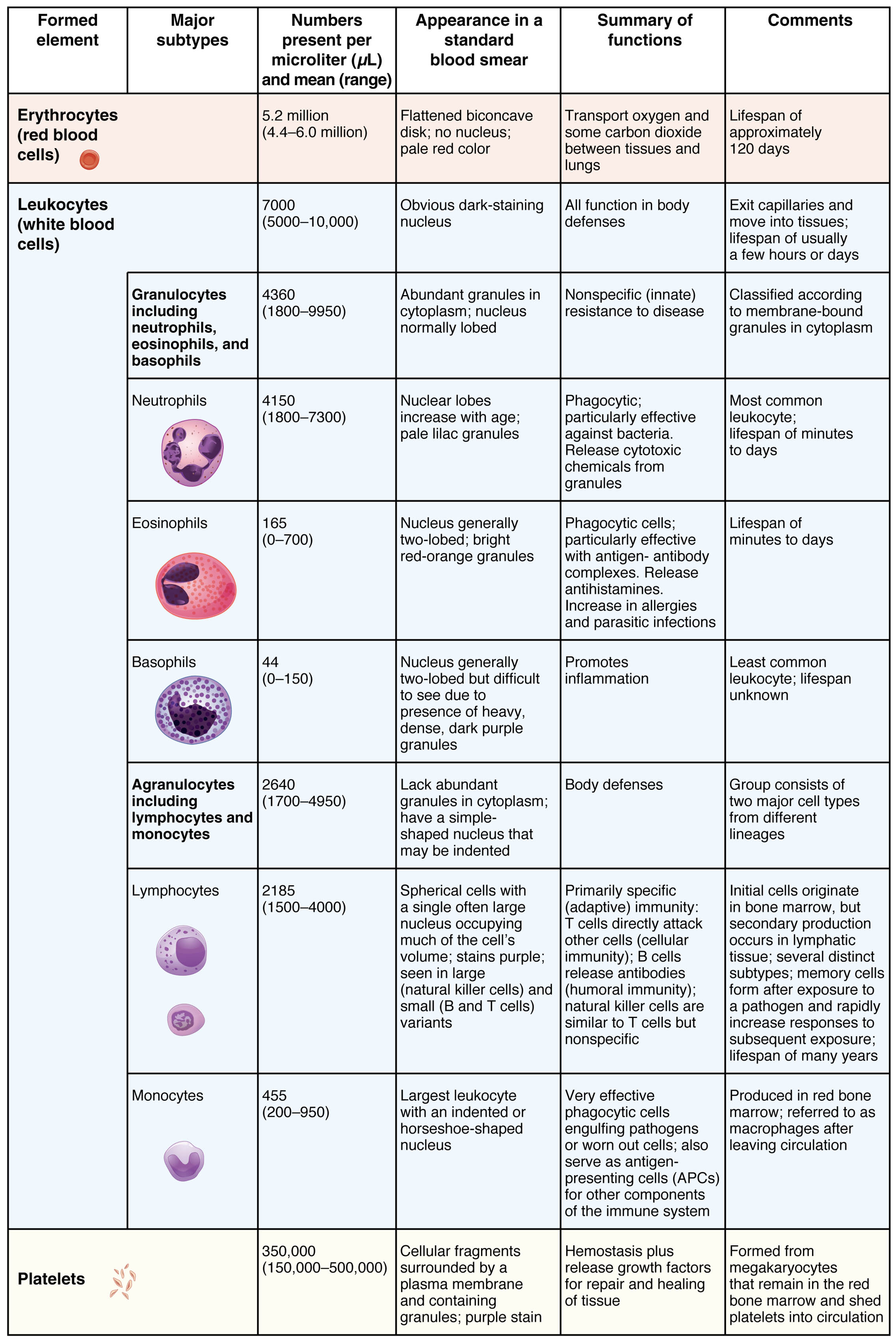

Blood is a complex fluid that sustains life by transporting oxygen, defending against pathogens, and facilitating clotting, with its formed elements playing a central role in these functions. This chart provides a detailed overview of the major subtypes of formed elements—erythrocytes, leukocytes, and platelets—along with their numbers, appearance, functions, and clinical notes. Delving into this information enhances appreciation of how these cellular components maintain bodily homeostasis and respond to physiological challenges.

Key Components of Formed Elements in Blood

The chart categorizes blood’s formed elements, offering insights into their structure and role.

Erythrocytes (red blood cells):

Erythrocytes are the most abundant cells in blood, responsible for oxygen and carbon dioxide transport between tissues and lungs. Their flattened, biconcave, disc-like shape without nuclei maximizes surface area for hemoglobin binding, with a lifespan of approximately 120 days.

Leukocytes (white blood cells):

Leukocytes are critical for body defense, present in lower numbers than erythrocytes, and exhibit obvious dark-staining nuclei on smears. They exit capillaries to move into tissues, with a lifespan ranging from hours to days depending on subtype and activation.

Granulocytes (including neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils):

Granulocytes are a subset of leukocytes with abundant granules in their cytoplasm, numbering 4360-9950 per microliter, and provide nonspecific resistance to disease. Their classification is based on membrane-bound granules, which vary in appearance and function.

Neutrophils:

Neutrophils, the most common leukocytes at 4150-7300 per microliter, feature nuclei with multiple lobes and pale lilac granules, making them highly phagocytic. They release cytotoxic chemicals from granules to combat bacterial infections, with a short lifespan of minutes to hours.

Eosinophils:

Eosinophils, numbering 165-700 per microliter, have nuclei with two lobes and bright red-orange granules, playing a key role in phagocytic activity against antigens. They release antihistamines and increase in allergic or parasitic infections, with a lifespan of days.

Basophils:

Basophils, the least common at 44-150 per microliter, possess nuclei with two lobes but dense, dark purple granules that obscure them, promoting inflammation. Their exact lifespan remains unknown, though they are critical in allergic responses.

Agranulocytes (including lymphocytes and monocytes):

Agranulocytes lack abundant granules, numbering 2640-4950 per microliter, and have a simple cytoplasm with shaped nuclei, contributing to body defenses. This group consists of two major cell types from distinct lineages, supporting both innate and adaptive immunity.

Lymphocytes:

Lymphocytes, at 2185-4000 per microliter, feature a single large nucleus occupying much of the cell’s volume, staining purple, and are primarily specific (adaptive) immunity cells. They include T cells (cellular immunity), B cells (humoral immunity), and natural killer cells, with lifespans ranging from years to many years.

Monocytes:

Monocytes, numbering 455-950 per microliter, are the largest leukocytes with an indented or horseshoe-shaped nucleus, acting as phagocytic cells. They engulf pathogens or worn-out cells, presenting antigens (APCs) for immune system components, and mature into macrophages after leaving circulation.

Platelets:

Platelets, at 350,000 (150,000-500,000) per microliter, are cellular fragments from megakaryocytes with purple-staining granules, essential for hemostasis. They release growth factors for tissue repair and healing, formed in the red bone marrow and shed into circulation.

The Anatomical and Physiological Role of Formed Elements

Formed elements are the cellular components of blood, each with specialized roles that sustain life and protect against threats. Erythrocytes rely on hemoglobin, an iron-containing protein, to bind oxygen in the lungs and release it in tissues, influenced by pH and carbon dioxide levels via the Bohr effect. Leukocytes, including granulocytes and agranulocytes, form the immune system’s frontline, with neutrophils responding rapidly to bacterial invasions and lymphocytes providing long-term immunity through antibody production.

Granulocytes’ cytoplasmic granules contain enzymes and mediators; for instance, eosinophils release major basic protein against parasites, while basophils liberate histamine during allergic reactions. Agranulocytes like monocytes differentiate into macrophages or dendritic cells, presenting antigens to T cells, which orchestrate immune responses. Platelets initiate clotting by adhering to damaged endothelium, releasing factors like thromboxane A2 to amplify the process.

- Oxygen Transport: Erythrocytes’ biconcave shape increases flexibility for capillary passage; hemoglobin also buffers blood pH.

- Immune Defense: Neutrophils dominate acute infections; lymphocytes’ memory cells enable faster responses to re-exposure.

- Clotting Mechanism: Platelets aggregate within seconds of injury; their granules store serotonin to constrict vessels.

Physical Characteristics and Clinical Relevance

The physical appearance of formed elements, as depicted in the chart, aids in microscopic identification and clinical assessment. Erythrocytes’ pale red color reflects their hemoglobin content, while leukocytes’ dark nuclei and granule variations distinguish subtypes under a standard smear.

Clinically, these characteristics guide diagnosis and treatment. Low erythrocyte counts may indicate anemia, prompting hemoglobin electrophoresis to detect thalassemia or sickle cell disease. Elevated neutrophils suggest bacterial infection, while increased eosinophils point to parasitic or allergic conditions. Platelet counts below 150,000 per microliter signal thrombocytopenia, requiring bone marrow evaluation or transfusion.

- Diagnostic Techniques: Complete blood count (CBC) quantifies cell numbers; differential smears assess morphology.

- Therapeutic Interventions: Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) boosts neutrophil levels; iron supplements correct microcytic anemia.

Conclusion

The chart of formed elements in blood offers a window into the intricate cellular machinery that sustains life, from oxygen delivery to immune protection and clot formation. Each subtype, with its unique appearance and function, reflects the body’s ability to adapt to diverse physiological demands and challenges. By understanding these components, one can better appreciate the diagnostic tools and treatments that maintain health, underscoring the importance of regular blood analysis in clinical practice.