.

Lower esophageal sphincter relaxation: This action allows the food bolus to move from the esophagus into the stomach. Concurrently, the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) prevents the acidic chyme from the stomach from re-entering the esophagus, protecting the sensitive esophageal lining from reflux.

Mucus secretion: The esophagus secretes mucus throughout its lining. This provides essential lubrication to the esophageal walls, facilitating the easy and smooth passage of the food bolus, thereby reducing friction and potential damage.

The Esophagus: A Coordinated Conduit for Digestion

The journey of food through the human digestive system begins long before it reaches the stomach, with the esophagus playing a critical role in the initial transport phase. This muscular tube acts as a precise conduit, ensuring that the processed food bolus from the mouth and pharynx is efficiently delivered to the stomach. The seamless execution of these functions is vital for preventing choking, protecting the delicate esophageal lining, and setting the stage for subsequent digestive processes.

The key digestive functions of the esophagus are a testament to its specialized design:

- Controlled Entry: The relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter facilitates the entry of the food bolus from the pharynx into the esophagus.

- Propulsion: Peristalsis, a rhythmic, involuntary muscular contraction, actively pushes the bolus down the length of the esophagus.

- Controlled Exit and Reflux Prevention: The lower esophageal sphincter relaxes to allow food into the stomach and then contracts to prevent acidic chyme from flowing back into the esophagus.

- Lubrication: Mucus secretion ensures a smooth passage, minimizing friction and protecting the esophageal lining.

The entire process, from the voluntary act of initiating a swallow to the involuntary actions within the esophagus, is remarkably coordinated. Once the bolus enters the esophagus, the UES closes to prevent reflux into the pharynx, and primary peristaltic waves are initiated. These powerful contractions, coupled with the lubricating action of mucus, ensure rapid transit of the food. The timely relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter is crucial, allowing the bolus to enter the stomach while maintaining a tight seal afterward. Dysfunction in any of these mechanisms can lead to significant clinical conditions. For example, a failure of the LES to function correctly is the primary cause of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), characterized by heartburn and potential damage to the esophageal lining. Similarly, disorders of peristalsis, such as esophageal spasms or achalasia, can lead to severe dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and chest pain, underscoring the delicate balance required for proper esophageal function.

In conclusion, the esophagus is far from a passive tube; it is an active and dynamic organ whose precisely coordinated functions are fundamental to the initial stages of digestion. The synchronized relaxation of its sphincters, the powerful waves of peristalsis, and the constant lubrication provided by mucus secretion collectively ensure the efficient and safe transport of food. Understanding these vital mechanisms is crucial for appreciating digestive health and for the diagnosis and management of common esophageal disorders.