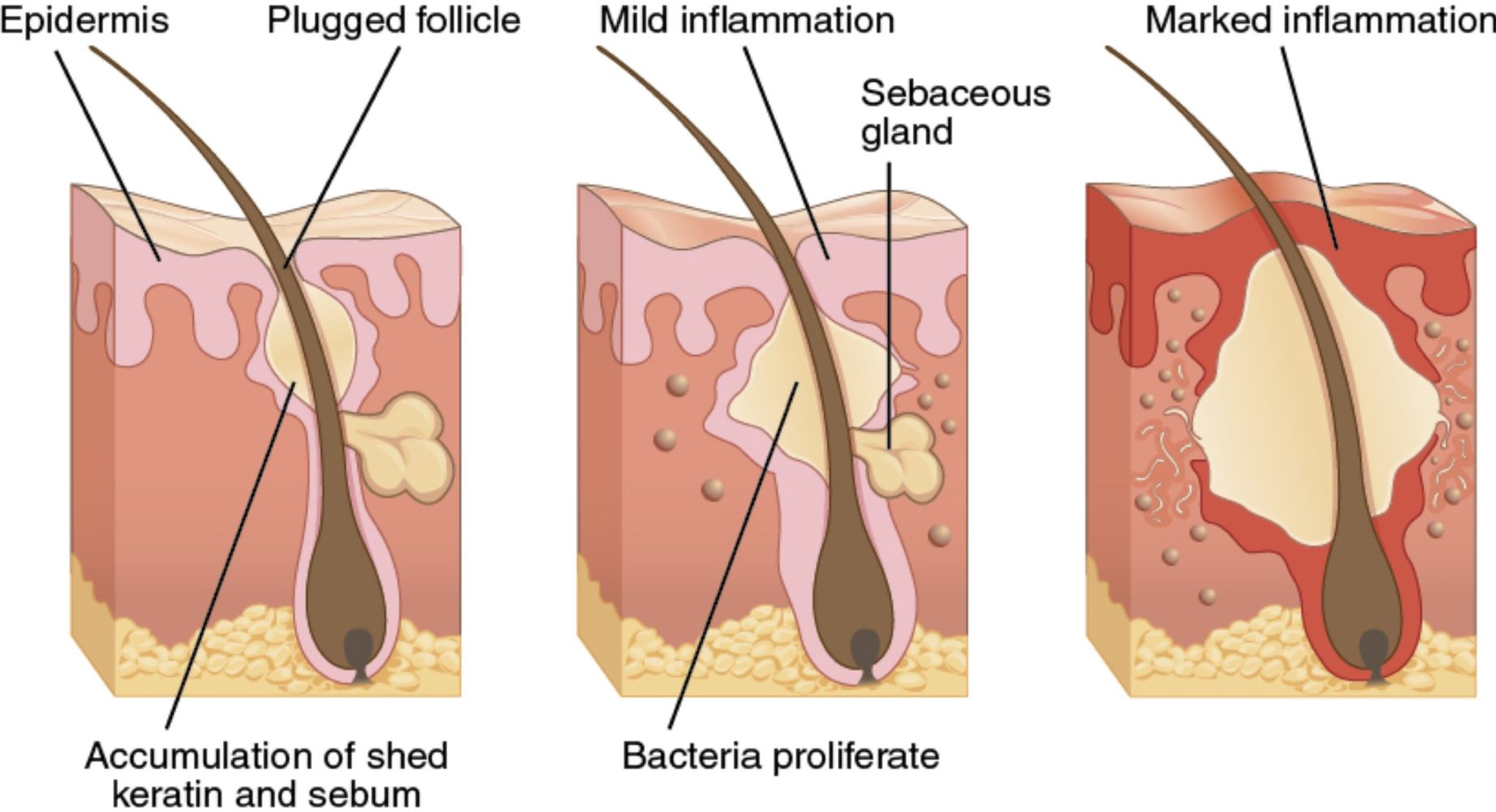

Acne is a common skin condition driven by overactive sebaceous glands, leading to blackheads and inflammation, as illustrated in this detailed sectional view of the skin. This article explores the anatomical progression of acne, its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options, providing a comprehensive guide for understanding and managing this widespread dermatological issue.

Image Analysis: Sectional View of Acne Development

Epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin, shown in the diagram as the topmost layer where the hair shaft emerges. It serves as a protective barrier but can become involved in acne when dead skin cells fail to shed properly, contributing to follicle blockage.

Plugged Follicle

This label highlights the initial stage of acne where the hair follicle becomes clogged with an accumulation of shed keratin and sebum, as depicted in the first panel. This blockage creates an environment conducive to bacterial growth and inflammation, setting the stage for acne formation.

Sebaceous Gland

The sebaceous gland, shown attached to the hair follicle, produces sebum, an oily substance that lubricates the skin and hair, as seen in the second panel. Overproduction of sebum, often due to hormonal changes, contributes to the clogging of the follicle and exacerbates acne development.

Accumulation of Shed Keratin and Sebum

This label, in the first panel, indicates the buildup of dead skin cells (keratin) and sebum within the follicle, leading to the formation of a comedo, such as a blackhead or whitehead. This accumulation is a primary factor in the early stages of acne, creating a plug that traps bacteria and oil inside the follicle.

Bacteria Proliferate

In the second panel, this label shows the proliferation of bacteria, particularly Cutibacterium acnes (formerly Propionibacterium acnes), within the plugged follicle. The bacterial growth triggers an immune response, leading to inflammation and the progression of acne to more severe forms like papules or pustules.

Mild Inflammation

This label, also in the second panel, illustrates the early inflammatory response as the body reacts to the bacterial proliferation and sebum buildup. The surrounding tissue becomes red and slightly swollen, indicating the beginning of an acne lesion such as a pimple.

Marked Inflammation

In the third panel, this label shows a more advanced stage where inflammation has intensified, resulting in a larger, redder, and more swollen area around the follicle. This stage often corresponds to the development of more severe acne forms, such as nodules or cysts, which can be painful and lead to scarring.

What Is Acne? A Common Skin Condition Explained

Acne is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that affects the pilosebaceous unit, which includes the hair follicle and its associated sebaceous gland. It is one of the most prevalent dermatological conditions worldwide, impacting individuals across all age groups, though it is most common during adolescence due to hormonal fluctuations.

- Acne typically presents as blackheads, whiteheads, pimples, or cysts, often on the face, back, chest, and shoulders.

- The condition arises from a combination of factors, including excess sebum production, clogged follicles, bacterial growth, and inflammation.

- While not life-threatening, acne can significantly affect quality of life, leading to emotional distress and potential scarring if untreated.

- Understanding its anatomical progression, as shown in the sectional view, is key to effective management and treatment.

Causes and Risk Factors of Acne

Acne develops due to a complex interplay of physiological and environmental factors that disrupt the normal function of the pilosebaceous unit.

- Hormonal Changes: Increased androgen levels, particularly during puberty, stimulate the sebaceous glands to produce more sebum, a primary driver of acne.

- Genetic Predisposition: A family history of acne increases the likelihood of developing the condition, with genetic factors influencing sebum production and skin cell turnover.

- Bacterial Growth: Cutibacterium acnes thrives in the oxygen-poor environment of a plugged follicle, triggering an inflammatory response as shown in the diagram.

- Dietary Factors: High-glycemic foods (e.g., sugary snacks) and dairy products may exacerbate acne by increasing insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which boosts sebum production.

- Stress: Psychological stress can elevate cortisol levels, which in turn stimulate sebum production and worsen acne flares.

- Medications: Certain drugs, such as corticosteroids or lithium, can induce or aggravate acne as a side effect by altering skin physiology.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Acne

Acne manifests in various forms, ranging from mild comedones to severe cystic lesions, with symptoms depending on the stage and severity of the condition.

- Comedones: Blackheads (open comedones) and whiteheads (closed comedones) form due to plugged follicles, as depicted in the first panel of the image.

- Inflammatory Lesions: Papules, pustules, and nodules arise as inflammation progresses, with redness and swelling becoming more pronounced, as shown in the second and third panels.

- Cysts: Severe acne can lead to painful, fluid-filled cysts beneath the skin, often resulting in scarring if untreated.

- Scarring: Chronic or severe acne can cause permanent scars, such as atrophic (depressed) or hypertrophic (raised) scars, particularly in cases of marked inflammation.

- Acne commonly affects areas rich in sebaceous glands, including the face, back, chest, and shoulders, and may be accompanied by tenderness or discomfort.

Diagnosis of Acne: Identifying the Condition

Diagnosing acne is typically straightforward, relying on a clinical examination of the skin to assess the type and severity of lesions.

- A clinical assessment by a dermatologist focuses on identifying the types of lesions (e.g., comedones, pustules, cysts) and their distribution on the body.

- The severity is often graded using scales like the Global Acne Grading System (GAGS), which considers the number, type, and location of lesions.

- In cases of suspected hormonal acne, blood tests may be ordered to evaluate levels of androgens or other hormones like testosterone or DHEA-S.

- A detailed history is taken to identify potential triggers, such as diet, stress, or medications, that may be contributing to the condition.

Treatment Options for Acne: Managing Symptoms and Preventing Scarring

Treatment for acne aims to reduce sebum production, unclog follicles, kill bacteria, and decrease inflammation, with options varying based on severity.

- Topical Retinoids: Medications like tretinoin or adapalene unclog follicles and promote skin cell turnover, addressing the initial plugging seen in the first panel.

- Benzoyl Peroxide: This kills Cutibacterium acnes and reduces inflammation, targeting the bacterial proliferation shown in the second panel.

- Topical Antibiotics: Clindamycin or erythromycin can be applied to reduce bacterial growth and inflammation in{THE} inflammation, particularly for moderate to severe acne.

- Oral Antibiotics: Tetracyclines (e.g., doxycycline) are used for moderate to severe acne to control bacterial growth and inflammation.

- Hormonal Therapy: For women, oral contraceptives or spironolactone can help regulate hormone levels and reduce sebum production.

- Isotretinoin: A powerful oral retinoid, isotretinoin is reserved for severe, scarring acne, addressing all aspects of acne pathogenesis but requiring careful monitoring.

Prevention Strategies for Acne

Preventing acne involves adopting a consistent skincare routine and avoiding triggers that exacerbate the condition.

- Gentle Cleansing: Washing the skin twice daily with a mild, non-comedogenic cleanser helps remove excess oil and prevent follicle clogging.

- Using non-comedogenic skincare and makeup products reduces the risk of pore blockage, a key factor in acne development.

- Avoiding picking or squeezing acne lesions prevents worsening inflammation and reduces the risk of scarring.

- Managing stress through relaxation techniques like meditation can help lower cortisol levels, which may otherwise trigger sebum production.

Complications of Acne: Addressing Potential Risks

Untreated or improperly managed acne can lead to both physical and emotional complications, particularly in severe cases.

- Scarring: Persistent inflammation, as shown in the third panel, can lead to permanent atrophic or hypertrophic scars, which may require advanced treatments like laser therapy.

- Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation: Dark spots may remain after acne heals, particularly in darker skin tones, due to excess melanin production during inflammation.

- Severe acne can lead to emotional distress, including anxiety or depression, due to its impact on appearance and self-esteem.

- In rare cases, cystic acne can become infected, leading to abscess formation, which may require drainage and antibiotics.

Living with Acne: Emotional and Practical Considerations

Acne can have a significant impact on emotional well-being, particularly for those with visible or severe lesions that affect their appearance.

- Patients may experience self-consciousness or embarrassment, especially during adolescence when acne is most common and social pressures are high.

- Support from healthcare providers, family, or peers can help individuals cope with the psychological effects of acne and build confidence.

- Adopting a consistent treatment plan and avoiding triggers empowers patients to manage their symptoms effectively.

- Education about acne’s treatability can reduce stigma and encourage individuals to seek timely care, improving outcomes.

Acne, while a challenging condition, can be effectively managed with a combination of medical treatments, lifestyle adjustments, and emotional support. By understanding its anatomical basis, as depicted in the sectional view, and addressing its underlying causes, individuals can achieve clearer skin and improved quality of life.