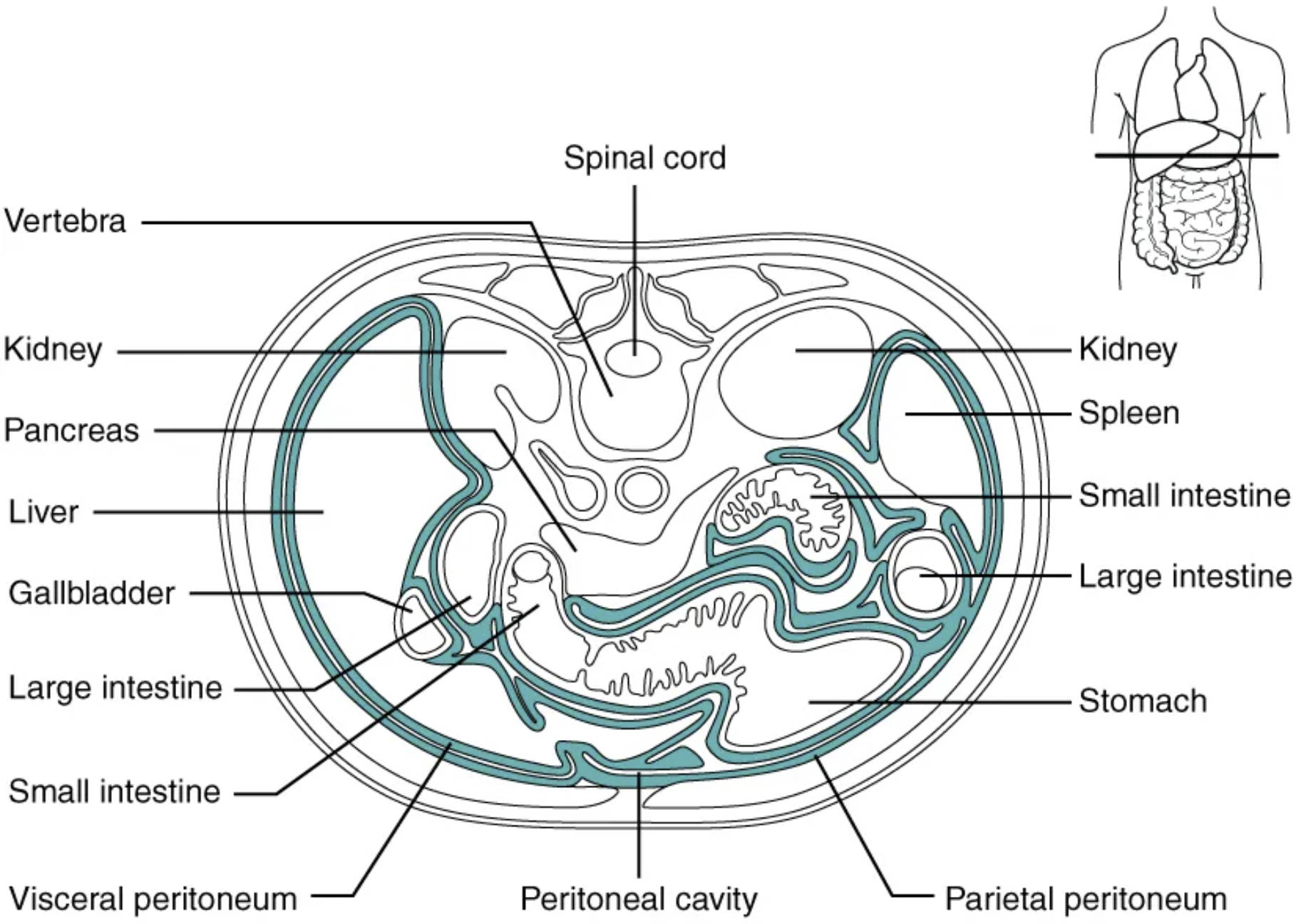

The human abdomen houses vital organs, intricately organized and protected by specialized membranes. This article explores a cross-sectional view of the abdomen, highlighting the complex relationship between various abdominal organs and the peritoneum. Understanding this anatomical arrangement is crucial for comprehending organ function, disease processes, and surgical approaches.

Spinal cord: This is a vital part of the central nervous system, extending from the brainstem down the back. It carries nerve signals throughout the body, controlling movement, sensation, and autonomic functions, including those of the abdominal organs.

Vertebra: These are the individual bones that make up the spinal column, providing structural support to the body and protecting the spinal cord. In a cross-section, a vertebra shows its central body and posterior arch, enclosing the spinal canal.

Kidney (left): One of two bean-shaped organs located on either side of the spine, filtering blood to remove waste products and excess water. It plays a crucial role in maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance, and producing urine.

Pancreas: An elongated gland located posterior to the stomach, performing both exocrine and endocrine functions. It produces digestive enzymes that are secreted into the small intestine and hormones like insulin and glucagon, which regulate blood sugar.

Liver: The largest internal organ, located in the upper right abdomen, performing a multitude of metabolic functions. These include detoxification, protein synthesis, and the production of bile for fat digestion.

Gallbladder: A small, pear-shaped organ tucked beneath the liver that stores and concentrates bile produced by the liver. It releases bile into the small intestine to aid in the digestion and absorption of fats.

Large intestine (transverse colon section): The final section of the gastrointestinal tract, primarily responsible for absorbing water and electrolytes and forming feces. Its convoluted path through the abdomen is clearly visible in this cross-section.

Small intestine (multiple loops): A long, coiled tube extending from the stomach to the large intestine, where most chemical digestion and nutrient absorption occur. Its numerous loops are enveloped by the peritoneum, allowing for movement and extensive surface area for absorption.

Visceral peritoneum: This is the inner layer of the peritoneum, directly covering the surfaces of the abdominal organs. It secretes serous fluid, which reduces friction between organs and facilitates their movement within the abdominal cavity.

Peritoneal cavity: The potential space between the parietal and visceral layers of the peritoneum, normally containing a small amount of serous fluid. This fluid allows the abdominal organs to slide past one another without friction during digestion and movement.

Parietal peritoneum: This is the outer layer of the peritoneum, lining the internal surface of the abdominal and pelvic walls. It is sensitive to pain, temperature, and touch, differing from the visceral peritoneum which has limited sensory innervation.

Stomach: A J-shaped organ located in the upper left abdomen, playing a key role in the initial stages of protein digestion. It churns food and mixes it with gastric juices, forming chyme, before passing it to the small intestine.

Large intestine (descending colon section): Another section of the large intestine, responsible for further water absorption and compaction of waste. It descends along the left side of the abdominal cavity towards the rectum.

Small intestine (jejunal/ileal loops): These central sections of the small intestine continue the processes of digestion and nutrient absorption. Their extensive coiling maximizes the surface area available for these vital functions.

Spleen: An organ located in the upper left abdomen, playing a crucial role in the immune system by filtering blood and removing old red blood cells. It also serves as a reservoir for blood.

Kidney (right): The other kidney, mirroring the left one in function, maintaining the body’s fluid balance and filtering waste. Both kidneys are retroperitoneal, meaning they lie behind the peritoneum.

The intricate architecture of the human abdomen is a testament to biological design, housing a multitude of vital organs essential for life. A cross-sectional view, such as the one presented, offers an unparalleled perspective into the spatial relationships and protective mechanisms at play within this crucial body cavity. Central to this organization is the peritoneum, a serous membrane that lines the abdominal cavity and envelops many of its organs. This complex arrangement not only provides structural support but also facilitates movement and protects against friction.

Understanding the peritoneum’s dual layers—the parietal and visceral peritoneum—and the potential space between them, known as the peritoneal cavity, is fundamental to comprehending abdominal anatomy. These layers are not merely passive linings; they play active roles in immune defense and fluid balance. The organs within the abdomen can be broadly categorized based on their relationship with the peritoneum:

- Intraperitoneal organs: Organs almost completely covered by the visceral peritoneum (e.g., stomach, spleen, most of the small intestine).

- Retroperitoneal organs: Organs located posterior to the peritoneum (e.g., kidneys, pancreas, parts of the large intestine).

- Infraperitoneal (or subperitoneal) organs: Organs located inferior to the peritoneum (e.g., bladder, lower rectum).

This distinct classification has significant implications for surgical approaches and the spread of disease within the abdominal cavity.

The Peritoneum: A Protective and Lubricating Membrane

The peritoneum is a double-layered serous membrane that lines the abdominal cavity, providing both protection and lubrication for the abdominal organs. The parietal peritoneum forms the outer lining, adhering to the abdominal wall, while the visceral peritoneum directly encases the organs within the cavity. Between these two layers lies the peritoneal cavity, a potential space typically containing a small amount of serous fluid. This fluid acts as a lubricant, allowing the organs to move smoothly against each other and the abdominal wall without friction during activities such as digestion and breathing. The peritoneum also forms folds and extensions, such as the mesentery and omenta, which suspend and support organs, providing pathways for blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels.

Key Abdominal Organs and Their Peritoneal Relationships

The cross-sectional view vividly displays several vital abdominal organs and their relationships with the peritoneum. Organs like the liver and spleen are prominently positioned, performing critical functions in metabolism, detoxification, and immune surveillance. The stomach, a key player in digestion, is largely intraperitoneal, allowing for its significant expansion and contraction. The small intestine, with its numerous coiled loops, and portions of the large intestine are also mostly intraperitoneal, facilitating their extensive movements required for digestion and absorption. In contrast, organs such as the kidneys and pancreas are retroperitoneal, situated behind the parietal peritoneum. This anatomical distinction influences how these organs are accessed surgically and how infections or fluid collections may spread within the abdominal cavity.

The Role of Spinal Cord and Vertebrae in Abdominal Support

Beyond the soft tissues and organs, the cross-section also highlights the fundamental skeletal and neurological components that underpin abdominal anatomy. The vertebra, part of the spinal column, provides crucial posterior support and protection to the abdominal cavity and its contents. Enclosed within the vertebrae, the spinal cord serves as a central communication pathway, transmitting signals between the brain and the abdominal organs. Nerves originating from the spinal cord innervate these organs, regulating their functions, from peristalsis in the intestines to glandular secretions. This integrated system of skeletal support and neural control ensures the coordinated function and overall well-being of the abdominal organs, emphasizing the body’s holistic design.

In conclusion, a cross-sectional perspective of the abdomen unveils the remarkable complexity and organization of its internal structures. The peritoneum, with its parietal and visceral layers, plays a fundamental role in encasing, protecting, and lubricating the organs, enabling their crucial functions. From the digestive powerhouses like the liver, stomach, and intestines, to the excretory and endocrine roles of the kidneys and pancreas, each organ is strategically positioned within this intricate abdominal landscape. Understanding these spatial relationships, along with the foundational support provided by the vertebrae and the neurological control from the spinal cord, is essential for a comprehensive grasp of human anatomy and its implications for health and disease.