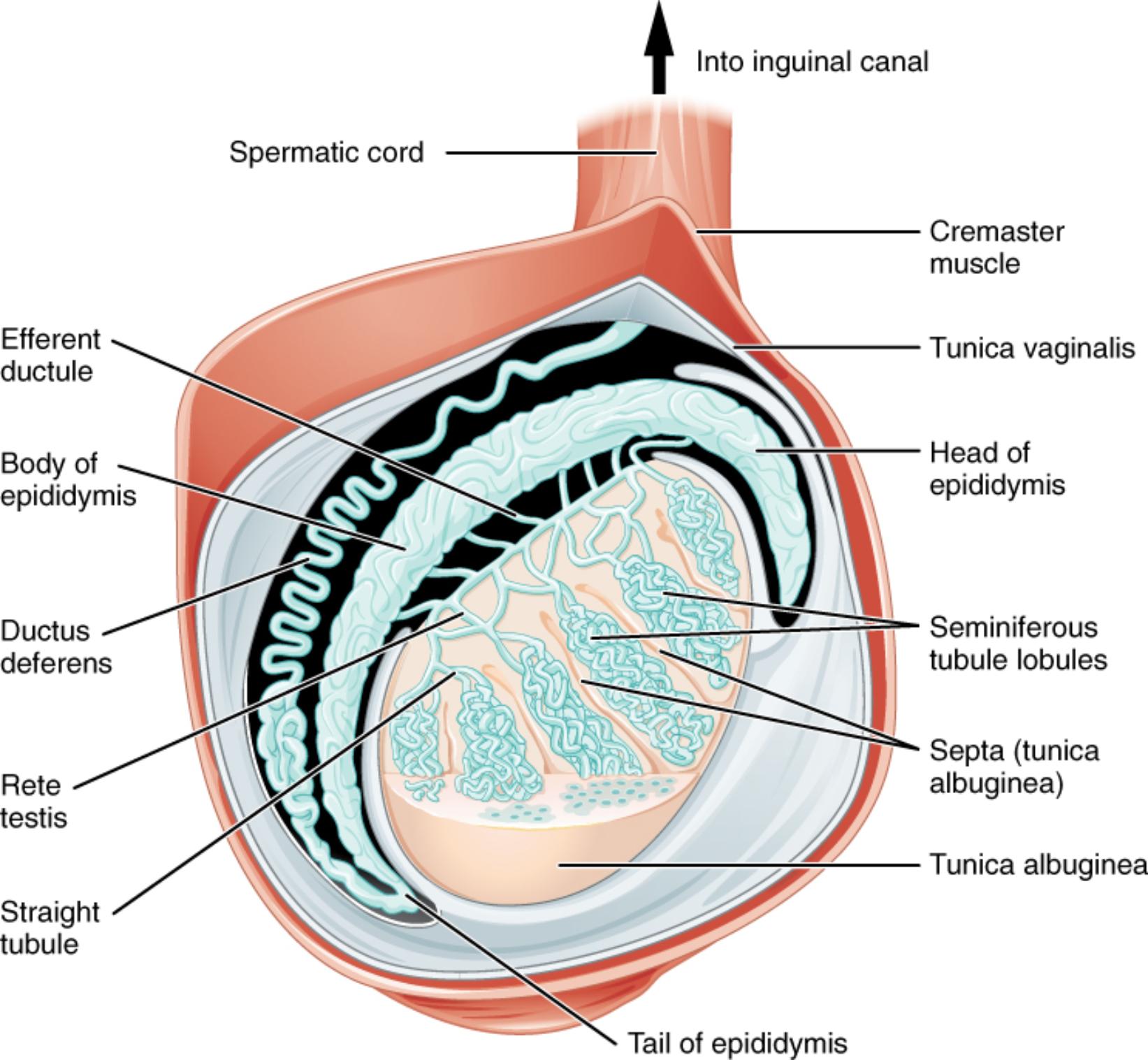

The testis is the primary male reproductive organ, a complex structure meticulously organized for the continuous production and maturation of sperm. This sectional view diagram offers an unparalleled glimpse into the internal architecture of the testis and its intimately associated epididymis, highlighting the precise pathways that sperm traverse from their site of creation to their storage and final preparation for ejaculation. Understanding this microanatomy is fundamental to comprehending the intricate processes of spermatogenesis, sperm maturation, and the overall functionality of the male reproductive system.

Dissecting the Internal Anatomy of the Testis and Epididymis

Into inguinal canal: This arrow indicates the upward direction of structures, specifically the spermatic cord, as they ascend from the scrotum towards the inguinal canal in the abdominal wall. The inguinal canal provides a passage for the spermatic cord into the abdominal cavity.

Spermatic cord: A cord-like structure in the male that extends from the abdomen into the scrotum. It contains the ductus deferens, testicular artery, pampiniform plexus of veins, nerves, and lymphatic vessels, all bundled together.

Cremaster muscle: Striated skeletal muscles located within the spermatic cord and surrounding the testes. They are responsible for elevating the testes closer to the body in response to cold temperatures or sexual arousal, a reflex known as the cremasteric reflex.

Tunica vaginalis: A two-layered serous membrane that partially covers the testis. It is derived from the peritoneum during testicular descent and forms a fluid-filled cavity, allowing the testis to move freely within the scrotum.

Head of epididymis: The uppermost and largest part of the epididymis, located superior to the testis. This region receives immature sperm from the efferent ductules and is the initial site of sperm concentration and maturation.

Seminiferous tubule lobules: The testes are divided into numerous lobules by septa, and within each lobule are one to four highly convoluted seminiferous tubules. These are the primary sites of spermatogenesis, where sperm are continuously produced.

Septa (tunica albuginea): Fibrous partitions that extend inward from the tunica albuginea, dividing the testis into approximately 250-300 lobules. These septa provide structural support and compartmentalize the seminiferous tubules.

Tunica albuginea: A tough, fibrous, white connective tissue capsule that directly surrounds and protects the testis. It lies deep to the tunica vaginalis and gives the testis its characteristic shape.

Tail of epididymis: The narrow, inferior portion of the epididymis, located along the posterior aspect of the testis. This is the primary site for the storage of mature sperm before ejaculation.

Efferent ductule: A series of small ducts that emerge from the rete testis and connect to the head of the epididymis. These ductules transport immature sperm from the testis to the epididymis.

Body of epididymis: The middle, narrower portion of the epididymis, situated between the head and the tail. Sperm continue their maturation process as they pass through this region.

Ductus deferens: A muscular tube that transports mature sperm from the epididymis to the ejaculatory duct. It is a key component of the spermatic cord and contracts forcefully during ejaculation to propel sperm.

Rete testis: A network of tiny tubules located in the mediastinum testis, a connective tissue region in the posterior testis. It collects sperm from the straight tubules and channels them into the efferent ductules.

Straight tubule: Short, straight tubules that connect the seminiferous tubules to the rete testis. They act as a conduit for newly formed sperm from the site of production to the collection network.

The Testis: A Factory for Male Gametes

The testis, a paired organ encased within the scrotum, is the epicenter of male reproductive function, serving as the primary site for spermatogenesis—the continuous production of sperm. This sectional view diagram meticulously illustrates the intricate internal architecture that facilitates this vital process, from the initial formation of sperm to their crucial maturation phase. Understanding this detailed anatomy is foundational to grasping the complexities of male fertility.

The internal structure of the testis is highly organized, beginning with its protective outer layers. The tunica albuginea, a dense fibrous capsule, directly envelops the testicular tissue, providing structural integrity. From this capsule, fibrous septa extend inward, dividing the testis into numerous lobules. Each lobule houses one to four highly convoluted seminiferous tubules, which are the actual sites where spermatogenesis occurs. Within these tubules, germ cells undergo mitosis and meiosis, transforming into spermatozoa, the male gametes.

Once formed, the immature sperm embark on a journey through a specialized duct system within the testis before reaching the epididymis. From the seminiferous tubules, sperm pass into short straight tubules, which then converge into the rete testis—a network of interconnected channels. From the rete testis, a series of efferent ductules emerge, connecting the testis to the head of the epididymis. It is within the epididymis, a comma-shaped structure intimately associated with the posterior aspect of the testis, that sperm undergo their final stages of maturation, acquiring motility and the capacity to fertilize an ovum. The epididymis is divided into a head, body, and tail, with the tail serving as the primary storage site for mature sperm. During ejaculation, these mature sperm are forcefully expelled from the tail of the epididymis into the ductus deferens, which then ascends into the spermatic cord.

Unraveling the Microanatomy of Sperm Production and Maturation

The testis is arguably the most vital organ of the male reproductive system, a dynamic factory meticulously designed for the continuous production of male gametes. This sectional view provides an in-depth look at its internal organization, highlighting the specialized structures involved in spermatogenesis and the subsequent maturation and transport of sperm. A detailed understanding of this microanatomy is fundamental for appreciating the biological mechanisms underlying male fertility and the pathophysiology of related disorders.

At the core of testicular function are the seminiferous tubule lobules, which are the sites of active sperm production. The testis is enveloped by a tough, white, fibrous capsule known as the tunica albuginea. From this capsule, fibrous septa extend inward, dividing the testicular tissue into approximately 250-300 lobules. Each lobule contains one to four highly convoluted seminiferous tubules, where germ cells undergo a complex process of mitosis, meiosis, and spermiogenesis to transform into mature spermatozoa. This process is supported by Sertoli cells within the tubules and regulated by Leydig cells (interstitial cells) located between the tubules, which produce testosterone.

Once formed within the seminiferous tubules, the newly created, non-motile sperm are transported through a precise series of ducts. They first move into short, straight tubules, which then lead into the rete testis, a network of anastomosing channels situated in the mediastinum testis. From the rete testis, sperm are collected by 15-20 efferent ductules. These efferent ductules pierce the tunica albuginea and converge to form the head of the epididymis. The epididymis is a comma-shaped, highly coiled tube located along the posterior aspect of the testis, divided into a head, body, and tail. It is within the epididymis that sperm undergo their crucial post-testicular maturation, acquiring both motility and the capacity to fertilize an ovum. This maturation process can take several days to weeks.

The tail of the epididymis serves as the primary storage site for mature sperm. During sexual arousal and ejaculation, these mature sperm are propelled by smooth muscle contractions into the ductus deferens (vas deferens). The ductus deferens then ascends as part of the spermatic cord, which also contains the testicular artery, the pampiniform plexus of veins (important for cooling blood to the testis), autonomic nerves, and lymphatic vessels. The spermatic cord travels through the inguinal canal, eventually leading the sperm towards the ejaculatory duct and ultimately the urethra for expulsion. This entire pathway, from the seminiferous tubules to the ductus deferens, ensures the efficient production, maturation, and transport of male gametes.

Conclusion

This detailed sectional view of the testis and epididymis provides an invaluable insight into the highly organized microanatomy that underpins male reproductive function. By illuminating the seminiferous tubules as the site of sperm production, and tracing the intricate pathway through the rete testis, efferent ductules, and the epididymis for maturation and storage, the diagram clarifies the sophisticated processes involved. A thorough understanding of these structures and their coordinated roles is essential for comprehending male fertility, hormonal regulation, and the diagnosis and treatment of conditions affecting sperm production and transport.