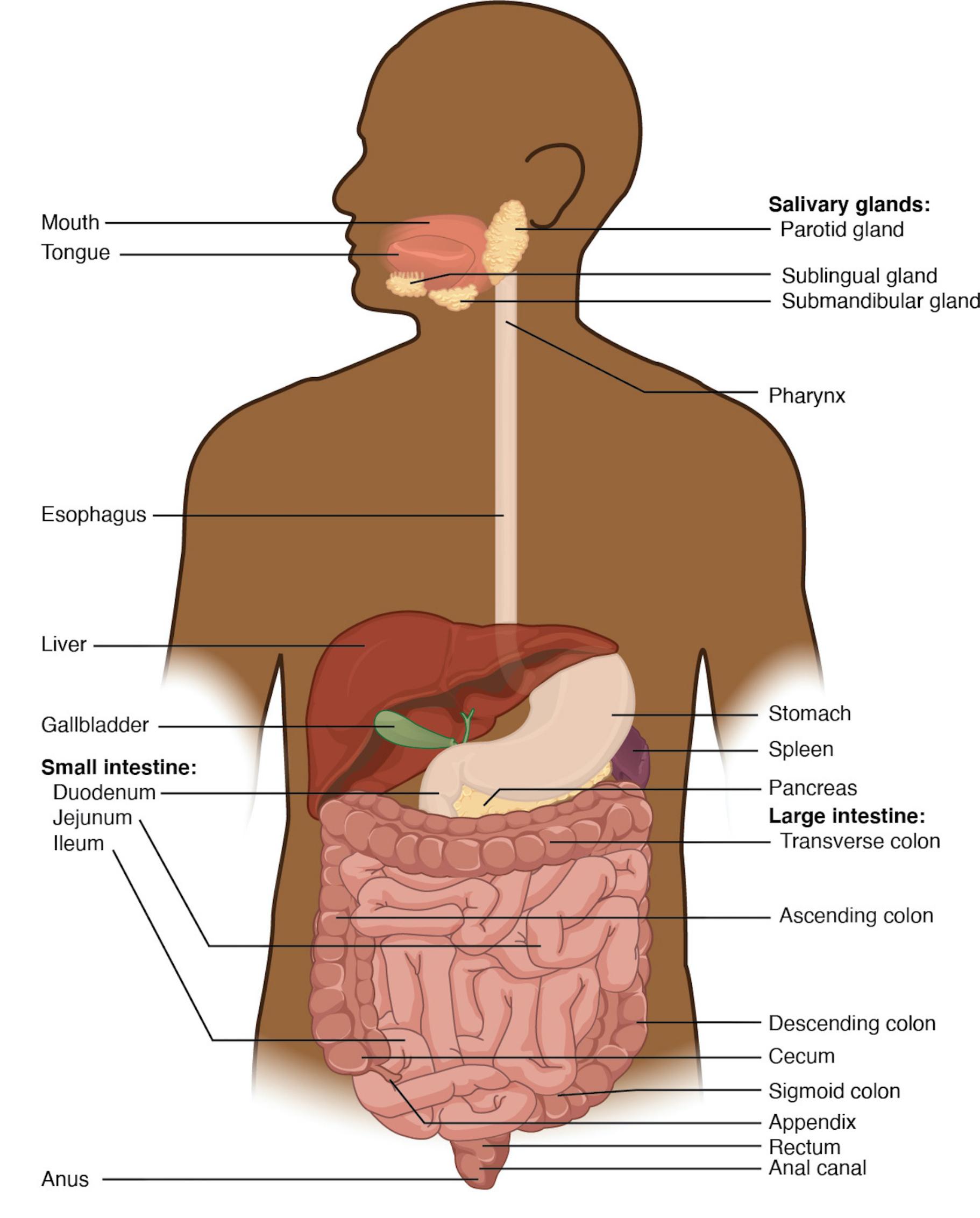

Explore the intricate components of the digestive system, a complex network of organs responsible for breaking down food, absorbing nutrients, and eliminating waste. This vital system ensures that our bodies receive the energy and building blocks necessary for life, impacting overall health and well-being.

Understanding the Components of the Digestive System Diagram

Mouth: The entry point of the digestive tract, responsible for the initial mechanical breakdown of food through chewing (mastication) and chemical digestion with salivary enzymes. It forms a food bolus that is ready for swallowing.

Tongue: A muscular organ located in the mouth, crucial for tasting, manipulating food during chewing, and initiating the swallowing process. It helps mix food with saliva and forms the bolus.

Salivary glands: These glands produce saliva, which moistens food, aids in swallowing, and initiates carbohydrate and lipid digestion through enzymes like amylase and lipase. The three major pairs are the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands.

Parotid gland: The largest of the salivary glands, located just below and in front of the ear. It primarily produces serous saliva rich in amylase, essential for the initial breakdown of starches.

Sublingual gland: Situated under the tongue, this gland produces mostly mucous saliva. Its secretions contribute to moistening and lubricating food.

Submandibular gland: Located beneath the jaw, this gland produces a mixed serous and mucous saliva. It accounts for the majority of saliva production and contributes both amylase and mucus.

Pharynx: The throat, a muscular tube that connects the nasal and oral cavities to the larynx and esophagus. It serves as a common passageway for both food and air, playing a key role in swallowing.

Esophagus: A muscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach. It transports food via rhythmic muscular contractions called peristalsis, ensuring food moves efficiently towards the stomach.

Liver: The largest internal organ, with a multitude of metabolic functions, including producing bile (essential for fat digestion), detoxifying harmful substances, and metabolizing carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. It plays a central role in nutrient processing.

Gallbladder: A small, pear-shaped organ located beneath the liver. Its primary function is to store and concentrate bile produced by the liver, releasing it into the small intestine when fats are present.

Stomach: A muscular, J-shaped organ that receives food from the esophagus. It churns food mechanically and chemically digests proteins with gastric acid and pepsin, converting the food into a semi-liquid mixture called chyme.

Spleen: An organ of the lymphatic system, located in the upper left abdomen. While not directly part of the digestive tract, it plays a role in filtering blood, removing old red blood cells, and immune function.

Pancreas: A gland located behind the stomach with both exocrine and endocrine functions. Its exocrine function involves producing digestive enzymes (amylase, lipase, proteases) that are released into the small intestine, and its endocrine function produces hormones like insulin and glucagon.

Small intestine: The primary site for chemical digestion and nutrient absorption, a long, coiled tube divided into three segments. Its extensive surface area, enhanced by villi and microvilli, maximizes nutrient uptake.

Duodenum: The first and shortest segment of the small intestine, receiving chyme from the stomach and digestive enzymes from the pancreas and bile from the gallbladder. It is a major site of chemical digestion.

Jejunum: The middle segment of the small intestine, where the majority of nutrient absorption occurs. Its rich blood supply and numerous folds make it highly efficient at absorbing digested carbohydrates and proteins.

Ileum: The final segment of the small intestine, primarily responsible for absorbing vitamin B12, bile salts, and any remaining nutrients. It connects to the large intestine at the ileocecal valve.

Large Intestine: A wider, shorter tube than the small intestine, responsible for absorbing water and electrolytes from indigestible food matter and forming feces. It also houses beneficial gut bacteria.

Transverse colon: The middle section of the large intestine, running horizontally across the upper abdomen. It continues the process of water absorption and waste consolidation.

Ascending colon: The first section of the large intestine, extending upwards from the cecum on the right side of the abdomen. It primarily absorbs remaining water and electrolytes.

Descending colon: The section of the large intestine that travels downwards on the left side of the abdomen. It stores feces that will eventually be emptied into the rectum.

Cecum: A pouch-like beginning of the large intestine, located in the lower right abdomen. It receives undigested food material from the ileum.

Sigmoid colon: The S-shaped final section of the large intestine, connecting the descending colon to the rectum. It stores feces before defecation.

Appendix: A small, finger-shaped pouch projecting from the cecum. Its exact function is unclear, but it may play a role in immune function or act as a safe house for beneficial gut bacteria.

Rectum: The final section of the large intestine, serving as a temporary storage site for feces before elimination. It signals the urge to defecate when distended.

Anal canal: The terminal part of the large intestine, extending from the rectum to the anus. It contains internal and external anal sphincters that control the release of feces.

Anus: The external opening at the end of the digestive tract, through which feces are eliminated from the body. It is controlled by the anal sphincters.

The human digestive system is an extraordinarily complex and efficient network of organs working in concert to transform the food we eat into the nutrients our bodies need. This vital system, extending from the mouth to the anus, performs a series of intricate mechanical and chemical processes to break down macromolecules into absorbable smaller units, extract essential vitamins and minerals, and eliminate indigestible waste. Without a functioning digestive system, the body would quickly succumb to malnutrition, highlighting its fundamental role in sustaining life and overall health.

The journey of digestion begins even before the first bite, with the sight, smell, or thought of food stimulating salivary glands. Once food enters the mouth, mechanical chewing and enzymatic action initiate the breakdown of carbohydrates and fats. From there, food travels through the pharynx and esophagus to the stomach, where powerful muscular contractions and strong acids further break down proteins. The partially digested food, now a liquid called chyme, then moves into the small intestine, the primary site for the absorption of nearly all nutrients.

The small intestine’s remarkable efficiency in nutrient absorption is supported by accessory organs: the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. The liver produces bile, stored in the gallbladder, which aids in fat digestion. The pancreas secretes a cocktail of powerful digestive enzymes and bicarbonate to neutralize stomach acid. Finally, the large intestine absorbs water and electrolytes, consolidating indigestible material into feces for elimination. Every component, from the smallest gland to the longest intestinal segment, plays an integral role in this life-sustaining process, underscoring the delicate balance required for optimal digestive health.

- The digestive system breaks down food and absorbs nutrients.

- It extends from the mouth to the anus.

- Accessory organs (liver, gallbladder, pancreas) support digestion.

- The small intestine is the main site of nutrient absorption.

The Journey Through the Alimentary Canal

The digestive process commences in the mouth, where teeth provide mechanical breakdown (mastication) and saliva, secreted by the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands, begins chemical digestion of carbohydrates (via amylase) and some fats (via lingual lipase). The tongue aids in forming a food bolus, which is then voluntarily swallowed, passing through the pharynx, a common passageway for food and air. From the pharynx, the bolus is propelled into the esophagus, a muscular tube that utilizes rhythmic, wave-like contractions called peristalsis to move food downwards towards the stomach.

Upon reaching the stomach, food undergoes further mechanical churning and intense chemical digestion. The stomach lining secretes gastric juice, a highly acidic solution containing hydrochloric acid and pepsin. Hydrochloric acid denatures proteins and activates pepsin, an enzyme that initiates protein digestion. The muscular contractions of the stomach thoroughly mix the food with gastric juices, transforming it into a semi-liquid, acidic mixture called chyme, which is then gradually released into the small intestine through the pyloric sphincter.

The small intestine, an incredibly long and coiled tube, is the principal site for nutrient absorption. It is divided into three segments: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. In the duodenum, chyme mixes with bile from the gallbladder (produced by the liver) and a rich array of digestive enzymes from the pancreas. Bile emulsifies fats, while pancreatic enzymes break down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats into their absorbable monomers (monosaccharides, amino acids, fatty acids, and glycerol). The jejunum and ileum, with their vast surface area enhanced by villi and microvilli, are specialized for absorbing these digested nutrients into the bloodstream and lymphatic system.

The Role of Accessory Organs

While food does not pass directly through them, the accessory organs—the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas—are indispensable for efficient digestion. The liver, the largest internal organ, performs numerous vital functions, including the synthesis of bile. Bile, a yellowish-green fluid, is crucial for the emulsification of dietary fats in the small intestine, breaking them down into smaller droplets that are more accessible to pancreatic lipase. The gallbladder serves as a storage and concentration reservoir for bile, releasing it into the duodenum upon stimulation by the presence of fat.

The pancreas is a dual-function gland. Its exocrine function is directly digestive, producing a potent cocktail of digestive enzymes (pancreatic amylase, lipase, trypsin, chymotrypsin) that are secreted into the duodenum. These enzymes are responsible for the bulk of carbohydrate, fat, and protein digestion. Additionally, the pancreas produces bicarbonate, which neutralizes the acidic chyme entering from the stomach, creating an optimal pH environment for intestinal and pancreatic enzymes to function effectively. The endocrine function of the pancreas involves producing hormones like insulin and glucagon, which regulate blood glucose levels.

The Final Stages: Large Intestine and Elimination

After nutrient absorption is largely complete in the small intestine, the remaining indigestible food matter, along with water and electrolytes, passes into the large intestine. The large intestine consists of the cecum (with the appendix attached), ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum. Its primary functions are the absorption of residual water and electrolytes, the compaction of waste material into feces, and the housing of a vast and diverse community of beneficial gut bacteria, which ferment some indigestible carbohydrates and synthesize certain vitamins (e.g., Vitamin K).

The final stage of digestion involves the temporary storage of feces in the rectum, followed by their elimination from the body through the anal canal and anus, a process known as defecation. The internal and external anal sphincters, under involuntary and voluntary control respectively, regulate this process. The efficiency and health of the entire digestive system are profoundly linked to overall well-being, influencing everything from energy levels and immune function to mental health.

Conclusion

The digestive system is a marvel of biological engineering, meticulously breaking down complex food molecules, extracting life-sustaining nutrients, and efficiently eliminating waste. From the mechanical and chemical processes initiated in the mouth to the crucial absorption in the small intestine and the final compaction in the large intestine, each organ plays a critical, interconnected role. A holistic understanding of this vital system is not only fundamental to human physiology but also essential for recognizing and addressing the myriad of digestive disorders that can significantly impact health and quality of life.