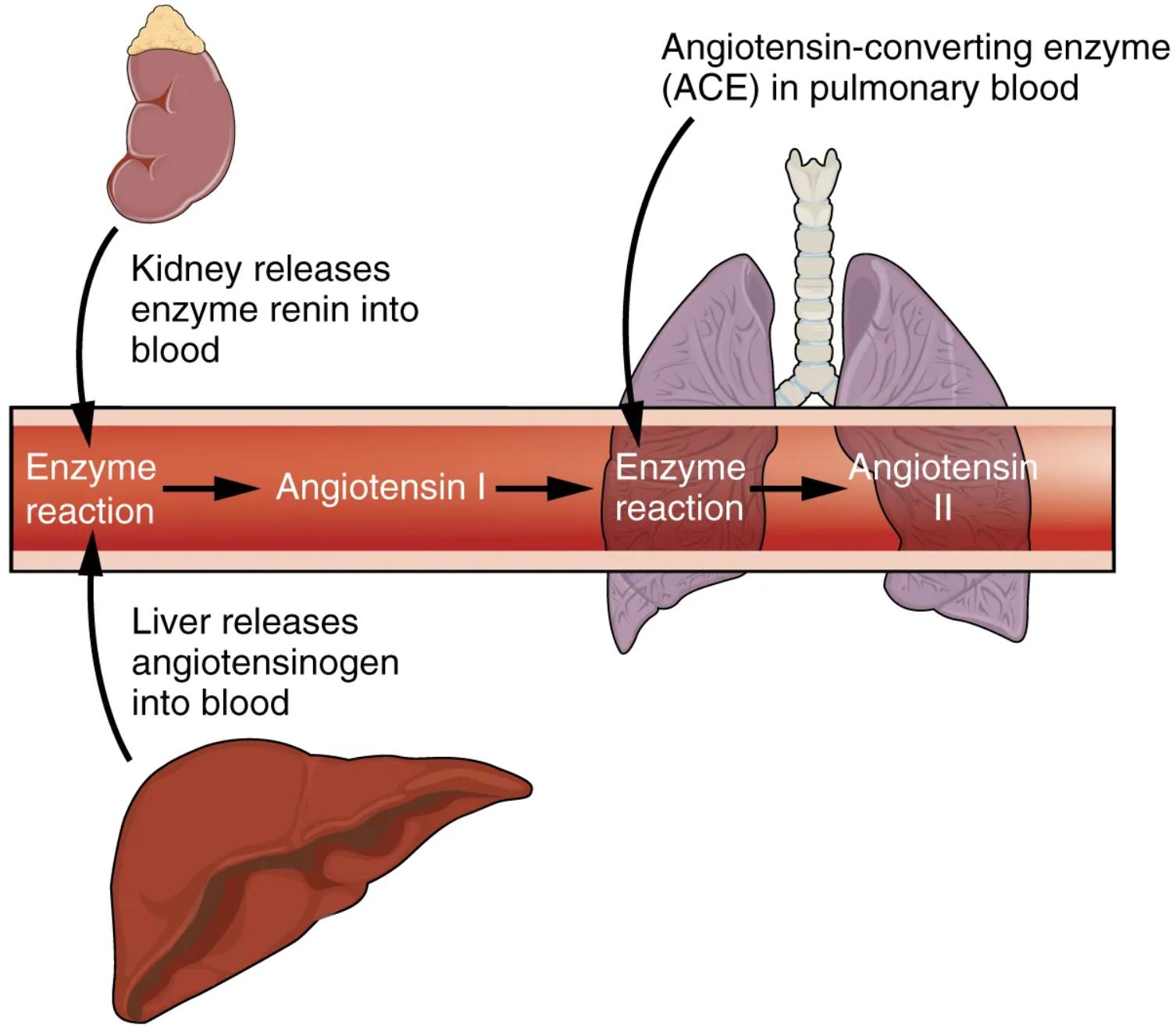

The maintenance of stable blood pressure and fluid balance is a critical physiological imperative, largely governed by a powerful hormonal system known as the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS). This article focuses on the initial, pivotal steps of this cascade: the enzyme renin converting the pro-enzyme angiotensin I and its subsequent transformation into active angiotensin II. Understanding this fundamental sequence, involving the kidneys, liver, and lungs, is essential for comprehending the body’s response to low blood pressure and the pathophysiology of hypertension.

Kidney releases enzyme renin into blood: The kidney, specifically the juxtaglomerular cells within its cortex, is the primary source of renin. Renin secretion is triggered by factors such as low blood pressure, decreased sodium delivery to the macula densa, or sympathetic nerve activity.

Liver releases angiotensinogen into blood: The liver continuously synthesizes and releases angiotensinogen, a glycoprotein, into the bloodstream. Angiotensinogen is an inactive precursor protein, serving as the substrate for renin.

Enzyme reaction (Angiotensin I): This refers to the biochemical conversion of angiotensinogen into angiotensin I. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme renin, cleaving a specific peptide bond in angiotensinogen. Angiotensin I itself has little biological activity but is a crucial intermediate.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) in pulmonary blood: ACE is an enzyme predominantly found on the surface of endothelial cells, particularly abundant in the capillaries of the lungs. Its role is to convert angiotensin I into the biologically active hormone angiotensin II.

Enzyme reaction (Angiotensin II): This represents the conversion of inactive angiotensin I into the potent octapeptide angiotensin II, catalyzed by ACE. Angiotensin II is the main effector molecule of the RAAS, mediating most of its physiological effects on blood pressure and fluid balance.

The Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) is one of the most vital hormonal systems in the body, primarily responsible for regulating arterial blood pressure, extracellular fluid volume, and systemic vascular resistance. It is typically activated in response to conditions that threaten the body’s fluid status or blood pressure, such as hemorrhage or dehydration. This complex cascade involves a coordinated effort between several organs—the kidneys, liver, and lungs—each contributing a crucial component to the intricate pathway. The image clearly illustrates the initial steps of this system, highlighting the key players and their roles in initiating the powerful physiological responses.

The intricate cascade begins in the kidneys, which act as the primary sensors for blood pressure and fluid status. When the juxtaglomerular cells in the kidney detect a decrease in renal perfusion pressure (low blood flow to the kidney), a reduction in sodium chloride delivery to the macula densa, or receive sympathetic stimulation, they respond by secreting the enzyme renin directly into the bloodstream. Concurrently, the liver continually synthesizes and releases angiotensinogen, an alpha-2 globulin protein, into the circulation. This angiotensinogen serves as the foundational precursor for the entire RAAS pathway, ready to be acted upon by renin.

Once renin enters the bloodstream, it acts as a highly specific protease, cleaving a decapeptide from the N-terminus of angiotensinogen. This enzymatic reaction results in the formation of angiotensin I, a relatively inactive decapeptide. Angiotensin I then travels through the circulation until it reaches the capillaries of the lungs, where it encounters another crucial enzyme: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE). ACE, found abundantly on the endothelial cells lining the pulmonary capillaries, rapidly converts angiotensin I into the biologically potent octapeptide, angiotensin II. This conversion is a critical step, as angiotensin II is the primary active hormone of the RAAS, orchestrating a wide range of physiological responses aimed at restoring blood pressure and fluid volume.

Dysregulation of this initial phase of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System is a significant factor in the development and progression of various cardiovascular diseases, most notably hypertension. Overproduction or inappropriate activation of renin can lead to elevated levels of angiotensin II, resulting in chronic vasoconstriction and sustained high blood pressure. This continuous activation places undue strain on the cardiovascular system, increasing the risk of heart attack, stroke, and kidney damage. Pharmacological interventions targeting this pathway, such as ACE inhibitors (which block the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II) and direct renin inhibitors (which prevent renin from acting on angiotensinogen), are cornerstones in the treatment of hypertension and related conditions, underscoring the profound clinical importance of understanding these initial enzymatic reactions.